The article “Parthian Warrior Grave Accidentally Unearthed During COVID-19 Burial” written by Ashley Cowie was published in Ancient Origins on May 4, 2020. This archaeology discovery was reported earlier in Radio Farda on May 1, 2020 and Tehran Times on April 29, 2020.

The reports in Ancient Origins and the Tehran Times however have failed to mention a seminal academic report (2018) of a series of excavations (in 2015) of scores of Parthian skeletons (male and female) buried alongside a (very) large number of weapons (swords, daggers, arrowheads, spear-tips, etc.) in Vestemin, Northern Iran. This report is available for download below in Academia.edu:

There are also a number of recent academic publications on the topic of Parthian militaria available for download in Academia.edu including:

Kindly note that excepting three images (one in Ancient Origins, Tehran Times and Radio Farda respectively) the version of the Ashley Cowie article printed below contains images and captions that do not appear in the original articles in the Tehran Times and Ancient Origins. The version below has also been edited from its original version.

===========================================================================

An ancient skeleton and burial artifacts of a Parthian warrior have been unearthed in Iran while excavators buried COVID-19 victims.

The skeleton and collection of ancient artifacts were discovered in a cemetery in the village of Paji (or Pachi) in Mazandaran Province, northern Iran, during the burial of a COVID-19 victim when an industrial digger brought them to the surface.

Mazandaran Province to the south of the Caspian Sea was one of the worst-hit Iranian provinces by the coronavirus pandemic and it is still categorized as a “red zone” by the Ministry of Health and Medical Education. Historian Mehdi Izadi, the Deputy Head of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage, Tourism and Handicraft Organization in Mazandaran Province, who is himself from the village of Paji, said the Iranian protocol for the burial of COVID-19 victims requires digging to a depth of 3 meters (9.8 feet) but in this instance:

“… the ancient remnants were discovered at a depth of 2.5 meters (8.2 feet).”

Left: archaeologists excavating the site. Right: part of the sword and skeletal remains of the Parthian warrior unearthed at the site (Source: Ancient Origins & Radiofarda).

Parthian Warrior Armed to the Teeth

Situated in the Alborz mountains close to the ancient Hecatomopylos (“Hundred Gates”), today’s Damghan and Tepe Hissar archaeological sites dating back to the 5th millennium BC, the tiny village of Paji has a population of less than five hundred people. Two years ago during expansion work in the same ancient burial site, the skeleton of a young girl was discovered buried in an earthenware jar with bronze necklaces and bangles, which dated back 5000 years.

Part of the sword, skeletal remains and the earthen vessel found in the Parthian warrior’s grave (Source: Tehran Times).

Historian Mehdi Izadi was present at the funeral of the COVID-19 victim, and he told Radio Farda that “...parts of a skeleton, a sword, a quiver and arrows, a dagger, a shield and an earthen vessel” were unearthed, dating back to the Parthian (Arsacid) period, which suggests this was the skeleton of a Parthian warrior. Note that the Parthian site of Vestemin in Mazandaran has yielded (in 2015) a large number of complete and intact skeletons with a very large number of (intact) weapons:

Parthian sword discovered with a skeleton and other artifacts during COVID-19 burial in Iran (Source: Radio Farda).

An Ancient and Broad Reaching Empire

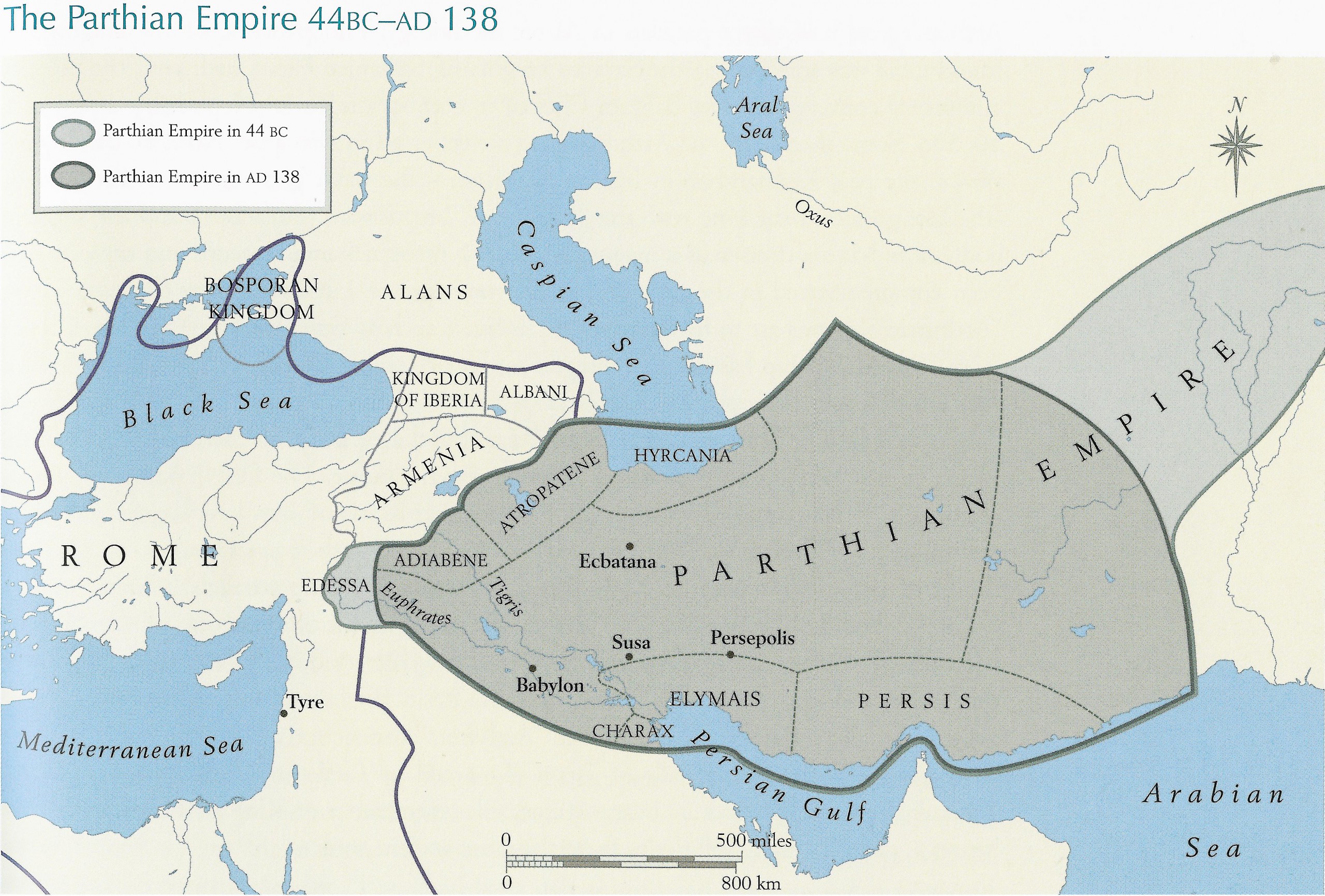

The Parthian Empire, also known as the Arsacid Empire, was a major political and cultural power in ancient Iran between 247 BC 224 AD, named after ‘Arsaces I’, the esteemed military leader who founded the Parni tribe in the mid-3rd century BC after conquering the region of Parthia. Located on the Silk Road trade route between the Roman Empire in the Mediterranean and the Han Dynasty of China, the subsequent Parthian Empire stretched from what is now central-eastern Turkey to eastern Iran.

[Click to Enlarge] Map of the Parthian Empire in 44 BCE to 138 CE (Picture source: Farrokh, page 155, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

Parthian art, architecture, religious beliefs and cultural traditions held elements of ancient Greek, Persian, Hellenistic, and regional cultures, and with the expansion of Arsacid power, their central government shifted from the city of Nisa to Ctesiphon, located along the Tigris to the south of modern Baghdad, Iraq.

A Feared and Respected Mounted Cavalry

The Parthian army was mainly composed of nobles (Azat) and their subjects, but also paid mercenaries at times of war, and Shahbazi, A. Shapur’s entry, ‘ Army i. Pre-Islamic Iran ’, in the 1986 Encyclopaedia Iranica, says Parthian generals were renowned for finishing expeditions as quickly as possible, so the nobles could get back to their estates and crops. Parthian forces consisted of two main types of cavalry; the cataphracts, a mounted force wearing heavy-mail armor and the second component was mounted archers, a much lighter and more mobile cavalry who used composite bows to shoot at enemies while riding and facing the opposite direction.

Reconstruction by Peter Wilcox and the late historical artist, Angus McBride of Parthian armored knights as they would have appeared in 54 BCE (Picture Source: Osprey Publishing).

As noted by Guisto Traina in his text (2010 & 2011) book “Carrhes-Anatomie d’une Défaite: Quand L’Orient humilia Rome [Carrhae-Anatomy of a Defeat: When the Orient humiliates Rome]. Published by Les Belles Lettres (first published 2010)“ Rome had learned that the Parthian Spad (army) of Persia was more than capable of blocking the Romans from expanding eastwards to India and China.

A historical video of the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BCE (Source: Kings & Generals in YouTube).

Kill Shots of the Easy Riders

Regarding this tactic, the Ancient Encyclopedia tells us that mounted Parthian warriors:

“…whirled about their horse during military engagement – to attack the flank of pursuing cavalry, to change direction to help fellow warriors, or to have the advantage of maneuverability during one-on-one combat with enemy cavalry.”

Parthian Horse archers engage the Roman legions of Marcus Lucinius Crassus at Carrhae in 53 BCE. Unlike the Achaemenid-Greek wars where Achaemenid arrows were unable to penetrate Hellenic shields and armor, Parthian archery was now able to penetrate the armor and shields of their Roman opponents (Picture Source: Antony Karasulas & Angus McBride).

Strabo also mentions the other part to the Parthian horseman’s military superiority was their “ease in speedy traveling” (3.5.15) helping the archers deliver constant kill shots at full gallop but also meaning the riders weren’t worn out from riding a choppy gaited horse.

The skeleton discovered in the village of Paji didn’t have a compound bow or plate armor, but he did have a sword, and if it was a functional weapon and not ceremonial or ritual addition to the man’s grave, it suggests he once belonged to the Parthian infantry, who were relatively small in numbers, but their roles were no less important as they were primarily employed as frontline guards tasked with protecting Parthian forts.