The article “When Roman “Barbarians” Met the Asian Enlightenment” was first published by The Strange Continent.com. A portion of that article has been printed below which has been edited. Commentaries have also been inserted for reference. Kindly note that the article printed below features a number of additional images and accompanying captions that do not appear in the original article in The Strange Continent.

Consistent with this topic, a lecture entitled “Civilizational Contacts between Ancient Iran and Europe during the Classical Era“ will be offered by Kaveh Farrokh at the University of British Columbia, Department of Asian Studies Alireza Ahmadian Lectures in Persian and Iranian Studies (November 29, 2019, 6:30-8:30, Room 120, CK Choi Building) … for further details kindly click the image below …

===========================================================================

This week, the BBC announced the discovery of two “ethnically Chinese” skeletons at an ancient Roman burial site in England. Who were they? What drove them to the far end of the world? We don’t know, yet.

But for once, an article’s clickbait headline may not be exaggerating. If the genetic identity of these skeletons can be confirmed, it could indeed “rewrite Roman history” — or at least, a whole lot of long-held assumptions about who was in contact with whom in the days of the Roman Empire.

Oh, we’ve known for a long time the ancient Romans were aware of China’s existence — in fact, Chinese silk was such a drain on the Roman economy that the senate tried to outlaw it in the year 14 CE. And the Chinese emperors of the Han dynasty were certainly aware of Rome — they called it Da Qin and repeatedly tried to reach it with envoys and missionaries.

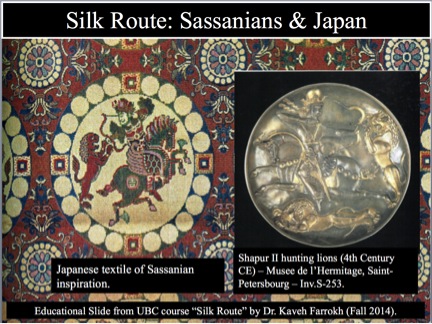

No one disputes the fact that these two cultures had centuries of indirect contact, via trade routes through India and Persia. Roman coins have been found as far east as Japan where Persians were teaching mathematics to the locals.

Sassanian influences upon Japanese arts: the case of the metalwork plate of Shapur II hunting lions (Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg – Inv. S-253) and motif-parallels in Japanese textile arts (Source: Fall 2014 course on the Silk Route at the University of British Columbia).

DNA evidence seems to suggest that Europeans settled on the western fringes of China as early as the 200s BCE.

COMMENT BY Kavehfarrokh.com: The sentence “Europeans settled on the western fringes of China as early as the 200s BCE” is somewhat misleading. First, there are common Indo-European ancestors for the Europeans, Indians and Iranians. The peoples the writer is referring to may have been variously proto-Iranian or Tocharian – the dress found among their mummies in Urumchi for example bear striking resemblance to the later attire of the Medes, Achaemenids, Scythians, Sarmatians, Parthians and Sassanians. Second, these settlements in northwest China appear to have taken place earlier before the reign of the Medes and the succeeding Medo-Achaemenids.

What’s much less clear, though, is whether Chinese or Roman diplomats ever managed to achieve direct contact on each others’ native soil.

Until these Chinese skeletons were unearthed in England — at the far-western end of the Roman Empire, no less — no one had ever found any proof that a single Chinese envoy ever made it to Rome; or that a Roman envoy reached China. Which would mean…Romans were largely locked out of the civilized world. But wait… wasn’t Rome “the civilized world?”

That’s certainly what most of us (in the West, anyway) are taught in school. Back in my school days, I was taught a fair amount about Rome, a tiny bit about China, even less about Persia, and nothing at all about the Kushans, or the Axumites, or any of the other powerful empires that controlled large chunks of the globe — and often helped shape the cultures and fortunes of European nations. Maybe you can relate.

The truth is, though, that Rome’s Asian contemporaries completely dwarfed Rome in many respects: heritage, population density, cultural diversity, technology, architecture, medicine, philosophy, poetry… I could go on, but you get the idea. During the Roman period, the Asian continent was by far the wealthiest, most advanced, most culturally diverse place on earth. Imperial Rome was a dim backwater by comparison.

Ever since I’ve learned that fact, it’s always made me sad to think of the Romans being largely cut off from the main action on the world stage.

If researchers can verify the ancestry of these skeletons in England, maybe Rome wasn’t quite as cut off as we always believed. It’s an exciting thought. But it doesn’t change the fact that, on the whole, contact between Rome and the East — and thus, between Eastern and Western cultural legacies — was mostly indirect, mediated by third (and often fourth and fifth) parties.

Who were these vast empires of Asia? What was it like to live in them? Where did they come from, and what legacies did they leave?

I’m glad you asked. Let’s take a journey to the East.

Before we begin our tale, we first need to briefly set our stage, and make sure all our actors are on their marks.

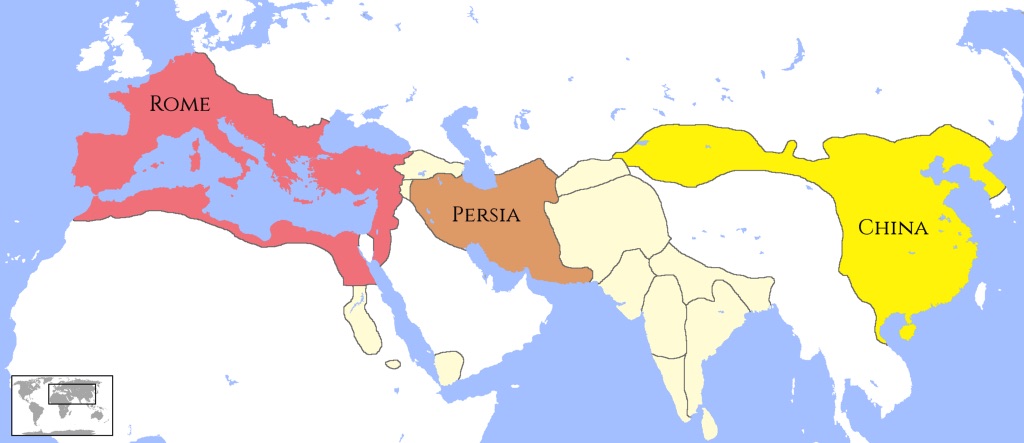

In the 200s to 400s CE (the range of dates during which the owners of those Chinese skeletons made their way to Roman Britain) the map looked something like this:

A map of the Three Great Empires of Antiquity in c. 200 CE: Rome, Persia (Parthians followed by Sassanians) and China (Source: The Strange Continent).

I say “something like this” because a lot was going on during those centuries:

- Rome’s legions were fighting fiercely for control of Gaul (modern France and Germany), Britain, Egypt, and various parts of the Balkans; while a succession of (often unfairly maligned) emperors scrambled to hold Rome together through an endless series of famines, wars with the East, coups d’état, refugee crises, and revolts.

- The steppe horsemen known as the Parthians lost control of Persia, which entered a great classical age under the Sassanian dynasty.

- The Han dynasty lost its grip on China, which split into three powerful warring kingdoms.

- Vast tracts of southern Asia were changing hands among a dozen or more competing empires, each with its own rich culture.

Since we don’t know exactly when those Chinese travelers (whoever they were) left China and arrived in Roman Britain, it’s hard to say exactly what kind of “China” they left, what kind of “Rome” they arrived in, or what kind of “Persia” — or what other empires, exactly — they had to pass through.

With that in mind, let’s spend some time in a few of those Asian empires, and get to know their people a little better.

The Sassanians

The Sassanians could trace their cultural ancestry all the way back to the primordial mists of recorded history, to the dawn of civilization itself.

Ancient Persian traditional music as posted by The Strange Continent.

They had taken Persia from the Parthians, who’d taken it from the Seleucids — descendants of Alexander; an infamous villain in Persian eyes to this day — who’d ripped it from the hands of the glorious Achaemenid dynasty, who’d freed Mesopotamia from the brutal yoke of the Assyrian Empire, back when Rome was an unknown village.

The Assyrians, of course, had been just the latest in a line of conquerors reaching back through the Babylonians, though many long centuries, to the Akkadian Empire of Sargon the Great — the first documented multi-ethnic empire in world history, which owed its own cultural legacy, in large part, to the Sumerians.

Sargon of Akkad, circa 2250 BCE (The Strange Continent).

By the time they met Rome, the Sasanians could look back through no less than 3,000 years of literate, urban society. The oldest works of poetry and sculpture in their treasure-houses were as ancient, for them, as the Iliad and the Odyssey, or the Old Testament, are for us today.

In fact, Babylon had long ago been ruled by yet another dynasty from the Persian region. The Elamite people, whose own literate culture was as ancient and venerable as that of the Sumerians, had conquered large swathes of Mesopotamia in the 1800s BCE, holding dominion until they were thrown out by an invading king called Hammurabi.

A bust of Sassanian Shahanshah Shapur II (The Strange Continent).

At its height, the Sassanian Empire spanned all of today’s Iran, Iraq, Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatif, Qatar, UAE, Syria, Palestine, Lebanon, Israel, Jordan, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Dagestan, South Ossetia, Abkhazia, Egypt, large parts of Turkey, Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Yemen and Pakistan. It was geographically smaller than the peak-size Roman Empire— but it was more urban, and far more densely populated.

The Sassanian Empire at its greatest extent c. 620 CE, under Shahanshah Khosrau II (The Strange Continent).

The Sassanian Empire’s subjects hailed from uncounted hundreds of tribes and peoples. They practiced at least ten different major religions, including Judaism, Hinduism and Buddhism; along with a late, decadent form of the religion of ancient Babylon.

The state religion, however, was Zoroastrianism — as it had been since the Achaemenid dynasty, five centuries before, and would remain until the coming of Islam (while many practicing Zoroastrians still live in the region, and around the world, today).

Though the empire’s people spoke dozens of languages, the tongues of the court were Greek and Aramaic, along with an ancestor of the Farsi language now spoken in Iran.

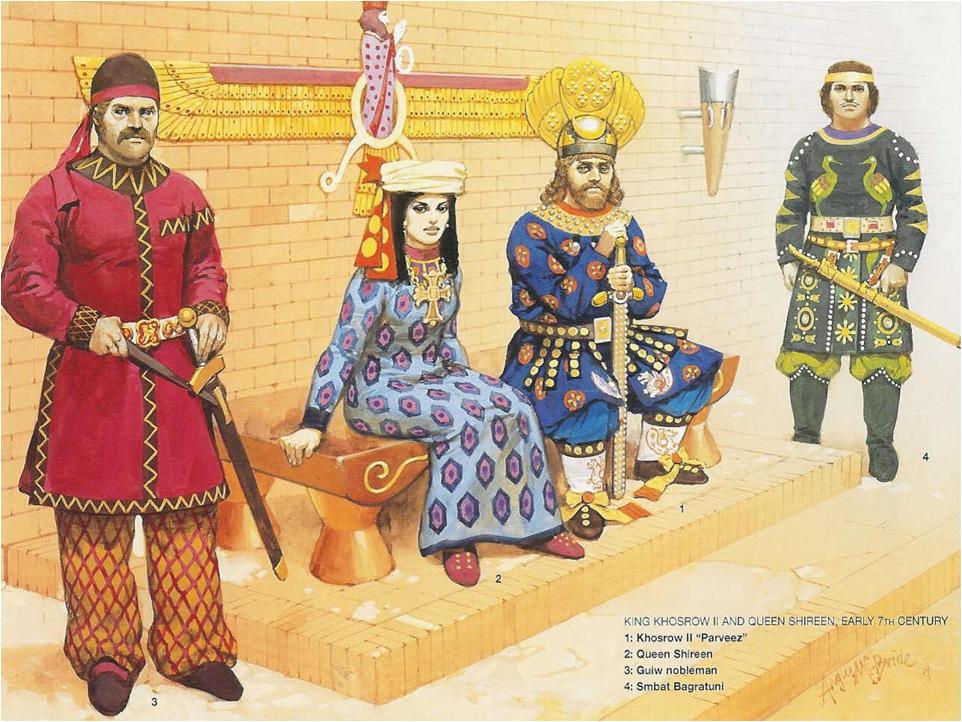

At the head of the Sassanian state sat the shah-en-shah — the King of Kings, a title borrowed from the Achaemenid Persian emperors like Darius and Xerxes.

Below the shah-en-shah, a meticulously organized pyramid of governors and viziers extended down to the powerful nobility of land-holding feudal aristocrats, who oversaw the middle castes of priests, warriors, commoners, and artisans.

Court of Khosrow II and his queen Shirin – Smbat Bagratuini (Figure 4) was to replicate the spectacular successes of the Sassanian military against a renewed Turco-Hephthalite invasion of the Sassanian empire from the northeast in 618-619 CE (For more information on color plates and sources consult: Plate F, pp.53-54, 62, Elite Sassanian Cavalry-اسواران ساسانی-).

The upper classes enjoyed the first recognizably “Persian” culture: brocaded silks, floral tapestries, ornate goblets, sumptuous carpets, intricate mosaics, and the styles of music, food and poetry that would so captivate their Islamic conquerors a few centuries hence — just as they would later captivate the Seljuks, the Mongols and the Ottomans; and that continue to lend their distinct influences to Turkish and Iranian culture, even today. Any time you savor a bite of baklava or sip a glass of dark tea, thank the Sassanians.

Sassanian influence remains strong in this painting of King Bahram V Gur, from the mid-16th-century Safavid era (The Strange Continent).

You can also thank the Sassanian aristocracy for much of (what would later become) the medieval European aesthetic. Look at this Sasanian rock engraving, for example, and you’re essentially looking at a medieval European king …

Rock-face relief at Naqsh-e Rustam of Sassanian emperor Shapur I (on horseback) capturing Roman emperor Valerian (standing) and Philip the Arab (kneeling), suing for peace, following the victory at Edessa (The Strange Continent).

…except that this engraving depicts the Sassanian shah-en-shah Shapur I, and dates from around 260 CE — a full thousand years before the European medieval period, when the height of Roman fashion was still togas and sandals. It’s like Shapur time-traveled to Rome from the future.

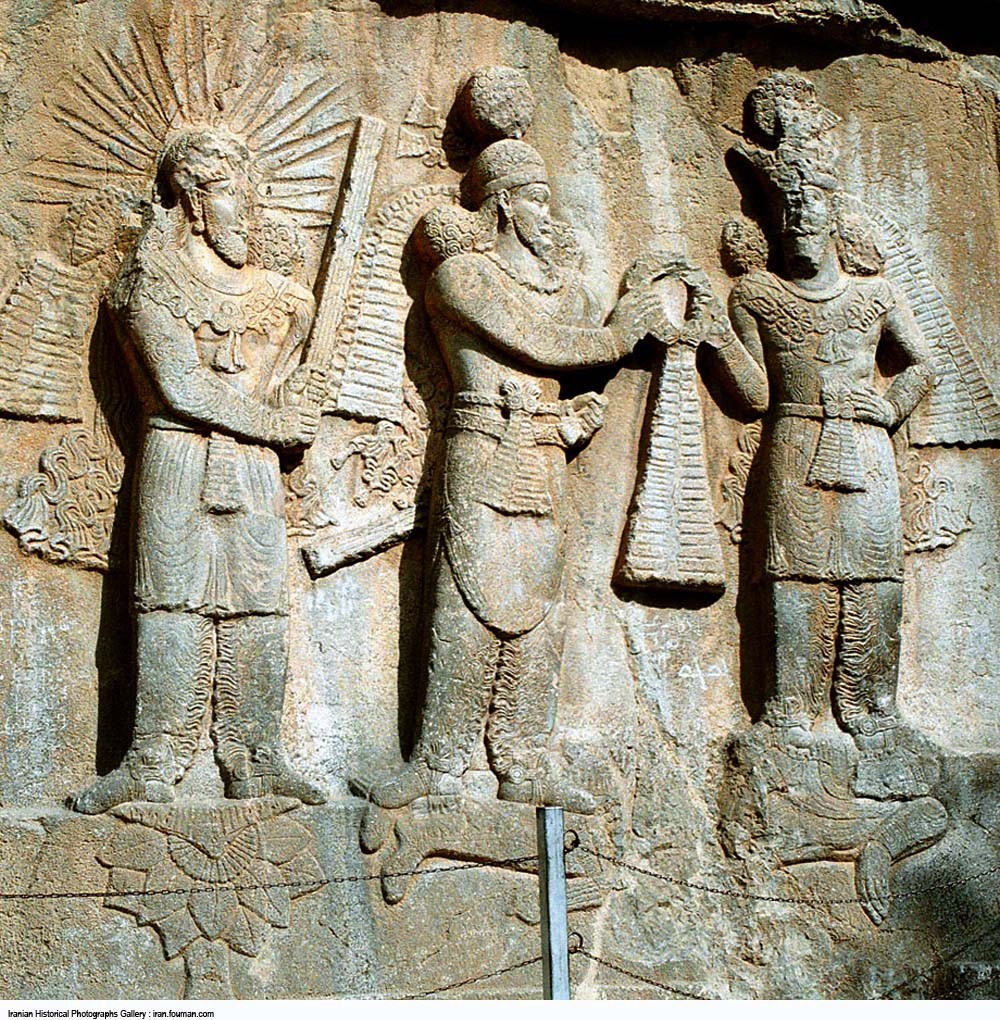

Regal Sassanian figures (middle and right) with the ray-headed Mithras holding a ceremonial sword or barsom at Taghe Bostan (The Strange Continent).

The Sassanian aristocracy, like their later medieval imitators, wore ankle-length robes and pointed slippers, tunics and trousers— more borrowings from the Achaemenids, Assyrians and Babylonians before them.

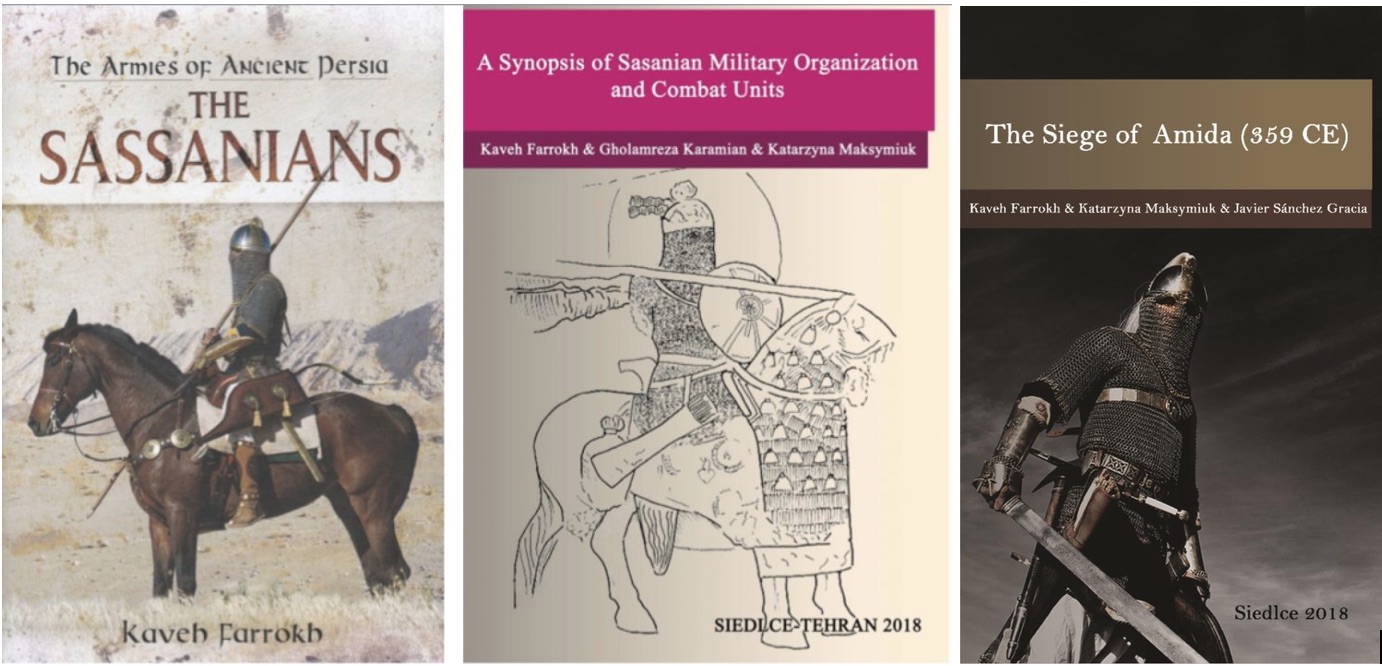

They rode into battle on famously enormous horses, outfitted in full suits of chain-mail armor, wielding broadswords and longbows, carrying jousting lances. For more see:

- Kaveh Farrokh, Katarzyna Maksymiuk, Javier Sánchez Gracia, The Siege of Amida (359 CE), Siedlce 2018.

- Kaveh Farrokh, Gholamreza Karamian, Katarzyna Maksymiuk, A Synopsis of Sasanian Military Organization and Combat Units, Siedlce-Tehran 2018.

- Gabriel, R. A. (2018). Military History Journal, Book Review: The Armies of Ancient Persia-The Sassanians.

- Farrokh, K. (2014). Soldiers of the Sassanian Empire: Rome’s unbeaten rival in the East. Military History, November Issue 50, pp.62-66, 68.

Ever wondered how Roman legions would fare against medieval knights? You don’t have to wonder — the Romans fought hundreds of battles against the Sassanians, and the Sassanians often beat the Roman legions to a bloody pulp; especially when fighting on the defensive.

When the Roman army started incorporating their own armored heavy cavalry, they got better at fighting back against the feudal knights of the Sassanian aristocracy — but the Romans never made any permanent incursions into Sassanian territory, or inflicted many serious defeats. The Sassanians never made it very far into Roman territory, either. For hundreds of years, the two armies held each other, in large part, at a stalemate.

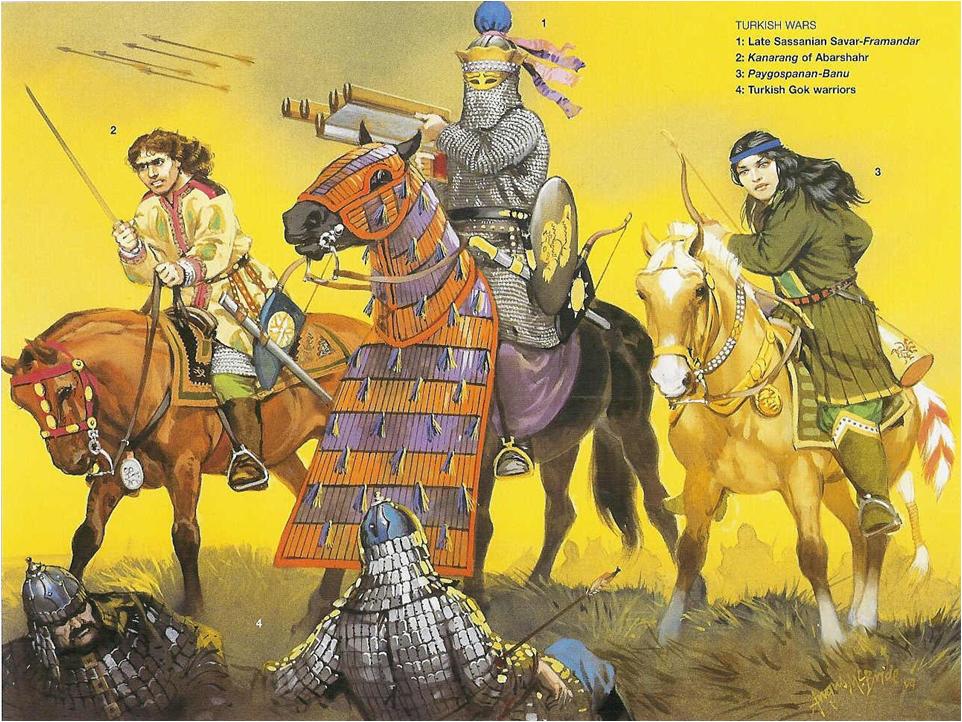

Sassanian forces counterattack the invading Turco-Hephthalites in the Sassanian Empire’s northeast; the figures in the above plate (1-late Sassanian Savar-Framandar, 2-Kanarang, 3-Paygospan and 4-Turkic Gok warriors) are based on reconstructions from Sassanian archaeological data such as the grotto of the armored knight inside the vault or Iwan at Taghe Bostan, the (post-Sassanian) metalwork work plate of Pur-e Vahman as well as East Iranian sources (For more information consult: Plate C, pp.53-54, 60-61, Elite Sassanian Cavalry-اسواران ساسانی-).

It wasn’t only in military matters that the were centuries ahead of their time. Their scholars translated the works of Plato and Aristotle — preserving many books that were later lost to the West — and organized debates between sages and scholars of dozens of philosophies and religions, from all across Asia.

The shah established a “Grand School” at the capital city of Ctesiphon (in modern Iraq), where more than 30,000 pupils studied astronomy, architecture, medicine and literature. In fact, a few centuries later, when the Roman emperor Justinian forcibly closed all the Greek schools, the Sassanians would welcome the fleeing Greek philosophers with open arms.

A detail of the painting “School of Athens” by Raphael 1509 CE (Source: Zoroastrian Astrology Blogspot). Raphael has provided his artistic impression of Zoroaster (with beard-holding a celestial sphere) conversing with Ptolemy (c. 90-168 CE) (with his back to viewer) and holding a sphere of the earth. Note that contrary to Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” paradigm, the “East” represented by Zoroaster, is in dialogue with the “West”, represented by Ptolemy. Prior to the rise of Eurocentricism in the 19th century (especially after the 1850s), ancient Persia was viewed positively by the Europeans. For more see Ken R. Vincent: Zoroaster-the First Universalist …

Long after the Western Roman Empire fell beneath waves of attack from the Huns and Goths, the Sassanian emperors continued to hold their own against the Eastern Roman Empire, slowly growing weaker under relentless losses against the Byzantines, the Turks, the Khazars, and hordes of other enemies.

By the time the armies of Islam rode out of Arabia, the once-great Sassanian Empire was fragmented and exhausted. An army led by Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattāb captured city after Sassanian city throughout the mid-600s; and by 651, the remains of the knightly and priestly aristocracy fled, in despair, into the vastness of the Central Asian steppe-land.

The remains of the Sassanian royal palace at Ctesiphon, in modern Iraq (The Strange Continent).

It’s often been said, though, that no one truly captures Persia. Instead, Persia captures her conquerors. There’s no doubt that she captured the Arabs. Much of what we think of as “Arabian culture” today — the distinctive styles of art, food, architecture and music; the tales of The 1,001 Nights; the wealth and opulence of Middle-Eastern monarchs— owes far more, in fact, to the Sassanian palace gardens than to the deserts of Arabia.

To read more on this topic, consult The Strange Continent …