The article “Ancient Roots of Iran’s Wrestling and Weightlifting Olympic Dominance” was written by Max Fisher for The Atlantic (August 9, 2012).

Kindly note that: (a) the text printed below has been edited from the original The Atlantic report and (b) the images and accompanying captions printed below do no appear in the original The Atlantic report.

===========================================================================

Centuries before the 20th century and notably before the Islamic invasions of ancient Iran, Persian athletes fused spirituality and strength training in a practice called Varzesh-e-Bastani, the legacy of which may still persist. Freestyle wrestling is often described as the “first sport” of Iran, according to U.S.-based Iranian historian Houchang Chehabi. Iran excels at international wrestling competitions, winning three gold medals the 2012 Olympics alone, and an astounding 35 medals in 1948-2012. But the story of how Iran came to so dominate wrestling is older than contemporary times, possibly older than even Islam itself, and may have to do with an Iranian understanding of the sport far different than the West’s.

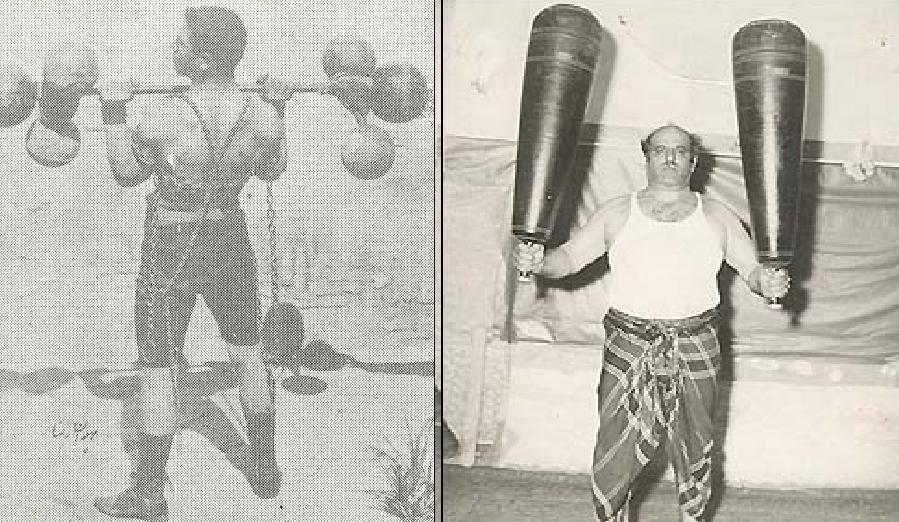

Depiction of ancient exercise routines and equipment from the late Sassanian era (Source: Zurkhaneh Review, No.2, July 2011, pp.14-15; above item currently stored in the British Museum (number: 1849,0623.41). Note the “meel”-type weight-handle held by upright person at left and the – held by the arms of the person lying down; note that he is simultaneously pressing some type of “eights” with his feet. The author of the Encyclopedia Iranica article, Houchang E. Chehabi, states later below in his article that “The fact remains that there is no textual or architectural evidence for the existence of zur-ḵānas before Safavid times (Elāhi). The idea of a pre-Islamic origin, however, lives on in popular writing.” While true that the specific term “Zur-Kāna” is not seen with the Classical and other ancient pre-Islamic sources, Chehabi’s suggestion of no evidence is questionable: the above ancient depiction provides clear evidence that the Zur-Kana exercises and exercise equipment were not spontaneously invented during the post-Islamic era. The British Museum however claims that the above item represents “…jugglers and an onlooker in oriental dress“. As noted already, the challenge with this interpretation is that the equipment in the above depiction (a) parallels contemporary Zur-Kāna training equipment too closely and (b) the routines shown by the above figures are too similar to contemporary Zur-Kāna training methods. However, little academic works have investigated the linkage between sports training in Iran’s pre and post-Islamic eras.

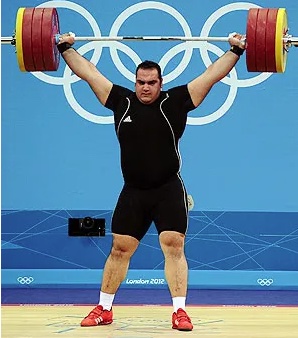

That story may also have to do with Iran’s record at weightlifting and, to a lesser extent, tae kwon do. Iranian weighlifters won the men’s super-heavyweight gold and silver this year, the former to the amazing Behdad Salimikordasiabi for lifting 545 pounds, more than a baby grand piano, over his head. He broke his own world record, which he’d set the year before in Paris, when he broke the previous record, also held by an Iranian. Though Iranians don’t win as many Olympic medals in tae kwon do, both men and women are perennial winners at other international and Asian leagues. Iran’s record in these three sports is even more striking compared to its abysmal Olympic record in everything else; in Olympics history, the country has only one medal from any other sport: a silver in discus throwing, won this Tuesday.

Iran’s Behdad Salimikordasiabi seizes the Olympic gold medal in 2012 and sets a new world record by lifting 545 pounds over his head (Source: SI.com). The weight which Salimikordasiabi whisked over his head is the equivalent of a Canadian moose (approx. 1000+ pounds) or baby piano.

The surprisingly rich academic literature on Iran’s impressive records at wrestling, weightlifting, and tae kwon do consistently connects all three to an ancient Persian sport called Varzesh-e-Bastani, which literally translates to “ancient sport.” To Westerners, Varzesh-e-Bastani might look like an odd combination of wrestling, strength training, and meditation. Though there’s no known link between Varzesh-e-Bastani and yoga, it might help to think of it as something like a Persian version of this athletic practice that’s also a method of personal and community development — and a symbol of cultural heritage.

Mil exercise ritual conducted in Tehran’s Namjoo Zurkhaneh (Source: Reza Dehshiri in Public Domain).

Though Western cultures typically treat wrestling as an aggressive, individualistic, and deeply competitive sport, traditional Persian Varzesh-e-Bastani, emphasizes it as a means of promoting inner strength through outer strength in a process meant to cultivate what we might call chivalry. The ideal practitioner is meant to embody such moral traits as kindness and humility and to defend the community against sinfulness and external threats. The connection of weightlifting with character development might sound odd, but it’s perhaps not so different from, for example, the yogic practice of Shavanasa, a meditative pose meant to bolster the spiritual and mental role of yoga’s stretches and poses.

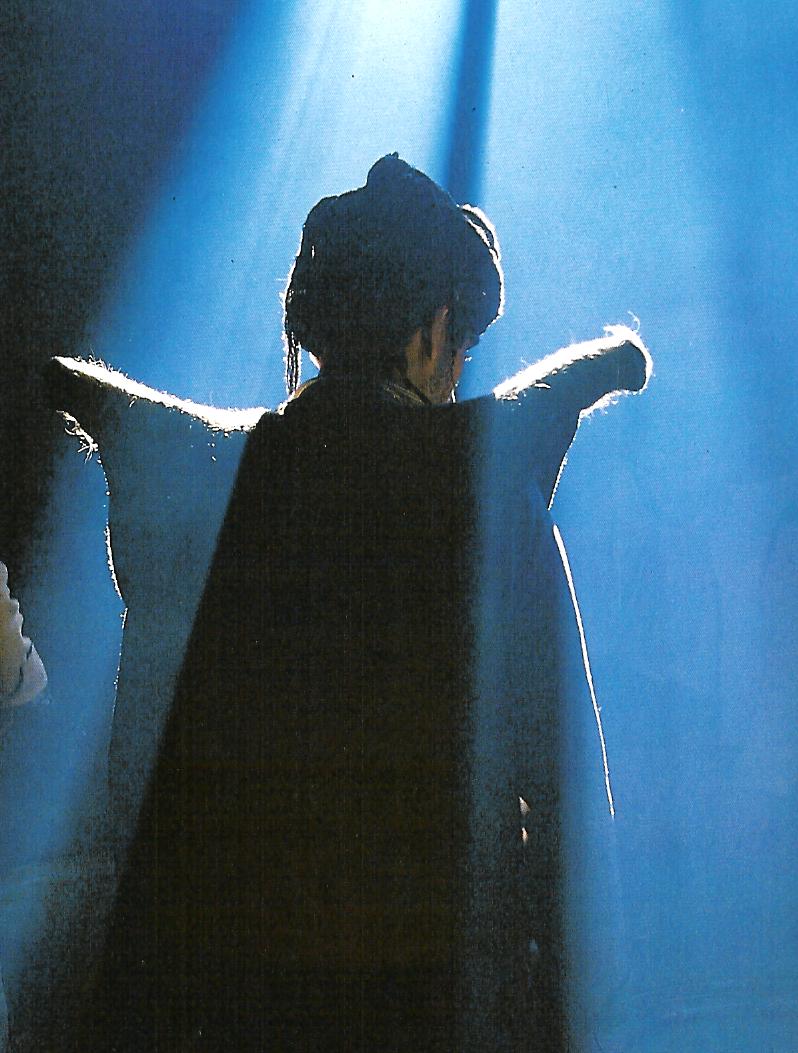

Varzesh-e-Bastani is traditionally practiced in a building called a Zoorkhaneh, which means “home of strength” and is often built and decorated in an ancient style that’s led archaeologists to trace them to the Mithraic era of the first through fourth centuries, AD. The Mithraic religion, named for the Persian god Mithra, spread through much of the Roman Empire before being displaced by Christianity — and, much later, displaced by Islam in Persia itself. But some Mithraic ideas and practices persisted in the Zoorkhaneh, and can maybe still be heard in the pre-exercise chanting or seen in the ritual movements.

Kurdish man engaged in the worship of Mithras in a Pir’s (mystical leader/master) sanctuary which acts as a Mithraic temple (Source: Kasraian & Arshi, 1993, Plate 80). Note how he stands below an opening allowing for the “shining of the light”, almost exactly as seen with the statue in Ostia, Italy. These particular Kurds are said to pay homage to Mithras three times a day.

History is political in Iran, and has been for centuries. Its leaders have alternatively embraced or downplayed the country’s ancient, pre-Islamic roots. After the Arab Muslim invasion, Persian elites resisted the new religion for centuries, seeing it as the Arabs’ religion. In the 1500s, though followers of Islam’s two major schools of Shi’ism and Sunnism had long been dispersed across the Middle East, Persia’s imperial Safavid rulers played up Iran’s Shi’a heritage as a way to unifying Arab Shi’a against the increasingly Sunni Ottoman Empire. The following migrations of Shi’a to Iran and present-day Iraq helped create a geographic division that largely holds to this day. Through these turbulent back-and-forths, leaders and popular movements alike have pushed away one aspect of Persian cultural heritage in order to lift up another, re-re-inventing their society so many times over that few institutions have survived intact. Even the Supreme Leader’s Islam does not always look so much like the Shi’ism of earlier generations.

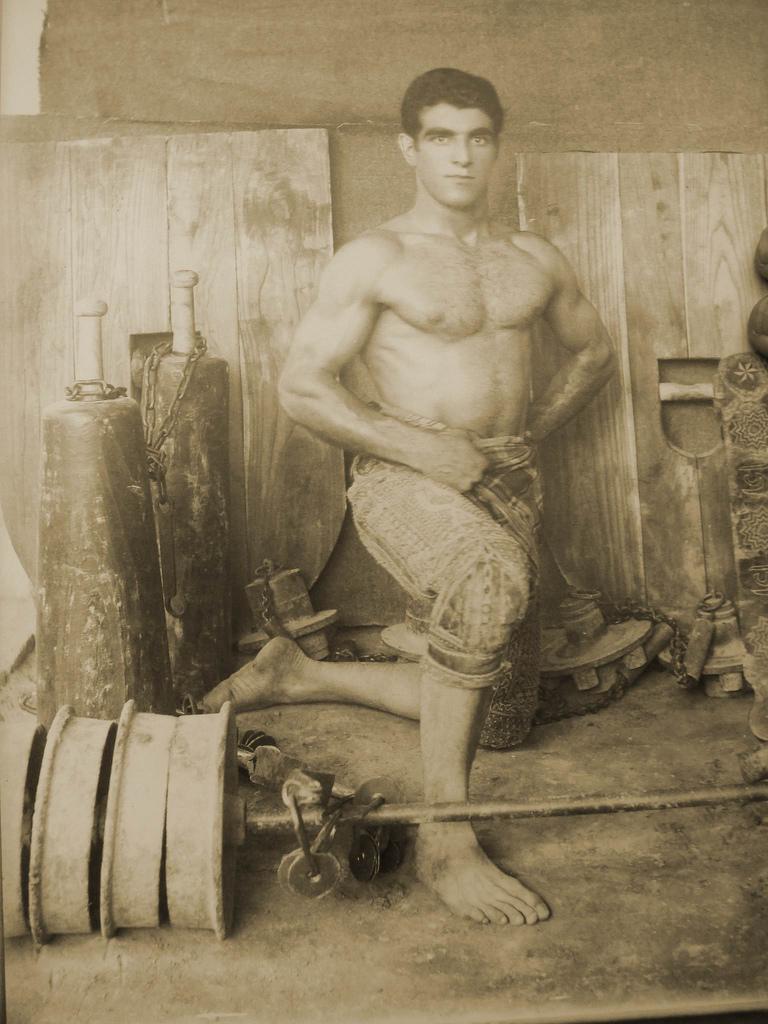

The Sang Gereftan (lit. stone grasping) where the Pahlavan athlete lies down on the ground to press up and down two Sang (which in practice are two metal shields, with each weighing 80 kilograms) (Image source: Ferdowsi Hotel Blog).

Yet, somehow, the Varzesh-e-Bastani traditions and the Zoorkhaneh have survived, embraced during both the shah’s secular Westernizing era and under the Islamic Republic as a symbol of Persian national pride and of cultural roots. Both regimes, though they couldn’t be more different, promoted the Zoorkhaneh and entrenched its practices into national physical education, even reminding Iranians that the sport’s champions had once defended their communities against the Mongol invaders of a thousand years earlier.

Iranian wrestler of 1920s training with traditional strength-training equipment (Source: Farsizaban). In the background to the left can be seen two upright Zoorkhaneh (House of Power) Meels with handles designed for increasing the strength and stamina of the arms. While Classical sources do not cite the term “Zur-Khaneh” or “Zur-Kāna” by name, the same sources report of the hard training experienced by the armies of the Sassanians.

Iranian nationalism and national pride — of a kind that seems possibly even broader than that of the supreme leader’s Islamist nationalism — has become tightly wound with international wrestling and weightlifting competitions, the two sports most closely associated with Varzesh-e-Bastani. In 1989, just after the end of the devastating eight-year war against Iraq, Iranian heavyweight wrestler Ali-Reza Soleimani defeated an American wrestler for the world wrestling championship that year, exciting Iranians who badly needed something to feel good about, and striking a symbolic (for them) blow against the U.S., which had aided the Baathist regime of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein in the war. State funding for wrestling immediately increased, and the Islamic Republic played up its ancient Persian roots to try and cash in on the popularity.

Members of the Turkish Zurkhaneh team at the 3rd Zurkhaneh Sports Men Championship of Europe May 18-20, 2011 in the Arena Complex of Šiauliai, Lithuania (Source: Zurkhaneh Review, No.2, July 2011, pp.14-15; Photo-IZSF). The Turks and Turkic world in general share a common Persianate or Turco-Iranian cultural heritage.

Wrestling and weightlifting have remained so popular in Iran, and so closely linked to national pride, that Iranian research universities still produce studies on, for example, the effects of Ramadan fasting on weightlifting performance or the personality traits of weightlifters and martial artists versus players of team sports. Though the nation’s Greco-Roman wrestling team performed the best of any country in this year’s Olympics, Iranian social media users are apparently fuming over one wrestler’s loss to a French opponent, insisting that Olympic referees had conspired against him (no, there’s no evidence).

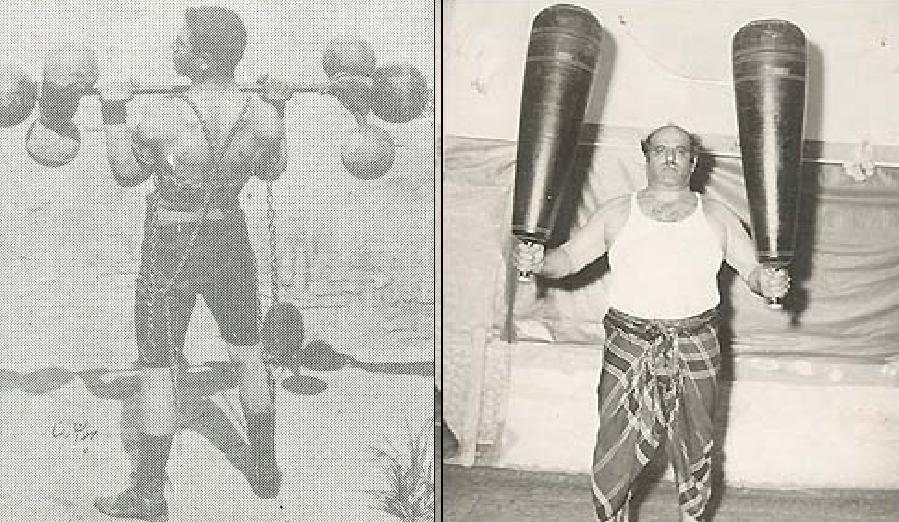

At right is Pahlavan (lit. brave intrepid champion) Mustafa Toosi wielding Zoor-khaneh or Zur-Kāna meels at 60 pounds each (Picture source: Pahlavani.com). Meel training is one of the Zoor-khaneh regimens used for building strength, stamina, and overall physical strength. Each Meel can range from 25-60 pounds and can be as tall as 4 ½ feet. At left is Pahlavan Reza Zanjani with traditional Iranian weights (Picture source: Abbasi, M. (1995), Tarikh e Koshti Iran [History of Wrestling in Iran], Tehran: Entesharate Firdows, page 133).

It’s difficult, and maybe ultimately impossible, to say for sure why one country might do particularly well (or particularly poorly) in one athletic competition or another. And it’s especially difficult to test the theory that Iranians are so good as weightlifting and wrestling (and, to a lesser extent, tae kwon do) because of those sports’ roots in the pre-Islamic Varzesh-e-Bastani tradition, one of the few ancient cultural legacies that has been allowed to persist through the past century of near-endless political turmoil. After all, gold medals in these events are won by a tiny handful of individuals. Still, if even just these dozen or so Iranian athletes believed that their amazing skill was rooted in this particularly Persian heritage, then wouldn’t that in itself make it at least somewhat true?

The Zur-ḵāna welcomed in Africa (Source: Zurkhaneh Review, No.2, July 2011 edition). African Zur-khaneh or Zur-ḵāna athletes have rapidly achieved mastery status in this ancient sport.