The article “A birthplace of musical instruments” was posted in the Tehran Times on January 8, 2022.

Kindly note excepting one image, all other accompanying images, videos and accompanying captions do not appear in the original Tehran Times article. The article below has also ben slightly edited in comparison to its original version in the Tehran Times.

===================================================================================

As per mythological traditions, the initiation of music in Iran is stated to date back to the time of the mythical king, Jamshid. However, fragmentary documents from various periods, including rock-carved carvings, suggest millennia of musical practices in every corner of the ancient land.

Tomos Brangwyn, a British hammered dulcimer player performs the Chaharmezrab Nava (سنتور – چهارمضراب نوا) on the Persian Santur; this musical piece was originally arranged by the late Iranian composer Faramarz Payvar (1933-2009) (Source: YouTube: WYNMOS). For more on the Persian Santur, consult Pars Times …

Archaeological records of Elam, the oldest civilization in the southwestern Iranian plateau, suggest the ancient land is the birthplace of the earliest complex instruments, which date back to the third millennium BC.

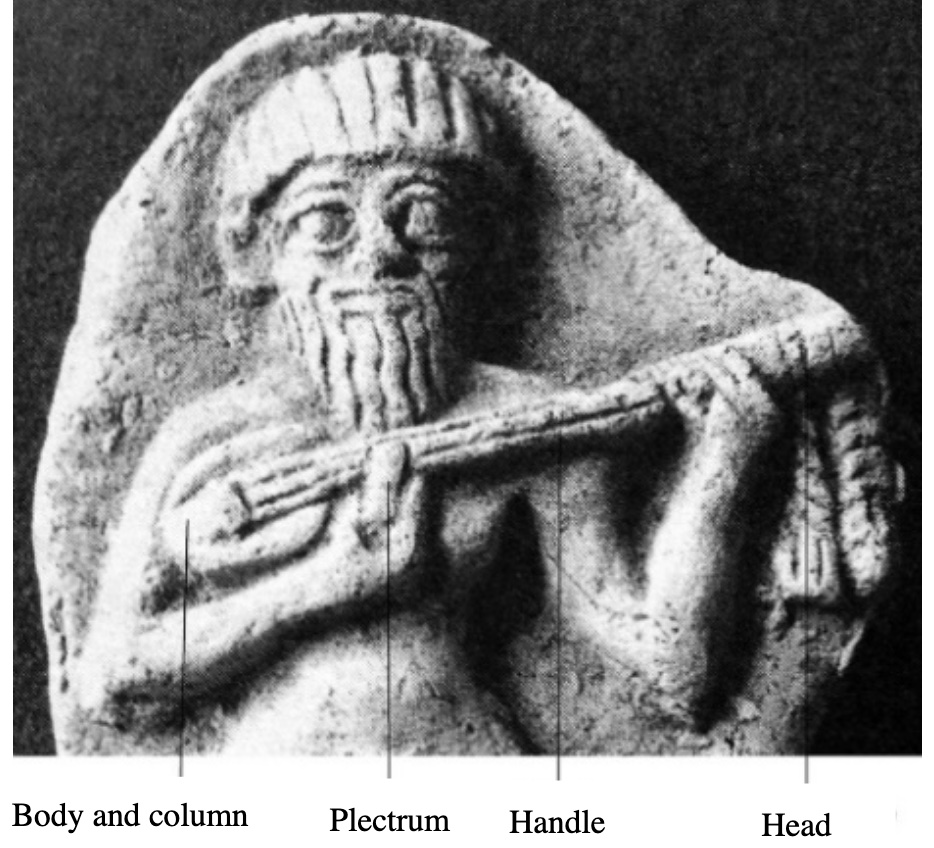

Elamite Lute player from Susa (image constructed of baked clay) currently housed at the Louvre Museum (Source: Figure 9, p.38; Rostami, M., & Mansourabadi, M. (2020). String Instruments Depicted in the Paintings of Ancient Elam. The International Journal of Humanities, Volume 27, Issue 2, pp.29-42).

Archeologists have discovered many trumpets made of silver, gold, and copper were found in eastern Iran attributed to the Oxus civilization and date back between 2200 and 1750 BC. The use of both vertical and horizontal angular harps has been documented at the archaeological sites of Madaktu (650 BC) and Kul-e Fara (900–600 BC), with the largest collection of Elamite instruments documented at Kul-e Fara. Multiple depictions of horizontal harps were also sculpted in Assyrian palaces, dating back between 865 and 650 BC.

Lute player statue from the time of the Parthian Empire (247 BCE – 224 CE), currently housed at the Netherlands’s Rijksmuseum van Oudheden (Source: Tehran Times).

The Sassanian period (226-651 CE), in particular, has left us ample evidence pointing to the existence of a lively musical life. The names of some important musicians such as Barbod, Nakissa, and Ramtin, and titles of some of their works have survived.

Iranian woman from approximately 260 CE, during the early Sassanian era, playing the harp as depicted in a Roman-style marble mosaic from the place of Shapur I at Bishapur (currently housed at the Louvre Museum) (Source: Public Domain).

With the advent of Islam in the 7th century CE, Persian music, as well as other Persian cultural taints, became the main formative element in what has, ever since, been known as “Islamic civilization”.

According to Encyclopedia Iranica, Persian musicians and musicologists overwhelmingly dominated the musical life of the Muslim lands. Farabi (d. 950), Ebne Sina (d. 1037), Razi (d. 1209), Ormavi (d. 1294), Shirazi (d. 1310), and Maraqi (d. 1432) are but a few among the array of outstanding Persian musical scholars in the early Islamic period.

Hailing the onset of the Iranian New year or Nowruz in the city of Dushanbe in Tajikestan. Nowruz is not just celebrated by Iranian speakers such as the Tajiks but by many Turkic peoples, including the Uzbeks of Central Asia. Iranian and Turkic peoples in Central Asia, the Caucasus, and Western Asia continue to share powerful historical bonds in architecture, music, the arts, cultural values and traditions.

In the 16th century, a new “golden age” of Persian civilization dawned under the rule of the Safavid dynasty (1499-1746). However, from that time until the third decade of the 20th-century Persian music became gradually relegated to a mere decorative and interpretive art, where neither creative growth nor scholarly research found much room to flourish.

Since the early 20th century, once again, Persian music began to find broader dimensions. An urge to create rather than merely perpetuate the known tradition, and an interest to investigate the structural elements, has emerged.

Today, in a progressively modernizing society, they are generally engaged by broadcasting and television media. They are also active as teachers both privately and at the various scholars and conservatories of music.

The 6th century BCE Achaemenid Karna is made of bronze, an alloy of copper and tin (Source: Iran Front Page). It was unearthed back in 1957 in the Persepolis compound, according to a Persian report by Carnaval website. Currently housed at the Persepolis Museum in southwest Iran, he length of this ancient wind instrument is 120 centimeters. The diameters of its outside and inside bell are respectively 48cm and 5cm. For more on this instrument see “A 2600-Year-Old Instrument on Display in Persepolis Museum“.

When it comes to structure, perpetuated through an oral tradition, the classical repertoire encompasses a body of ancient pieces collectively known as the “radif” of Persian music. These pieces are organized into twelve groupings, seven of which are known as basic modal structures and are called the seven “dastgah” (systems).

They include : Shur, Homayun, Segah, Chahargah, Mahur, Rast-Panjgah, and Nava. The remaining five are commonly accepted as secondary or derivative dastgahs. Four of them: Abuata, Dashti, Bayat-e Tork, and Afshari are considered to be derivatives of Shur; and, Bayat-e Isfahan is regarded to be a sub-dastgah of Homayun. The individual pieces in each of the twelve groupings are generally called “gushe”, but each gushe has a specific and often descriptive title. A gushe is not a clearly defined musical composition; rather, it represents modal, melodic, and occasionally rhythmic skeletal formulae upon which the performer is expected to improvise. Thus, the radif submits an infinite source of musical expression. The flexibility of the basic material and the extent of the improvisatory freedom is such that a piece played twice by the same performer, at the same sitting, will be different in melodic composition, form, duration, and emotional impact.

A musical piece by the Yulduz Turdieva Musical ensemble from Uzbekistan (Source: Morgenland Festival Osnabrueck). Yulduz Turdieva sings in Persian accompanied by Uzbek musicians composing Classical Persian music.

For those with a passion for music, it is worthy to spend a few hours in one of the museums dedicated to the music of the nation. An example is the Isfahan Music Museum located in the Armenian quarter of Jolfa in Isfahan. It showcases 300 regional and national musical instruments.