Kindly note that: (a) the text printed below has been edited from the original Hush-Kit article (b) excepting six images and one video, none of the other images and videos appear in the original Hush-Kit article and (c) none of the captions accompanying the images and videos below appear in the original Hush-Kit article.

Readers further interested in the topic of the Iranian air force during the Iran-Iraq War (1980-1988) and modern Iranian military history in general, are encouraged to consult the following resources:

- Iranian Military History and Armies 1900-Present

- Books on the History of the Iranian Force

- A Short History of the F-4 Fighter-Bomber in the Iranian Air Force

- A Brief Overview of the F-14A Tomcat in Iranian Service

- The role of the Iranian Air Force in Halting the Iraqi invasion in 1980

- The case of the Iranian F-14A Tomcat that downed three aircraft with a single Phoenix missile

- Western, Pakistani and Egyptian pilots flying Iraqi Combat Aircraft during Iran-Iraq War

- Farrokh, K., & Sánchez-Gracia, J. (2022). La Guerra Iran-Iraq [The Iran-Iraq War]. Historia de la Guerra, 29, pp.63-77.

For a comprehensive textbook on the military history of Iran from the Safavid era to the end of the Iran-Iraq war, consult:

See reviews of above text:

- Aboul-Enein, Y. (2012). Book Review of Iran at War 1500-1988. Small wars Journal, July 12

- Iran at war 1500-1988 (ایران در جنگ: ۱۹۸۸-۱۵۰۰). Reviewed by the Iran-based Library, Museum and Center of Manuscripts (May 20, 2012) (ارایه کتاب «ایران در جنگ: ۱۹۸۸-۱۵۰۰» در کتابخانه مجلس-(۳۱ اردیبهشت ۱۳۹۱

- Terpstra, R. (Sept 11, 2011). Iran at War, Business Daily Report of Egypt

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

The F-14 was the king of the air in the extreme combat of the Iran-Iraq War. Around 180 Iraqi aircraft fell to Grumman’s deadly Tomcat, of these kills, sixteen can be attributed to Col. Mazandarani. We spoke to the world’s greatest living ace to learn more.

Which three words best describes the F-14?

“Deadly, unpredictable by the enemy, hell of a ride!”

Fereydoun A. Mazandarani as 1st lieutenant of the Iranian force, seen in front of an F-14A Tomcat at the 8th air base at Isfahan in the summer of 1978 (Image Source: Hush-Kit).

What was the best thing about the F-14?

“I would have to say its powerful radar and variable sweep wings, but let’s not forget the manoeuvrability and great visibility.”

Mazandarani (1st person standing from the right) during his training with the T-38 (white jet with open canopy in background in background) in the early 1970s as a flight cadet in the US at Laughlin Air Force base (Image Source: Hush-Kit). The other pilots are a mix of American instructors and their student pilots. Mazandarani’s later training with the Tomcat was to take place in Iran at the Khatami Air Force base.

What was the worst thing about the F-14?

“I guess I would have to stick with the TF30-414 engine cliché, but if you knew how to handle it, it wasn’t that bad. The fact is, in almost 40 plus years of service and about tens of thousands of flight hours in the Iranian air force, the losses due to engine problems were fewer than a handful of Tomcats.”

How do you rate the F-14 in Instantaneous turn?

“I would give it a 100 because of its variable sweep wings.”

How do you rate the F-14 in Sustained turn?

“Another 100 Again because of its variable sweep wings and great aerodynamics.”

An F-14 Tomcat badge prior to 1979 (Image Source: Hush-Kit).

How do you rate the F-14 in High alpha?

“It is a 95 for this one. But it offered great control when flying with high AOA.”

How do you rate the F-14 in Acceleration?

“This was 95 out of 100, mostly due to the minimal lag of turbo fan engines compared to turbo jets or newer turbofan engines.”

How do you rate the F-14 in Climb rate?

“A+. It will receive a 100 when in zone 5 afterburner.

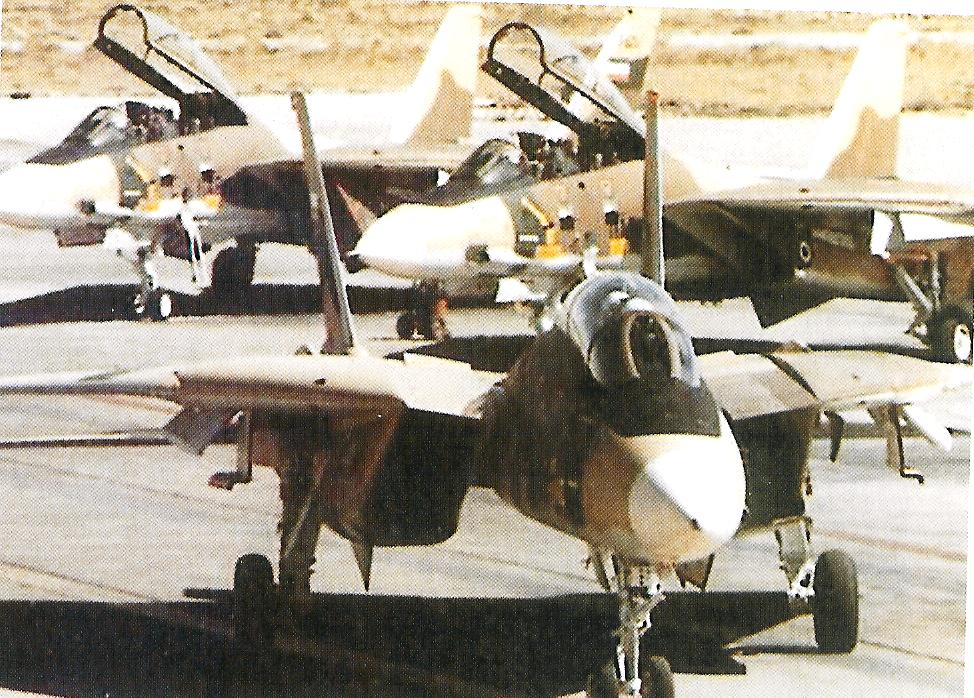

Freshly delivered F-14 Tomcats at the Iranian airbase of Khatami before the revolution (Cooper & Bishop, 2004, Color plate 3). For more see here …

How do you rate the F-14 in Sensors?

“The sensors especially the electronic countermeasures and electronic counter countermeasures at the time of delivery were top of the line. These performed quite well against AAMs and SAMs during the Iran-Iraq war. Unfortunately, the post revolution Iranian air force did not receive the IRST, and Data Link systems due to the hostage crisis and the ensuing arm embargoes. We could have made great use of them.”

How do you rate the F-14 in Man machine interface/cockpit?

“The cockpit layout and easy access to switches and gauges were fantastic compared to the F-5 aircraft I had flown. Moreover the F-14 offered unprecedented and greatly improved cockpit visibility.”

How do you rate the F-14 in Situational awareness?

“As mentioned above, the exceptional layout of the instruments and switches were quite useful in knowing the craft’s position. This along with the pilot’s awareness of his surroundings and position as well as foreseeing possible scenarios during engagements is of utmost importance. Of course, physiological conditions such as fatigue drastically reduces situational awareness as we witnessed during the war. In one instance, during a CAP mission on a moonless night around 0330 local time, I was returning to 8th tactical fighter base near Isfahan when I noticed another F-14 less than 200 metres away flying inverted with its gears extended upwards. I wasn’t sure about what was transpiring before my eyes since it was our standard operating procedure to turn off all aircraft navigational lights in combat conditions. I contacted the tower and they confirmed that my colleague J.Z. was on final approach. I gently radioed him and said, “Hey, I think you are vertigoed! Just roll right and level off.” Thankfully, he listened and levelled off moments before landing. But this story will always be with me as a good example of what fatigue and combat can do to a pilot.”

Iranian Tomcat Badge with Tomcat written in Persian [تامکت] (Image Source: Hush-Kit).

Tell me something we don’t know about the F-14.

“It might be news to your readers that the Iranian Air Force used the F-14A as ‘Bombcats’ on several missions during the war against Iraqi forces in mid 1980s, way before the US Navy did. The wing box of the F-14 is a masterpiece and so we never had any asymmetrical issues with the wings during all these years.”

How good was the Phoenix and what was your experience with the weapon systems?

“It was flawless. As far as I can recall, out of some 167 launched AIM-54A missiles, only in one instance did the missile malfunction. Our investigation and pilot record showed that the missile’s own engine didn’t ignite on time, and when it did, the missile actually followed the Tomcat. This missile was a successful weapon. And quite frankly since the AIM-54A Phoenix was the only standard missile received by the Iranian air force for use on the F-14, it was standard operating procedure to launch it from 20-25 miles out to ensure higher hit rate and also to keep our own F-14 jets safe from enemy air-to-air weapons.

Iran’s Sattar-1 laser-guided air-to-ground missile designed after the Iran-Iraq war. This is believed to have borrowed some features from the Phoenix air to air missile. The Phoenix downed large numbers of Iraqi air force aircraft during the Iran-Iraq war, including those flown by mercenary pilots (Picture source: Mashregh News).

As for my personal experience with it, I must say that I fired eight rounds of Phoenix missiles in total, from different positions and angles, which all hit their targets. My first experience firing the missile, was chasing a MiG-21 with enough speed to overtake it at 11 miles towards its aft hemisphere. This was September 1980.”

What was your toughest opponent and why?

“My own toughest engagement was with five Iraqi Mirage F1 fighter jets during my annual Stan/Eval check while on an S.M. (special mission) flight with Major J. Shokraee-Fard as instructor pilot. It took place near Nowruz Oil Field which had been attacked the day before by the Iraqi air force. I had actually briefed the pilots that same morning on how the Iraqis would probably attack: i.e. in two groups, one group flying at high altitude distracting the CAP fighter(s) while the other group snuck in low to strike the oil rigs.

As had been predicted, we encountered two groups heading our way from two directions. A flight of two, and a flight of three. As soon as we prepared to engage the enemy at 690 Knots and slightly over 50 feet above the water, I noticed that our Master Arm switch had failed leaving us defenceless. The hunter had become the hunted. The attacking Mirages fired six air-to-air Matra missiles or as we called them, Red Heads, at us. Making hard turns and pulling high Gs, we defeated the missiles and re-engaged them in a canopy to canopy dogfight. We were so close that in a couple of passes I could see the pilot’s white notepads strapped to their legs.

Iranian F-14s in combat during the Iran-Iraq war (Episode 1) (Source: Mike Guardia in Youtube).

Maj. Shokraee-Fard kept checking our six, advising me of enemy position while I kept manoeuvring hard keeping myself out of their gun or IR missiles lock. During one of these manoeuvres we saw one Mirage crash into the water while the others returned to base. Once we were clear, I noticed that my G-suit had ruptured from the pressure and my helmet had cracked hitting the canopy. On our way back to base, we were advised by ELINT and the local ground radar that only three of the five Mirages had returned. After the flight, Maj. Shokraee-Fard had to wear a neck brace for six months while I suffered injuries to my knees which resulted in two surgeries after my retirement. The G meter was locked at 11.5Gs on the gauge which required the Tomcat to go through Non-Destructive Inspection (NDI). The analysis showed 19 cracks and fractures along the longitudinal axis of the aircraft which put it out of service for almost two years. We were really lucky that day.”

What was life like in your unit during the war? What were the biggest highs and lows?

“In the early days and weeks, the high losses of our pilots in the F-4 and F-5 squadrons were especially hard and painful, affecting the overall morale. It was quite bleak. As the days went by, we realised that the only available force that could slow down the rapid advance of the Iraqi ground forces was the air force and so they came to terms with the fact and accepted it. After a few weeks, despite the repeated loss of our colleagues, the missions continued without any problems and the bitter realities of war became routine. We had no choice. Iran’s ground forces were in disarray after the revolution, as a result of widespread purges – and in many cases they were no match for the Iraqi onslaught. Therefore the air force took it upon itself to act as speed bump against Iraqi ground units until our own soldiers could be organized into an effective fighting force. We performed CAS (close air support), while providing BARCAP to our own cities and infrastructure.

Iranian F-14s in combat during the Iran-Iraq war (Episode 2) (Source: Mike Guardia in Youtube).

My biggest high was to be the first person in Iranian AF pilot to have done a night refuelling in an F-14. We were not trained to do this by our former US Navy instructors so I was quite proud of myself for doing something like that. The biggest low would be losing three F-14s within a short few days to the French built Mirage F1 used by Iraqi AF. That hurt our pride badly.”

Tell me about your kills please.

“I had eight aerial kills with the Phoenix missile, two kills with the Vulcan M61A gun, and one kill with the MIM-23 Hawk missile that we ended up using on our fleet of F-14 jets due to severe missile shortages in late stages of the conflict. On top of that I reportedly can claim five maneuver kills from two separate engagements.

My first air-to-air kill was a few days before the official start of the war Sept 17, 1980 when two Iraqi MiG-21s were on a bombing run over the city of Mehran in western Iran. The ground radar guided us toward the Iraqi fighters and we approached them in a way that I ended up 13 to 15 miles behind one of them at 3,000 feet. I was flying with my RIO Lt. Sultani, at over 240 knots faster than the Iraqi fighter when I fired my Phoenix missile and watched an aircraft disintegrate and explode visually for the first time.

My second & third kills were with RIO Lt. Najafi on Sept. 25, 1980 flying over the general area of Dezful in SW Iran. We were informed by ground control radar that four MiG-23s had crossed the border. We were directed towards them and at around 45NM locked our radar on the fighters. They reduced their altitude and turned towards Iraq flying in between the mountains. At one point my RIO noticed that he only had two radar signatures and when we checked with ground radar, they also confirmed two targets. My sixth sense told me that this was a ruse and that only two of the fighters had actually returned. I turned the plane around, and within mere seconds re-acquired the missing two hostile aircraft flying at 100ft heading for the city of Yasouj. We immediately locked on both targets and launched two Phoenix missiles. One of the MiG pilot survived the ejection and was later captured.

Iranian F-14s in combat during the Iran-Iraq war (Episode 2) (Source: Mike Guardia in Youtube).

My fourth kill was a MiG-23. My RIO on this mission was Lt. Ahmadi. We were providing top cover for CAS missions on Nov. 13, 1980. This MiG was in pursuit of two Iranian AF F-5E Tiger jets returning from a close air support mission. Our position didn’t give us enough time to engage him with the Phoenix missile so we prepared ourselves for a knife fight. We both began turning into one another trying to get each other in our respective gunsight. We began spiralling downward in a rolling scissor manoeuvre. I opened fire with the gun twice, but didn’t think he was hit. I told my RIO to keep reading the altitude as we hurtled towards the earth. I kept hearing him read the altimeter: “2500ft, 2000, 1800, 1500, 1000, 600, 300” and then I pulled the nose up hard pushing the throttles to zone 5 afterburner, avoiding the ground. The moment I levelled off, I inverted the plane in time to notice a fireball on my left side. The MiG impacted the terrain. Honestly, I really would have wanted to meet with this skillful pilot and I felt bad about his sudden demise

My fifth & sixth kills were on Nov. 29, 1980, a day after the Morvarid (Pearl) naval operations that decimated the bulk of Iraqi naval forces in the northern Persian Gulf. My RIO on this day was Lt. Ibrahim Ansareen. The main objective of the operation was to destroy Iraq’s Al-Bakr & Al-Amaya oil terminals (now ABOT) in order to cutoff Iraq’s oil export. The enemy naval surface forces had lost several fast attack boats on top of a few Russian built corvettes to our well equipped navy. And so the Iraqi air force was tasked to provide cover for their helicopters trying to retrieve Iraqi troops and sailors lostat sea, or still on the oil platforms. Our job was to deny their top cover and also target their helicopters as they came in to reinforce their positions.

I took out one Iraqi MiG fighter aircraft with a Phoenix missile and continued playing cat and mouse with the remaining fighters. At another opportune moment, I launched a second AIM-54A Phoenix missile at another approaching MiG about 10 or 11 miles out resulting in a shoot down. Since my aircraft was loaded with only two rounds of AIM-54 Phoenix missiles, and therefore we were practically Winchester, I immediately called for support. Two of my buddies late Capt. H Farrokhi who was patrolling in another area as well as Capt. Jamshid Afshar came to replace us. These two men on that very day shot down 3 other intruding Iraqi fighter jets resulting in total shoot down of 5 enemy aircraft by our F-14 fighters in one single day.

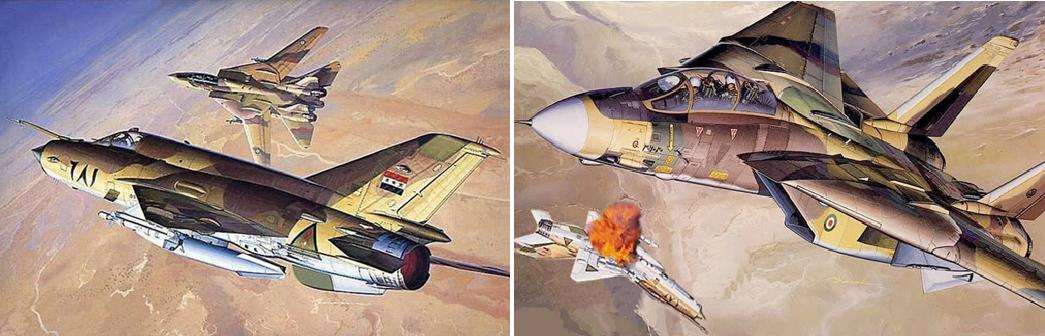

A two-phase painting of a dogfight between an Iranian Tomcat and an Iraqi MIG-21. At left the two adversaries are locked in combat and maneuvers and at right the Tomcat kills the MIG-21 (Picture source: Uskowi on Iran). It was on November 20, 1982, when a Tomcat like the one above fired its deadly Phoenix missiles into Iraqi MIG-21 and MIG-23 aircraft escorting a VIP Mi-8 helicopter ferrying Iraqi generals Abdul Jabbar Mohsen (Iraqi Fourth Army Corps) and General Maher Abdul Rasheed (Iraqi Third Army Corps). Three Iraqi combat aircraft were immediately blown to pieces. Luckily for the generals, their helicopter had not been detected by the Tomcat’s AWG-9 radar – otherwise they most certainly would have been blotted out of the sky by one of the Tomcat’s Phoenix missiles. General’s Mohsen and Rasheed had indeed had a “near-death experience”. For more see here …

My seventh kill happened on April 24, 1981, when 1Lt. Farrokh-Nazar and I were providing cover for our ground troops in the vicinity of Ahvaz. We were vectored by ground radar to intercept an aircraft heading for our friendly positions. We tracked him on our radar, and at about 20NM fired a Phoenix missile resulting in a shoot down.

My eighth & ninth kills happened on/about November 20, 1982 with Lt. Tahmasebi as my backseater. We received a NoTAM alert about the arrival of Saddam Hussein and/or a few high ranking officers to inspect the Iraqi battle areas. On that fateful day we could see that higher than normal Iraqi air activities which supported our initial intelligence about the presence of high ranking figures in the battle area. As usual, we’d lock onto the Iraqi fighters a few times and they would immediately turn around; however, during one of these radar locks the Iraqi fighter and its wingman continued its course towards us. Knowing who they were and what they were going to do, we fired two Phoenix missiles at them but could not really tell if those launches were successful. The moment we landed, we were summoned bv our angry wing commander. We were both given a written reprimand for not following the rules of engagement ROE as we had been directed. Apparently our ROE had directed us to engage the Iraqi fighters only inside the Iranian territory. We were also forbidden from crossing into Iraqi air space by our headquarters. This was set up to prevent the loss of prized F-14 aircraft with its sophisticated weapon system inside the enemy territory in case of a mishap or loss to enemy fire. The air force brass had also feared our top secret AIM-54A missiles would somehow end up in enemy hands if it was fired at enemy fighters inside the enemy air space. As a result, we were not credited for these two kills. However, 31 years later in 2013 ‘IRIAF’s Center for Study & Research’ officially registered these 2 kills in our names.

My tenth kill was in Northeast of Boubian Island with Lt. S. Shokouh in Feb 1984. The target was a Mirage F1 that we destroyed using the nose gun. We were patrolling in sector 3, close to Minoo Island south of the city of Abadan when we encountered a single Mirage flying low. We didn’t have enough time to prepare a radar lock. I managed to get myself to his 4 o’clock. Switching to PLM for close combat or dogfight, I locked onto the Mirage but the pilot immediately went into full afterburner and began jinking preventing us to get on his six.

I managed to maneuver myself to about 25 degrees off of his tail using afterburner as we flew below 100ft AGL. At a distance of 500-700ft I opened up at him. Took two bursts of the F-14’s Vulcan M61A1 canon to effectively strike the Iraqi fighter. The Mirage caught fire and unfortunately, the pilot didn’t have enough time to eject at that high speed and in a very low altitude. The burning fighter slammed into the ground and explode

An Iraqi air force Su-22 (left – Picture source: Flying Tigers: The Aeroplane People) and a Su-22M shot down near Baneh in northwest Iran on October 16, 1987 (right – picture source: Farzad Bishop). The doomed Sukhoi was first targeted for termination by an Iranian Tomcat forcing the Iraqi jet to dive extremely low – the Su-22 did this to avoid being blasted by the Tomcat’s Phoenix missile. This only led the doomed jet into the sights of Iranian 35mm anti-aircraft guns which shot down the aircraft.

My eleventh kill took place in September 16th, 1986 during the live firing test of the US made MIM-23 Hawk surface to air missile carried by the Iranian F-14. Quick background should be provided here. The late Shah’s air force had ordered plenty of AIM-7F Sparrow and AIM-9L sidewinder air to air missiles along with the AIM-54A missiles for our new fleet of the F-14s. But the hostage crisis of 1980 effectively killed the prospect of the arrival of the former missile types thus the Iranian F-14s and crew went to war only with AIM-54A being F-14’s standard missile. The two versions then available in our inventory, namely AIM-7E and AIM-9J, were not really compatible with the F-14’s fire control system. The MIM-23B Hawk SAM was the only medium range anti-aircraft missile in our inventory. We adapted it for our F-14 and it was called AIM-23C Sedjil. I was a senior member of the team that worked on converting the Hawk surface to air missile to an air-to-air missile. During the final trial run, I was ordered to test the missile during an actual combat situation to prove the system to naysayers. I was sent TDY to Bushehr 6th tactical air base to stand scramble alert. I think it was on the third day when the opportunity arrived to demonstrate the combat capability of this new weapon. My backseat was 1Lt. Ansareen.”

The F-14 at left is piloted by Fereydoun Mazandarani at the time the above photo was taken (Image Source: Hush-Kit). Interestingly, Mazandarani’s aircraft is armed with the MIM-23 Hawk missile (note the red fins), an anti-aircraft missile which the Iranians successfully modified for air-to-air combat. Mazandarani was a member of the same technical team which worked on converting the MIM-23 from its original role as a surface to air missile into an air-to-air weapon.

“We locked on and fired the first Hawk which turned out to be dud. The missile made a barrel roll over the nose cone of the F-14 and fell straight down. I immediately fired a second one at 20NM resulting in positive hit as confirmed by our SIGINT and radar data. I am told the target was a French built Dassault Super Etendard maritime strike aircraft leased to the Iraqis in mid 1980s. This specific Super Etendard’s tail number must have been 4667 piloted by Captain A. Kamal Hussein.

Western Europe, especially France worked hard to train as many high-quality Iraqi airmen and ground crew as possible – above is a rare photo of Iraqi air force personnel posing in front of a French Navy Super Etendard sometime in the early 1980s; Fereydoun Mazandarani shot down an Iraqi air force Super Etendard with an Iranian-modified Hawk missile from his F-14 platform in 1986. Note European-looking male in above photo (back row, standing, 2nd from left), possibly a French military trainer and/or liaison to the Iraqis (there are other possible French personnel mixed in the above photo) (Source: مقالات نظامی). The Western effort to produce an all-Iraqi pilot force for Saddam’s air force proved impossible to achieve due to high losses to Iranian combat aircraft and ground-based missiles – for more on this topic see “Western, Pakistani and Egyptian pilots flying Iraqi Combat Aircraft during the Iran-Iraq War” …

These maritime strike jets were used extensively by the Iraqi air force to strike our cargo ships and oil tankers using their infamous Exocet missile. And as you know they had a rather stellar record during the Falklands war against the Royal Navy surface assets as well.”

How did you feel going into combat in the F-14?

“Very confident. The truth is as the war dragged on the feeling of resignation took over our units. We felt the war would go on longer than we had hoped for. With the prospect of an immediate ceasefire fading, we decided to preserve our irreplaceable number of AIM-54A missiles by resorting to engaging enemy aircrafts in dogfights – meaning we would get close to them and use our superior techniques and tactics to shoot down enemy aircraft. I just want to tell you how confident all of us felt about the F-14 Tomcat that even when the Mirage F1s were added to the Iraqi air force fleet, that confidence was still there. Yes, they managed to create a headache for us, but we quickly overcame that threat and regained the upper hand.

Takeoff! An Iranian Tomcat taking off, armed with air-to-air missiles (Image Source: Hush-Kit). Iranian Tomcat would often be faced with multiple enemy aircraft which were increasingly flown by non-Iraqi mercenary pilots such as Max von Rosen and Gustav Miller from Belgium – for more on this topic see “Western, Pakistani and Egyptian pilots flying Iraqi Combat Aircraft during the Iran-Iraq War” …

To further prove my point, during the eight years of war, Iran only lost 5 Tomcats to enemy air activity. These losses initially were due to the lack of intelligence on the presence of Mirage F1s in the area, and more so being ambushed by several Iraqi F1 fighters for 4 of the Tomcat losses. They had to ambush and overwhelm the F-14 but one on one they really had no chance. Needless to say, and for variety of reasons our main objective as F-14 crew in the latter stages of the conflict was to make the Iraqi air crew abort their missions mid flight. We were quite successful in doing that. And this is how it worked: As soon as the Iraqis found out that an F-14 Tomcat was patrolling in the area they would abort and RTB. Or we would just lock on them, and the radar lock alone made them hightail it back to their own side.”

How Combat effective was the F-14, and how important was it in the war?

“It can’t be measured. In my opinion, the presence of the Tomcat in the Iranian air force was the highlight of aerial combat during the Iran Iraq war. Saddam’s strategic miscalculation of the strength of Iranian air force during the chaotic months after the 1979 revolution led him to believe the Iraqi army would march triumphantly in Tehran within a few weeks and never thought that the Iranian air force could utilise all of its capabilities including the use of the F-14 Tomcats. The chaos stemmed from the purges and executions that decimated the whole of former Imperial Iranian armed forces. Most of our leaders above the rank of colonels, were either, executed, imprisoned, discharged or had left the country. Among them were outstanding war planners and tacticians. Adding to this chaos, was the low morale in the armed forces as a result of the Islamic revolution. Despite the military and economic support from twenty plus countries including the regional Arab states, The Soviet Union, France, both West & East Germany, United States… etc, Iraq was never able to maintain air superiority during the 8 year war all because of the magnificent Grumman Tomcat.

Iranian pilots and crew proudly pose with their venerable Tomcat. Iranian Tomcats faced vastly superior numbers of Iraqi aircraft, many of these piloted by non-Iraqi mercenary pilots. Iranian airmen such as these proved their mettle in supporting Iranian ground and naval forces in defense of Iranian territory and the Persian Gulf. Few as yet are aware of the incredible achievements of Iranian combat aircraft (especially the F-14 Tomcat) against Soviet-designed Tu-22, MIG-21, MIG-23, MIG-25, Su-22, Su-25 and French-designed Mirage F1EQ combat aircraft (Picture source: Cooper & Bishop, 2004).

What is the biggest myth about the Iranian F-14s?

“The most tiresome is that the departing US personnel stationed in Iran managed to sabotage Iranian F-14 radar, electronics and Phoenix missiles before leaving Iran in the ensuing days after the 1979 revolution. Let me tell you that I was a young officer during those days at Esfahan Khatami air base. Our wing commanders and senior officers made sure this never happened. We lined up departing American personnel before boarding their TWA aircraft and inspected them all. Another myth that needs to be shot down right now is myriad of statements by F-14 enthusiasts boasting about shooting down Iraqi fighters from a distance of over 150km! That is untrue.

The F-14A remains in service with the Iranian air force, long after the end of the Iran-Iraq war in 1988. Above is a video of an Iranian F-14A scrambling for a nighttime mission (Source: Iran Army in Youtube).

What should I have asked you?

This is a good opportunity to clear the air. The following quick Q/As are rather important in my opinion:

What was the F-14’s kill ratio during the Iran Iraq war?

Between 155-160 kills with the Phoenix missile. Roughly 10 enemy aircraft fell victim to AIM/7E Sparrow, AIM/9J Sidewinder, MIM-23 (AIM-23C) & M61A nose gun.

Roughly 8-10 maneuver kills, or their running out of fuel in aerial combat and never reaching a friendly airfield.

Combat recreation of a single Iranian F-14 from Shiraz Airbase successfully intercepting three Iraqi Air Force Mirage F-1s (Source: Growling Sidewinder in Youtube). What remains unknown is how many mercenary French, Western, East Block and other non-Iraqi pilots were killed in air to air combat against Iranian Tomcats.

The number of Iranian F-14 losses that fell to enemy aircraft stands at five. This is a kill ratio of 1:35 to 1:37.

While Iranian F-14 Tomcats often outperformed Iraqi Air Force combat aircraft (flow by Iraqi and non-Iraqi mercenary pilots), up to five Tomcats (Source: Showtime 112 in Youtube). In practice the Tomcat remained the supreme air to air combat jet during during the 8 year (1980-1988)war, as the loss ratio was: one Tomcat lost in exchange for 35-37 Iraqi combat aircraft shot. Despite massive Western and eastern block assistance, Baathist Iraq continued to suffer massive losses in aircraft, despite the use of skilled Western, Pakistani, Soviet, etc. mercenary pilots – see the report “French pilots bombed Iran During Iran Iraq war” and note 4 minutes and 19 seconds into that program which reveals that “France not only supplied their best fighter planes to Saddam (president of Baathist Iraq) but also their pilots … the French began to fly air force missions for him (Saddam Hussein) … they [the French] were flying missions … Pentagon confirmed it … ” (Source: Cyrus Dariush in Youtube) “”.

Bear in mind that Iranian F-14s were fighting with one hand tied behind their back. Despite being on order, the AIM-7F Sparrow, And AIM/9L missiles were never delivered due to arms embargo, and we had a limited stock of very expensive Phoenix missiles.

What was your most memorable mission and why?

One of my most important and stressful engagements was on Thursday Mar. 21, 1985 along with RIO Lt. Sanatkar. I was on final approach returning to base from a 6hr combat air patrol. Wing command ordered us to cancel approach and fly back south as fast as we could due to lack of available covering fighters in that critical sector. I air refuelled and headed south towards Khark Island area to offer aerial protection for a convoy of some twenty massive oil tankers fully loaded with Iran’s one month worth of crude oil output. We were on station for more than an hour and nearing bingo fuel status with 8500 lbs left in the tanks. I was about to head to our tanker for another mid-air refuelling when the radar controller warned us of 10 approaching bogeys.

It did not take long when these bogeys became bandits. But the problem was that my aircraft was quite low on fuel for any engagement. We turned our F-14 heading south initially, but again turned to heading 300 degrees as 13 targets began appearing on the radar scope flying at 500ft ASL. We later found out they were eight upgraded MiG-23 bombers known as MiG-27* (or MIG-23BN?) and five French built Mirage F1s acting as escort. I had no choice but to engage the enemy fighters in order to protect the convoy of tankers from a horrendous air assault. I told my backseater to be ready to bail out whenever I instructed him to do so. I set my altimeter to 35ft ASL and thought out my engagement strategy as I began dropping altitude.

An Iraqi Mig-23 just before it was shot down by Iranian forces (left) and the remains of its unfortunate Iraqi pilot after the plane crashed (right) ( for more on this topic see “Western, Pakistani and Egyptian pilots flying Iraqi Combat Aircraft during the Iran-Iraq War” …). Iraqi Mig-23 aircraft suffered heavy losses at the hands of Iranian F-14s – despite much Soviet-East Bloc, French-Western, Pakistani and some Indian assistance, right up to the last days of the war.

At about 20NM, with our fuel at 2,000lbs the escort fighters fired some 20 Matra missiles at us aimlessly as the onboard ECM, Chaff and flares began to work their magic. We started defeating the missiles by making hard left and right turns called “Jinking” and turned into the Iraqi strike package. Fortunately, the MiGs jettisoned their payload and broke formation as we maneuvered between the enemy fighters and frightened them. The escort fighters which were flying in two groups had also broken formation and as I passed the last three Mirages, I banked hard and got behind them watching the Mirages light up their afterburners as they headed back. I thought of chasing them, but my fuel gauge was now reading 600lbs almost 50NM southwest of Khark Island, so I disengaged and eased back on the throttle to military power returning towards Bushehr air base.

Combat aircraft pilot: Interview with sixteen kill Grumman F-14 Tomcat ace – The F-14 was the king of the air in the extreme combat of the Iran-Iraq War. Around 180 Iraqi aircraft fell to Grumman’s deadly Tomcat, of these kills, sixteen can be attributed to Col. Mazandarani. The Hush Kit venue interviewed the world’s greatest living F-14 ace to learn more (Source: Hush Kit).

I asked Lt. Sanaatkar if we had been hit or anything but he confirmed that all systems were working just fine. I called the ground radar but didn’t receive a reply. I tried again and still got no reply. After my third call, the operator replied asking if we were still in our aircraft?! They had assumed we had been targeted by all those Matra missiles that had run their course and exploded mid-air. I told them that we may have to ditch the plane and may require immediate SAR helicopter over head. But right then I was interrupted by my dear friend Col. M. Reza Moharrami (nicknamed Mamish), the pilot of a KC-707 fuel tanker, saying that we will be shaking hands soon. To our astonishment this brave and marvel of a pilot had flown toward the engagement area faking radio communications with other aircraft to give the enemy side the false belief that more friendly fighter aircraft is headed to my engagement zone. We hooked up with the tanker at 2,000ft and gradually climbed to 22,000ft receiving much needed fuel in the process. On our way back to base, I was informed by ground based radar that one MiG-27* and two Mirage F1s had not been able to make it back which was icing on the cake!”

A tribute to one of the unsung heroes of the Iranian War Effort: the F-14A Tomcat seen in new air superiority colors maneuvers after the war. The role of the Tomcat in the defense of Iran cannot be underestimated. It would be no exaggeration to state that despite the small numbers of Tomcats available throughout the war, these more than compensated against the vastly superior numbers of Iraqi aircraft, especially in the latter stages of the war. (Picture Source: pp. 31 in “IRIAF: 75th Anniversary Review”, World Air Power Journal, Volume 39 Winter 1999 issue, pp.28-37).