The Great Wall of China is well known as the largest wall in Asia (or indeed the world). Less known is the Wall of Gorgan in northeastern Iran (specifically the plain of Gorgan) attributed to the Sassanian era (224-651 AD). The structure is yet another testament to Sassanian engineering capabilities.

According to the Science Daily News (February 26, 2008) the Wall of Gorgan is::

“…more than 1000 years older than the Great Wall of China, and longer than Hadrian’s Wall and the Antonine Wall put together.”

The Science Daily report is significant as it was generally believed that the Gorgan Wall and Wall of China had been been built around the time of the Parthian dynasty. The Parhtian origin hypothesis had been postulated by Dr. Kiani in 1917 (see further below).

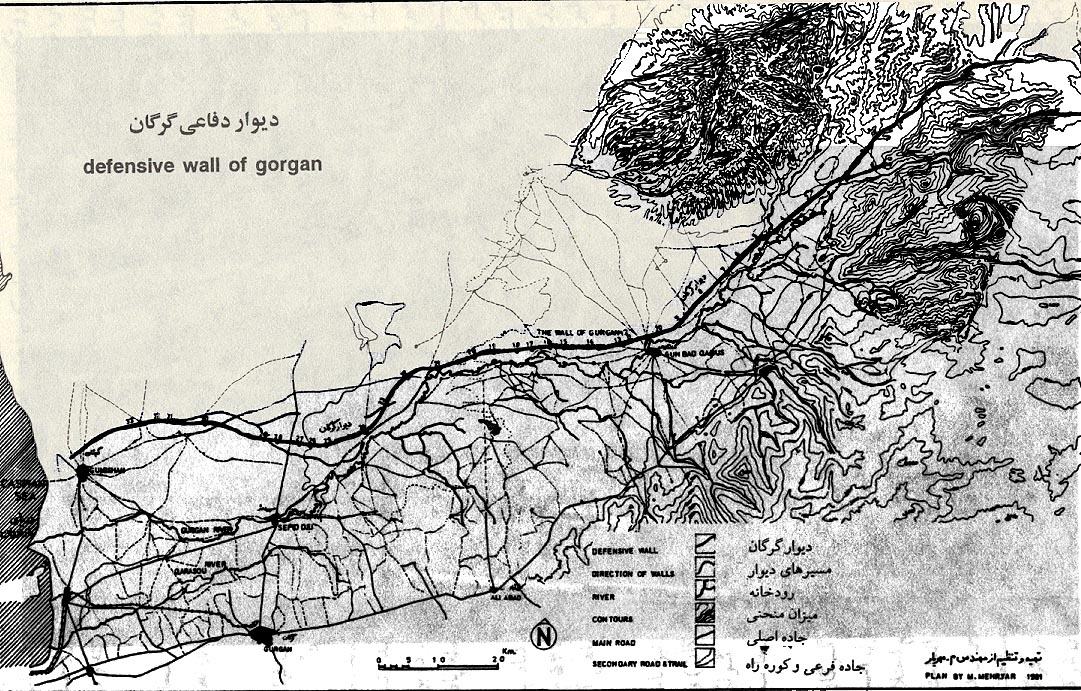

The Great Wall of Gorgan is the world’s largest defense wall, second only to the famed Wall of China. The Gorgan Wall measures approximately at a length of 155 kilometers and spans a range of 6-10 meters in width. The Gorgan Wall begins from the coast of the Caspian Sea, meandering to the north of Gonbade Kâvous. The Gorgan Wall stretches to the northwest and terminates to the rear of mountains of Piškamar.

An Iranian map of the Gorgan wall. The works of Dr. Kiani in 1971 were invaluable in helping lay the basis of mapping the structure. The Gorgan Wall is second only to the Great Wall of China in length.

Before examing the Gorgan Wall, we briefly examine the territory, etymyology and settlements of the ancient Iranian province of Gorgan.

The Territory, Terminology and ancient Cities of Gorgan

The Gorgân Wall is known by numerous names. Some of these include the Dam of Anushirvan, the Dam of Alexander, the Dam of Firuz and Qizil Yilan.

The inhabitants of this region are generally believed to have been the ancient Hyrcanians. Gorgan itself is one of Iran’s most ancient regions and is situated just to the Caspian Sea’s southeast. Gorgan has been a part of the Median, Achaemenid (559-333 BC), Seleucid, Parthian (247 BC-224 AD) and Sassanian empires in the pre-Islamic era. The term Gorgan is derived from Old Iranian VARKANA (lit. The Land of the Wolf). Interesitngly the term Gorgan linguistically corresponds to modern Persian’s “Gorg-an” or “The Wolves”.

The capital of ancient Gorgan was known as Zadrakarta, which later became Astarabad. This city can be traced back to at least the Achaemenid era. Another historical city of importance was ancient Jorjan.

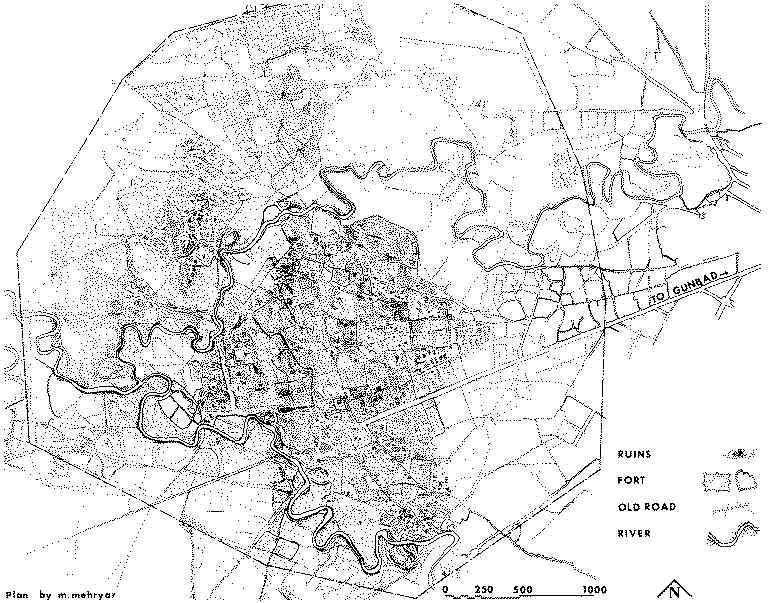

An aerial map of ancient Jorjan or Gorgan by Dr. Kiani.

The Gorgan Wall and the Savaran

The first serious expedition to the site occurred in 1971 by an archaeological team led by Dr. Kiani. The second thorough analysis of the structure was made by an archaeological survey team in the 1990s. This was part of the activieities related to the development of the Golestân Dam. The most recent expedition occurred in early 2008 by an international archaeological team composed of specialists from Iran and England (the Universities of Edinburgh and Durham).

An excavation team at the Gorgan Wall. The most recent expeditions have been conducted by an Iranian-British team in late 2007-early 2008.

The Sassanian dynastry continued to construct, improve and fortify the site. What was unique in the Partho-Sassanian system was the construction of castles along the wall at predetermined distances. The shortest distance between the castles was 10 kilometers with the longest being 50 kilometers. It is noteworthy that all of these were supported by an aqueduct and various water channels.

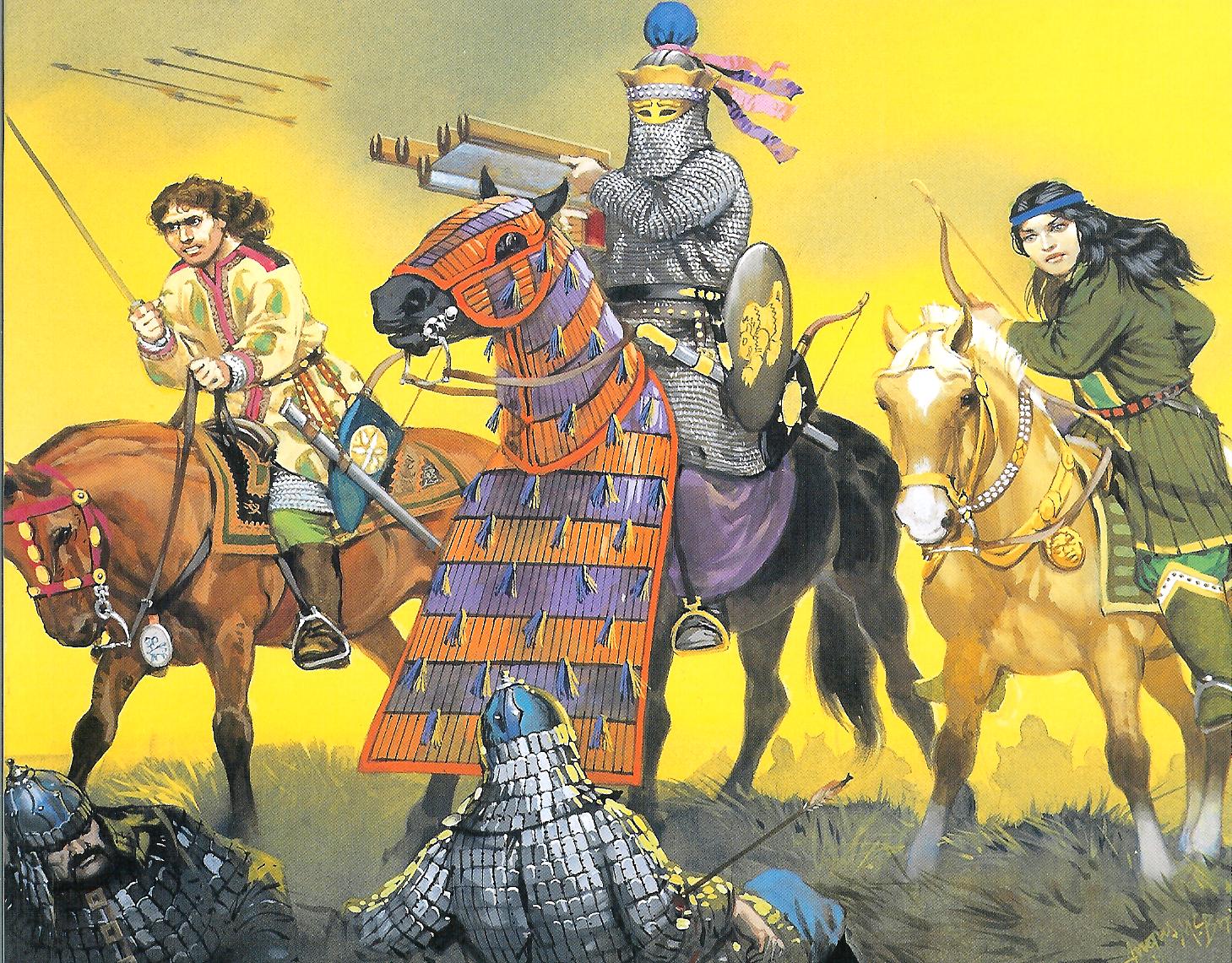

The majority of these fortresses are of the square-shape type and had barrack-type buildings that could house up to 30-36,000 Savaran (Sassanian Elite cavalry). Up to forty of these castles have been identified thus far. The Savaran of the Sassanian Gund (Army) were a highly trained and effective force, who more than made up for their small numbers with rigorous training and military effectiveness. They were able to rapidly deploy to threatened sectors of the Sassanian kingdom, and the system of castle-networks was highly integral in the basing and deployment of the Savaran. Castle-systems were in evidence in the Caucasus as well as the western frontier against the formidable Romano-Byzantines.

An aerial view of a portion of the wall of Gorgan (Courtesy of Iran Review Website). The Savaran (Elite Sassanian Cavalry) units were housed in a system of fortresses that guarded nearly 200 kilometers of ancient Iran’s northeastern frontiers.

An aerial view of a portion of the wall of Gorgan (Courtesy of Iran Review Website). The Savaran (Elite Sassanian Cavalry) units were housed in a system of fortresses that guarded nearly 200 kilometers of ancient Iran’s northeastern frontiers.

The system of castles was developed by the Sassanians into a system of fluid defense. This meant that the Gorgan Wall was not part of a purely static system of defense. The main emphasis was in a system of fluid defense-attack system. This entailed holding off potential invaders along the line and in the event of a breakthrough, the Sassanian high command would first observe the strength and direction of the invading forces. Then the elite Sassanian cavalry (the Savaran) would be deployed out of the castles closest to the invading force. The invaders would then be trapped behind Iranian lines with the Gorgan Wall to their north and the Savaran attacking at their van and flanks. It was essentially this system of defense that allowed Sassanian Persia to defeat the menacing Hun-Hephthalite invasions of the 6-7th centuries AD.

The Savaran counterattacking against invading Hun-Hephthalites in northeast Persia. The Sassanian High Command often channeled invading forces into “kill zones” and destroyed them by deploying Savaran units from castles along the Gorgan wall and other areas further east. The figure to the left is a Kushan warrior wielding the large east-Iranian straight two-edged swords. The central warrior (with armor and mail) is derived from the figure of Khosrow II and his steed Sabdiz at Tagh-e-Bostan in Kermanshah, western Iran. The right figure is a female warrior who is a local governess (Paygospanan-Banu). (Farrokh, 2005, pp.41-42, 53-54, Plate C).

As noted previously, the width of the Gorgan wall varies from 6 to 10 meters along its length. The wall’s thickness varied due to the varied geographical characteristics (climate, soil, terrain, etc.) of each region traversed by the structure.

There is little doubt that the Partho-Sassanians were endowed with a high level of engineering proficiency. As noted by a report by the Science Daily on February 26, 2008:

New discoveries unearthed at an ancient frontier wall in Iran provide compelling evidence that the Persians matched the Romans for military might and engineering prowess.

One of the views of the engineering works of the Gorgan Wall Courtesy of Yataahoo Website). . Iranian engineering skills were on par with those of Rome, China and India. Many of the structures of the Gorgan Wall have stood the test of time.

Post-Islamic Era

The city of Jorjan survived into post-Islamic times. when it acquired a high status in post-Islamic times (especially during the 9th century) but fell into decline and was obliterated by the Mongols by the 13th century. Gorgan had became a major venue for the inroads of Oghuz-Turkic tribes into Iran from the 11th century AD.

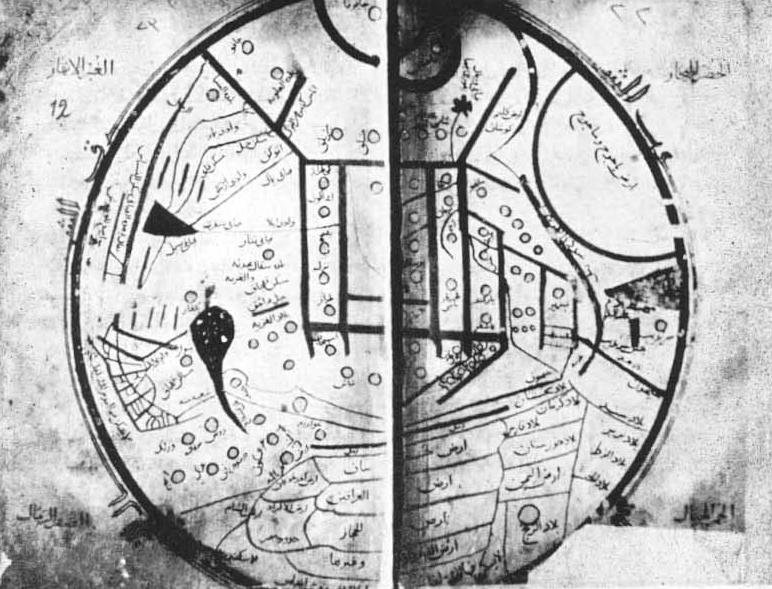

The Wall of Gorgan as depicted in a 15th century AD manuscript (Nasr, 1976, Plate 19).

The city of Astarabad (or ancient Zadrakarta) also survived into post-Islamic times. By the time of Nader Shah ( 1688-1747), a powerful defense wall had been constructed for protection against nomadic Turkmen raids. By the eve of the Qajar dynasty in the late 1700s had become a major bastion against Turkmen inroads into Iran;s northeast (along the Caspian). By late Qajar times the term “Gorgan” was used to designate the town of Astarabad. Gorgan grew rapidly into a thriving urban center during the 20th century.

Locals in modern Gorgan amuse themselves in the snow (Photo by Ebrahim Asghari).

As reported by the CHN news agency of Iran on November 14, 2006, the Great Wall of Gorgan has been nominated for UNESCO status.

Further Readings

Farrokh, K. (2005). Sassanian Elite Cavalry 224-651 AD. Oxford: Osprey Publications.

Kiani, M.Y. (1982). The Gurgan Plain. Archäologische Mitteilungen aus Iran. Ergänzungsband 9. Berlin. See also Gorgan IV Archaeology. Encyclopedia Iranica.

Nasr, S.H. (1976). Islamic Science: An Illustrated Study. London: World of Islam Festival Trust.

Omrani Rekavandi, H., Sauer, E., Wilkinson, T. & Nokandeh, J. (2008). The Enigma of the Red Snake: Revealing one of the World’s greatest Frontier Walls. Current World Archaeology, Number 27, February-March, pp.12-22.