The posting below highlights Professor B. A. Litvinsky’s discussion of Achaemenid and post-Achaemenid helmets in an article on pre-Islamic helmets in the Encyclopedia Iranica on December 15, 2003.

====================================================================

Helmets came into use in the Middle East at a very early date. Among the oldest recovered specimens are Sumerian bronze helmets of the mid–3rd millennium B.C.E. from the royal cemetery of Ur. During the 9th–7th centuries B.C.E., bronze and iron helmets of different types became widespread in the Assyrian Empire. In the Caucasus region, local craftsmen influenced by Assyrian industry produced several types of Urartian helmets, mainly in bronze but some also in iron. The Iranian tradition of helmet making is very old. Elam produced hemispherical bronze helmets with decorative figures of deities and also one of a bird—perhaps a type of raptor. (See Figs 1–54 for this and the following examples.) The figures were first sculpted in bitumen, then overlaid with thin layers of silver and gold; and further details were incised, such as figures of gods. Some of them are masterpieces unequaled in ancient Near Eastern art. They can be dated to the 14th century B.C.E. (Muscarella, 1988, pp. 223-29). A number of bronze and iron helmets dating from the 9th-8th centuries have been found at western Iranian sites (e.g., Ḥasanlu, Mārlik, Safidrud). They are either conical or hemispherical, and some of them are richly decorated.

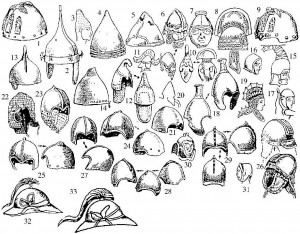

Figures 1-33. Pre-Islamic helmets, 14th–2nd centuries B.C.E. 1. Elam, 14th cent. B.C.E. 2. Luristan. 3. Marlik. 4-8. Ḥasanlu. 9. Safidrud. 10. Ḵᵛorvin. 11-12. Luristan. (Nos. 2-12 dated to the first third of the first millennum B.C.E.) 13. Achaemenid helmet, from Egypt. 14. Achaemenid helmet, from Olympia. 15. Oxus Treasure (British Museum). 16-17. Helmets represented on seals. 18. Achaemenid helmet, from Azerbaijan. 19. Achaemenid helmet depicted on a 5th-cent. B.C.E. Greek vase. 20. Achaemenid helmet represented on a rock relief, Lycia. 21. Achaemenid helmet (Glasgow Museum). 22. Scythian helmet, from the Kuban, 7th-6th cent. B.C.E. 23-24. Scythian helmets, Checheno-Ingushetia, 7th-6th cent. B.C.E. 25. Scythian helmet, 7th-6th cent. B.C.E. 26. Scythian helmet (Greek helmet of the Thracian type, refashioned by Scythians), Nymphai, 7th-6th cent. B.C.E. 27. Saka helmet from the Altai region, 7th-6th cent. B.C.E. 28. Saka helmet from the Talas valley, 7th-6th cent. B.C.E. 29. Saka helmet in the museum of Samarkand. 30-31. Saka helmet, from the Talas valley, 7th-6th cent. B.C.E. 32-35 and 37-38. Helmets represented on coins of the Greco-Bactrian kings (32. Eucratides I; 33. Amyntas).

Ancient Iranian languages provide a number of terms relating to helmets. The list of a fully-equipped warrior’s armament in the Avesta (Vd. 14.9) includes sāravāra- (“head-cover,” AirWb., col. 1572; see also EIr. II, p. 490); but the usual Avestan term for helmet is xaoδa- (AirWb., col. 531), which parallels Old Pers. xaudā-. Cf. Osset. xud, xodœ; New Pers. ḵöï, ḵöd, ḵōd (Kent, Old Persian, p. 180), Pers.-Tājik xoï, xod (Abaev, 1989, pp. 243-44). The Avesta mentions metal helmets made of bronze, gold, and iron (Yt. 9.30, 13.45, 15.57). Sometimes the shape is also indicated. Thus urwi-xaoδa- (Yt. 9.30) designates a helmet with a pointed top (Brandenstein and Mayerhofer, 1964, pp. 45-46; Malandra, 1973, p. 284). Middle Persian has several terms for helmet: sārwār (sārwār i batimen “bright helmet”), xōd, xoy, and targ or tarak (AirWb., col. 1572; Taffazzoli, 1993/94, pp. 191-93).

Classical authors provide some information on Persian helmets of the Achaemenid period. According to Herodotus (7.84), the cavalry of Xerxes included some Persians who “wore helmets of bronze and wrought steel.” Xenophon reports that mounted warriors, charioteers, and soldiers forming the king’s bodyguard wore helmets; and he adds that the helmets worn by rulers were of gold, i.e., gilded (Cyropaedia 6.1.51, 6.4.1-2, 7.1.2; Anabasis 1.8.6). Helmets are also mentioned in Babylonian documents of the Achaemenid period (Ebeling, 1952, p. 208). In later Greek and Roman sources, when the inhabitants of Central Asia are described, helmets—kranos or galea (helmet of leather)—are mentioned, but only in connection with Arians (Diodorus 17.83; Curtius 8.4.33; see Litvinsky and P’yankov, 1966, p. 43). Of the few actual finds, the most interesting is a bell-shaped helmet of gilded bronze from Olympia, which bears a Greek inscription stating that it had been captured from the “Medes” at the beginning of the 5th century, possibly in the battle of Marathon (Mallwitz and Herrmann, 1980, p. 96, Pl. 58). Helmets are also represented on a number of art objects. A fine example is that worn by a warrior depicted on a gold plaque from the Oxus Treasure (Dalton, 1964, pp. 73-74, Pl. XV, no. 84). In the 6th century B.C.E., bronze helmets of the Kuban type (named after finds in the basin of the Kuban River) were in use among the Scythians of Central Asia and the northern Black Sea. These were cast, and egg-shaped, deeper towards the back and with a wide opening in front. They were provided with longitudinal crests and holes along the edge to fasten the helmet to a mail piece. Their origin is disputed; some argue for the Middle East, others for China. In the 5th to 3rd centuries B.C.E., modified Greek helmets of the Corinthian, Chalcidian, Attic, and Thracian types were in use (Chernenko, 1968, pp. 74-98, figs. 39-59). During the Hellenistic period, certain types of Hellenistic helmets, especially the Boeotian type and its local variants, became popular in Iran, Afghanistan, and Central Asia. The clearest evidence is provided by the portraits of Greco-Bactrian rulers on their coins and by bronze and iron moveable cheekpieces discovered in the Oxus temple in Bactria.

Bibliography:

V. I. Abaev, Istoriko-etimologicheskiĭ slovar’ osetinskogo yazyka (Historical-etymological dictionary of Ossetic), IV, St. Petersburg, 1989.

A. M. Belenitskiĭ, Monumental’noe iskusstvo Pendzhikenta: Zhivopis’. Skul’ptura (Monumental art of Penjikent: painting. sculpture), Moscow, 1973.

St. Bittner, Tracht und Bewaffung das persischen Heeres zur Zeit Achaemeniden, 2nd ed., Munich, 1985.

A. D. H. Bivar, “Cavalry Equipment and Tactics on the Euphrates Frontier,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 26, 1972, pp. 273-307.

W. Brandenstein and M. Mayrhofer, Handbuch des Altpersischen, Wiesbaden, 1964.

O. M. Dalton, The Treasure of the Oxus, 3rd ed., London, 1964.

R. E. V. Chernenko, Skifskiĭ dospekh (Scythian armor),Kiev, 1968.

R. Du Mesnil du Buisson, “The Persian Mines,” in The Excavation at Dura-Europos. Preliminary Report. Sixth. Season of Work, New Haven, 1936.

Sh. Fukai and K. Horiuchi, Taq-i Bustan II. Plates, Tokyo, 1972.

E. Ebeling. “Die Rüstung eines babylonischen Panzerreiters nach einem Vertrage aus der Zeit Darius I,” Zeitschrift für Assyrologie und vorderasiatischen Archäologie, N.F. Bd. 16 (56), 1952, pp. 203-13.

Sh. Fukai et al., Taq-i Bustan IV, Tokyo, 1984. R. Ghirshman, Iran. Parthians and Sassanians, London, 1962.

M. V. Gorelik, “Zashchitnoe vooruzhenie persov i mid-yan achemenidskogo vremeni” (Persian and Median armor in the Achaemenid period), VDI,1982, 3, pp. 90-106.

Idem, “Kushanskiĭ dospekh” (Kushan armor), in G. M. Bongard-Levin ed., Drevnyaya India. Istoriko-kul’turnye svyazi, Moscow, 1982.

S. V. Grancsay, “A Sasanian Chieftain’s Helmet,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, April 1963, pp. 253-62.

P. O. Harper, The Royal Hunter. Art of the Sasanian Empire, New York, 1978.

G. Hermnann, Naqsh-i Rustam 5 and 8. Sasanian Reliefs Attributed to Hormizd II and Narseh (Iranische Denkmäler. Lieferung 8. Reihe II: Iranische Felsreliefs D), Berlin, 1977.

A. Invernizzi, Sculpture di metallo da Nisa. Cultura greca e cultura iranica in Partia (Acta Iranica, ser. 3, vol. 21), Lovanii, 1999.

S. James, “Evidence from Dura Europos for the Origin of Late Roman Helmets,” Syria 63, 1986, pp. 107-34.

B. A. Litvinsky, “History of the Helmet in Bactriana,” Information Bulletin of the International Association of the Cultures of Central Asia No. 22, Moscow, 2000.

Idem, Khram Oksa v Baktrii (Yuzhnyĭ Tadzhikistan), Tom. 2. Baktriĭskoe vooruzhenie v drevnevostochnom i grecheskom kontekste (The temple of the Oxus in Bactria [South Tadzhikistan].

Bactrian arms and armor in the ancient Eastern context), Moscow, 2001, pp. 364-81 (with detailed bibliography).

B. Litvinsky and I. V. P’yankov, “Voennoe dele y narodov Sredneĭ Azii v VI- IV vv. do n. e. (Warfare of the peoples of Central Asia in the 6th–4th centuries B.C.E.),” VDI , 1966, 3, pp. 36-52.

W. Malandra, “A Glossary of Terms for Weapons and Armor in Old Iranian,” IIJ 15/4, 1973, pp. 264-89.

A. Mallwitz and H.-V. Herrmann, eds., Die Funde aus Olympia, Athens, 1980.

O. W. Muscarella, The Bronze and Iron. Ancient Near Eastern Artefacts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1988.

B. J. Overlaet, “Contribution to Sasanian Armament in Connection with a Decorated Helmet,” Iranica Antiqua 17, 1982, pp. 189-206.

V. A. Raspopova, Metallicheskie izdeliya ran-nesrednevekovogo Sogda (Metal artifacts in early medieval Sogdiana), St. Petersburg, 1980.

V. A. Shish-kin, Varakhsha, Moscow, 1963. M. Rostovtzeff, “Pictures Graffiti,” in The Excavations at Dura-Europos. Preliminary Report. Fourth Season of Work, New Haven, 1933.

A. Tafazzoli, “A List of Terms for Weapons and Armour in Western Middle Iranian,” Silk Road Art and Archeology, 3, 1993/94, pp. 187-98.

H. von Gall, Das Reiterkampfbild in der iranischen und iranisch-beeinflussten Kunst parthischer und sasanidischer Zeit (Teheranischer Forschungen, Bd. VI), Berlin, 1990.[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]