The article “Archaeologists May Have Found 2,500-year-old Persian Military Base in Northern Israel” written by Phillipe Bohstrom was originally published on December 23, 2018 in Haaretz. Excepting images that appear in the original Haaretz publication, all other images and accompanying captions are unique to the version printed below (and do not appear in Haaretz). Kindly noted that version printed below has been edited.

========================================================================================

Around 2,500 years ago, the Achaemenid king Cambyses II (r. 530 to 522 BCE) mounted an all-out assault on Egypt, basing the campaign in Palestine. Now archaeologists believe they may have found a camp in northern Israel from which the Achaemenid emperor launched his invasion of the Nile Kingdom.

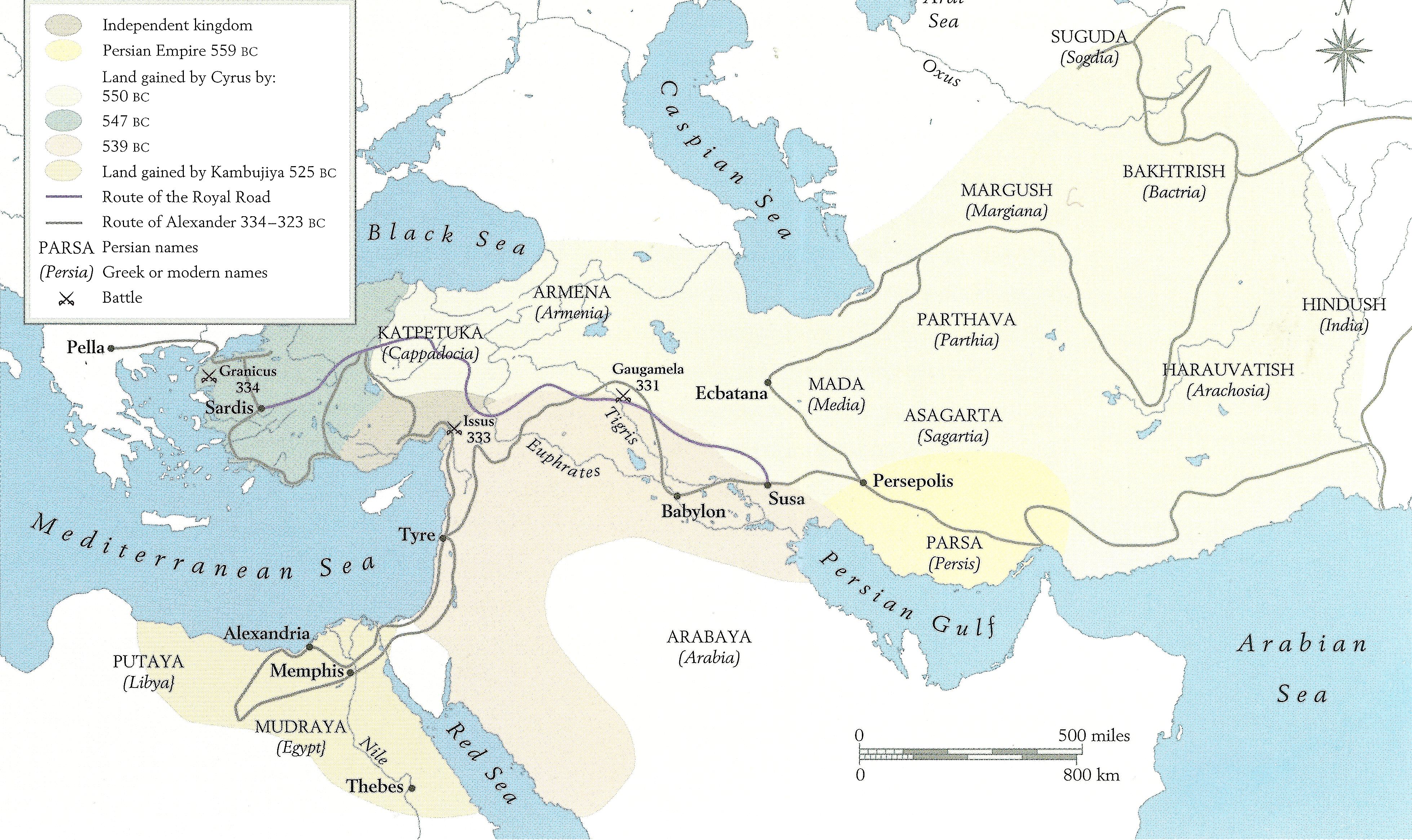

The Achaemenid Empire had been founded by Cyrus the Great (having united the Medes and the Persians) in the 580s BCE, overcoming the Lydian and Neo-Babylonian empires as it expanded. Cambyses was his son.

A map of the Achaemenid Empire drafted by Kaveh Farrokh on page 87 (2007) of the book Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا-:

Among the findings at Tel Keisan, a hill rising 28 meters from the coastal plain near the city of Acre (aka Akko) in northern Israel, were ruins dated to the Persian period by ceramic jars and cooking pots in Greek and Phoenician styles typical of that time.

The Phoenicians on the Palestine coast and their fleet had been subjugated by the Assyrians and then by the Persians; and the ancient Greek historian Herodotus said that Greek mercenaries fought in the Persian emperor Cambyses’ army. The Greek and Phoenician ceramic finds in the Persian layer of Tel Keisan suggest that this area was part of the base camp of the great Achaemenid campaign. As noted by Prof. Gunnar Lehmann of Ben-Gurion University, who has been codirecting the Tel Keisan excavation:

“Under Cambyses, the Persians wanted to prepare for war with and conquest of Egypt. They did that in Palestine”.

Reconstruction in 1971 of elite Achaemenid army infantryman (Source: Ancient Origins).

It was on the Acre plain that Cambyses assembled his army that would sweep down to Egypt, in the 520s BCE. The excavations at Tel Keisan are being carried out by Lehmann and David Schloen from the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. In the two seasons of excavations, in 2016 and 2018, the archaeologists exposed levels dating to the Hellenistic period (3rd and 2nd century BCE), the Persian period (5th-4th centuries B.C.E.) and the Iron Age IIC (7th century BCE). The archaeologists have also found earlier levels, dating to the Late Iron Age IIA around 3,000 years old, but these have yet to be thoroughly explored.

Tell Keisan means “hill of treachery” in Arabic, though why it got that name is no longer known. Mentioned from the 12th century onward by Arabic chroniclers, it presumably refers to an embarrassing military event now forgotten. Nor is the settlement’s name in antiquity known.

Tell Keisan (Source: Ivgeni Ostrovski – Haaretz). The Persian camp on the Acre plain seems to have been a base camp for King Cambyses’ all-out attack on Egypt in the 520s BCE.

Basket handle cases

Keisan sits on an imposing hill rising 28 meters above the ground in the heart of the Acre plain. The site, which has been occupied for at least 6,000 years, is strategically positioned overlooking the approach to the fertile Plain of Jezreel (Esdraelon), as well as commercial trade routes between the Galilee, the Jordan Valley, and other points to the east.

Previous surveys and excavations have exposed massive systems of fortifications from the Iron Age II, around 1,000 to 587 BCE, on the Acre plain.

Based on the archaeological layers, it seems that the serial conquerors of Palestine found the settlement’s strategic location irresistible: the locals, the Egyptians, the Assyrians, and the Persians under Cambyses II, who seem to have used it as their administrative center and military base of operations in the 5th century BCE, and later as well.

Keisan was one of several Egyptian strongholds along the Acre coastal plain during the time they controlled Palestine, from around 637 to 605 BCE, says Lehmann. Two other known ones were at Achziv and Tel Kabri, and there may have been more.

Jar found at Tel Keisan (Source: Ivgeni Ostrovski – Haaretz).

At Keisan itself, immediately beneath the Persian level, the archaeologists exposed a large building with storage rooms dating to the earlier Egyptian empire of the 26th Dynasty. The building apparently began its career in the 7th century B.C.E. and seems to have served as a governmental or administrative building, which among other things provided food for its personnel.

The building also contained Phoenician, Cypriot and East Greek pottery, but of an earlier type, typical of that pre-Persian time. The storage rooms contained numerous complete storage jars, mostly of Phoenician origin, and also also Cypriot “basket-handle” amphoras typical of the 7th century BCE. Among the people using the facility may have been Greek mercenaries serving under Egyptian command since the pottery included Greek cooking pots.

Cambyses assembles the Achaemenid Army

Under the Persians, the Mediterranean coastal city of Acre expanded to encompass the settlement at Keisan as well, and the peninsula that forms the northern end of the Bay of Haifa, with its ancient harbor Tell Abu Hawam.

Cambyses II’s campaign to conquer Egypt, assembling forces to “cross the waterless deserts” apparently in 525 BCE was described by Herodotus. Cambyses II thrashed Pharaoh Psamtik III at Memphis, and won “Egypt and the sea” (Herodotus 3.34) Consequently, Cambyses II became the first Persian king to rule ancient Egypt.

Scholars cite two other ancient sources aside from Herodotus that locate Cambyses II’s army and fleet in the Acre plain in the 520s B.C.E. The first is another Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus, when telling of the preparations made in 374 B.C.E. by the Persian monarch Ataxerxes II towards subordinating Egypt:

“The Perisan army gathered at the city of Ake, numbering two hundred thousand barbarians led by Pharnabazus, and twenty thousand Greek mercenaries under the command of Iphicrates. Of the fleet, the triremes numbered three hundred and the thirty-oared ships two hundred. And great was the number of those carrying food and other supplies” – Diodurus Siculus, Bibliotheke 15.41.3 (Translated by Peter Green, 2010)

The second source is the Greek geographer and philosopher Strabo:

“Then follows Ptolemais, a large city, formerly called Ace. It was the place for rendezvous for the Persians in their expedition against Egypt” – Strabo Geography 16.2.25-27 (Translation by H. C. Hamilton and W. Falconer, 2010)

These sources, combined with Herodotus, suggest that Artaxerxes was not the first to have used the Akko plain to launch a campaign against Egypt, which lies to the southwest of Israel, then Palestine. In fact, it seems that from the 520s B.C.E. onwards, that several sites along the Palestine coast – Tell al-Fuhkhar (Acre itself), Tell Keisan, Tell Kurdana (Tel Aphek), and Tell Abu Hawam (Haifa) were used for anchoring the fleet and as a rendezvous point for the Persian army and fleet. As noted by Barry Strauss, professor of History and Classics at Cornell University:

“Nimbleness was not the trademark of the Achaemenid way of war … Big and slow was how they liked their military, both to overwhelm the enemy and to impress their own subjects. A massive expeditionary force needed a big base of operations.”

Why were the Persians so adamant about conquering Egypt? One reason is because the various empires in the Levant and Middle East considered Egypt to be a major threat. That is just one more reason for their desire to control Palestine – a fertile land with a long coast, and a convenient origin for attacks on Egypt. Or, at least, to contain Egypt’s influence over the Levant.

So not only were the Mediterranean plains fertile, with plenty of space and grasses for horses: it was close to Egypt and was relatively safe ground for Cambyses to slowly prepare for his invasion, Lehmann sums up.

The forces Cambyses massed on the coast would have needed a huge apparatus and an incredible amount of resources. Tel Keisan would have been only one of a series of supply points along the Acre plain, Indeed the archaeologists found remnants of storage jars and cooking pots in large quantities that may have been used Cambyses’ armies. A key bit of evidence was a large pit with organic debris and substantial quantities of pottery, some of which was Phoenician pottery some imports from Greece, mainly from Athens.

After the Achaemenids

Sadly, the architecture of the Persian period at Tel Keisan was severely damaged when the armies of the Hellenistic ruler, Alexander, ravaged the land as they drove out the Persians (under King Darius) in the second half of the 4th century BCE.

After Alexander’s death in 323 BCE, his kingdom was divided up among his generals. This fine company of generals is usually referred to as the diadochi, simply meaning successors, in plain English. War among the diadochi broke out almost immediately. As the great German historian Niebuhr once put it:

“It is simply a matter if one or the other bandit will get the upper hand.”

Over the next century, Ptolemaic Egypt and Seleucid Syria would be interlocked in a sweaty struggle over Palestine. It is highly probable that Alexander and subsequent Hellenistic rulers of what would become the Holy Land simply took over the infrastructure of the Persian Empire in the Acre plain. As noted by Strauss:

“Alexander and his successors were generally more interested in war than administration … It was cheaper and easier to take over the infrastructure of the Persian Empire. They demonstrably did so elsewhere and surely did in the Akko Plain as well.”

The Hellenistic levels represent what appears to be an industrial area with refuse pits and installations that yielded large quantities of pottery. The ceramic finds indicate that the link with the Mediterranean remained strong, and that trade with the Greek islands and the coast of Asia expanded until the 3rd century B.C.E.

Bust of Seleucus Nicator (“Victor”; c. 358 – 281 BCE), the last of the original Diadochi (National Archaeological Museum & Haaretz).

During the earlier Hellenistic period, Keisan remained a surburb to Acre – whose name had been changed to Ptolemais.

Some time during the later Hellenistic period, the settlement was abandoned. It would remain bereft of life during the Roman era, and afterwards, would be fitfully occupied and deserted. During the Byzantine period, the settlement was reinstated and a church with service buildings were built there. The foundations of the church are well preserved and were excavated and published by the French expedition.

But apparently by the early 8th century C.E. the mound was abandoned again, then resettled during the medieval period. From the 12th to the 16th century CE, the hill sustained a small rural site – which, in the early Ottoman period, would be abandoned, once and for all.