The article “Persia – One of the most Fearsome Militaries of the Ancient World” written by Andrew Knighton and originally posted on War History On-line on August 4, 2017. The version printed below has been edited.

Kindly note that excepting one photo, all other images and accompanying captions that appear below do not appear in the original War History On-line posting.

========================================================================================

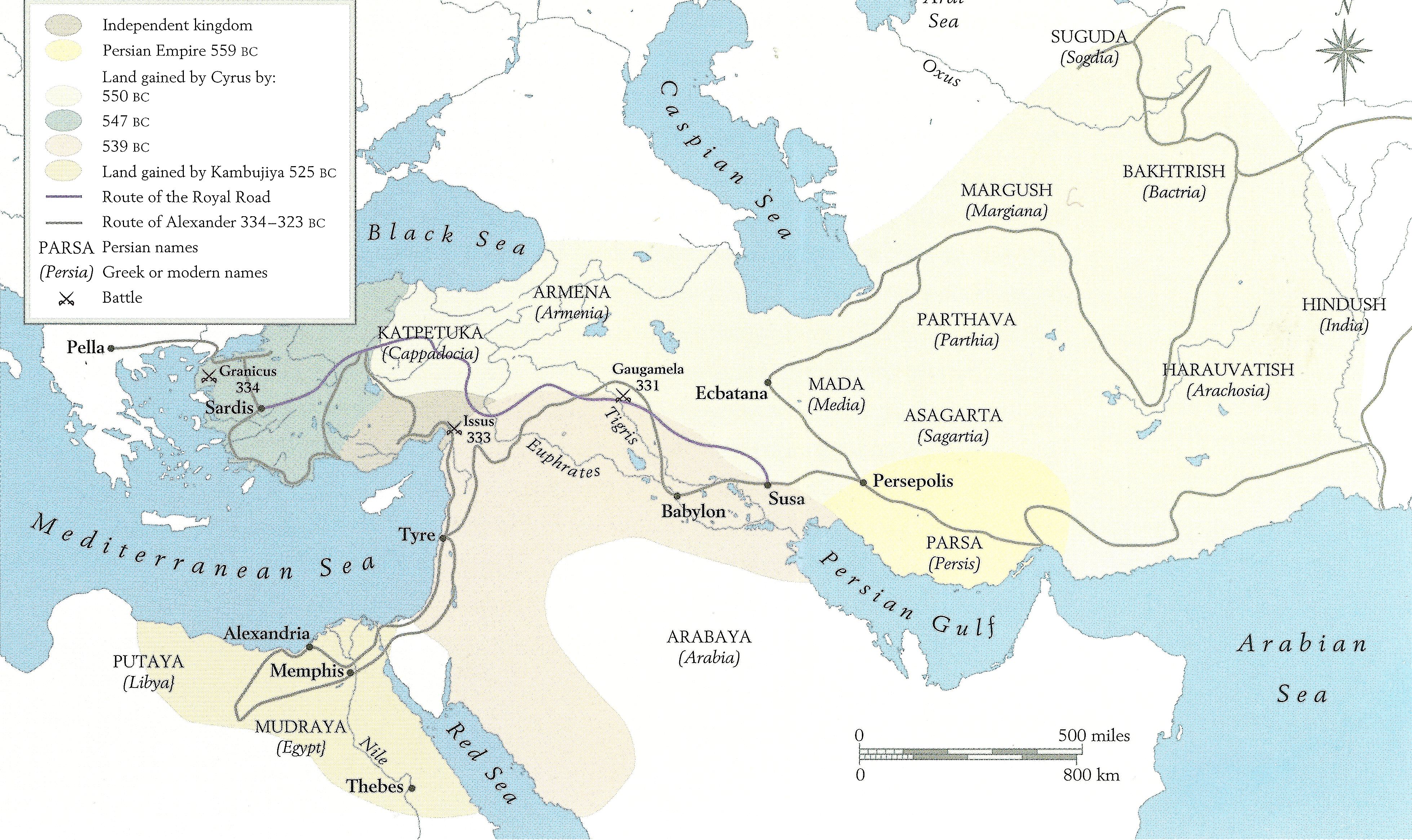

Around 550 BC, the Persians rose to power in the Middle East. Having overthrown the last King of the Medes, Cyrus the Great seized control of territories dominated by the Medes, beginning an empire of his own. A series of campaigns in the west led to the expansion of Persian territory to include Babylon and Lydia.

A map of the Achaemenid Empire drafted by Kaveh Farrokh on page 87 (2007) of the book Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا-:

Here are some facts about the armies with which that empire was forged and defended.

A Military Upbringing

From the age of five until he was 20, every Persian boy was trained in archery and horse riding. After that, he spent four years in compulsory military service. Up to the age of 50, he could be called upon to serve again if needed.

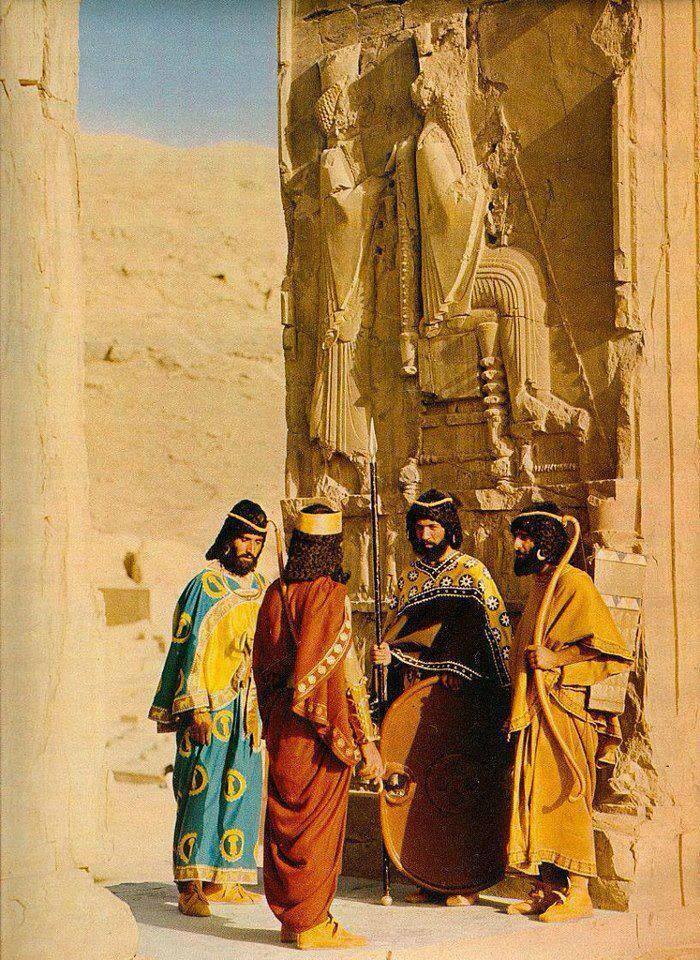

A rare photo from 1971 depicting the reconstruction of Achaemenid troops at Persepolis as they would have appeared during Xerxes’ invasion of Greece in 480 BCE (Source: MedievalJunkie in Deviant Art).

Sparabara

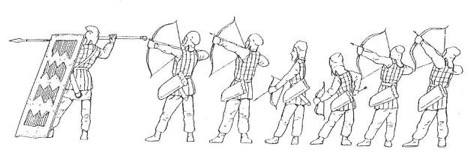

A large part of the Persian Army was made up of archery units. To protect the archers from enemy fire, the units included two sorts of soldiers. Some carried bows. Others instead carried pavises, large shields with which to protect their comrades. These men were the sparabara or “pavise-bearers.”

An Achaemenid Sparabara (Source:Public Domain).

Persian pavises, unlike those of the Middle Ages, were made up of rectangles of leather stretched across a framework and cured to harden them. It made the shields lighter than the solid wooden ones used to protect medieval crossbowmen.

Side view of a row of Sparabara (at front with spear) protecting six rows of archers who are coordinating their volleys (Source: Head, D. (1992). The Achaemenid Persian Army. Stockport, England: Montvert Publications).

The use of sparabara was not a new tactic. The Persians took an approach previously used by the Assyrians and adapted it to their needs. Instead of having an equal number of shield bearers and archers, with a single line of missile troops behind the shield wall, they had more archers than sparabara. It increased the volume of fire a line of shields could support.

Exhibit of Achaemenid archers (Image Source: Ancient Origins).

Persian Units

The Persian Army was divided into regiments a thousand men strong. These were called hazarabam, meaning “a thousand.” The hazarabam was divided into ten sataba of a hundred men, which were further divided into units of ten called dathaba. At each level of this command structure, the unit had its own leader.

Achaemenid Persian officers as they would have appeared during Xerxes’ invasion of Greece.

Divisions of 10,000 were also formed by bringing together ten hazarabam. The Persian name for such units has been lost. The Greeks referred to them as myriads.

Infantry Equipment

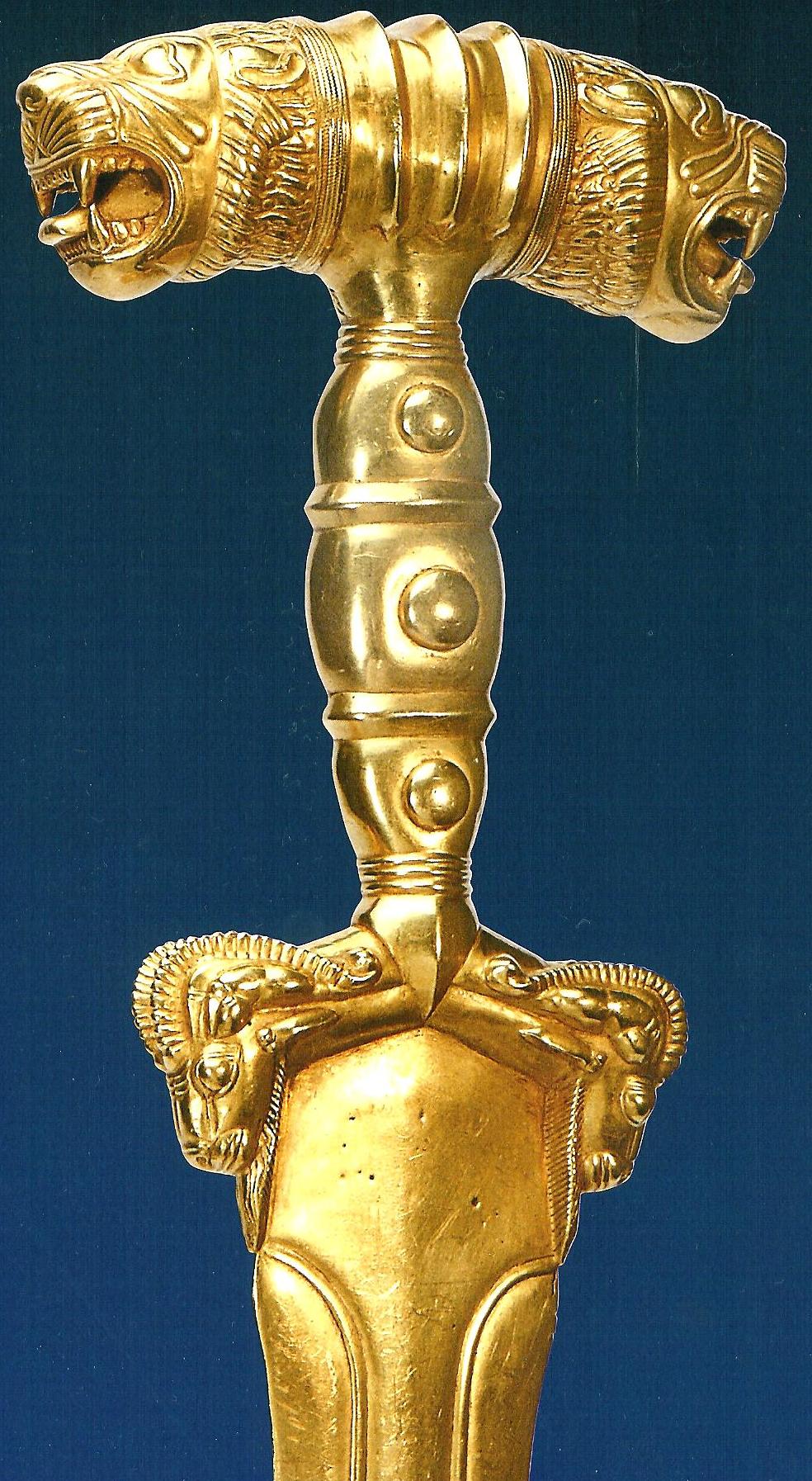

The regular Persian infantry was primarily equipped with bows and falchions; broad swords with a curved blade along one edge. The leader of each dathabam was sometimes armed with a spear so he could defend the others better from his place in the front rank.

Achaemenid Akenakes. Note the lion and ram motifs, both symbols of ancient Iran (Copyright, Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani, Arms & Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period, 2006).

The Immortals

The elite of the Persian Army was a myriad called the Amrtaka, meaning “immortals.” This part of the army was always kept at full strength, drawing from the best available soldiers.

Reconstructions and depictions by Ardashir Radpour of Immortal Guardsmen of the Achaemenid military (Source: Ardashir Radpour & Holly Martin Photography).

At the heart of the Amrtaka were the Arstibara or “shield-bearers,” the elite of the elite. These were all Persians of high social rank, drawn from the rest of the Amrtaka to form the King’s private unit.

Warriors from Conquered Lands

Just like the Imperial Romans and Napoleonic French would do in later eras, the Persians included troops from conquered territories in their armies.

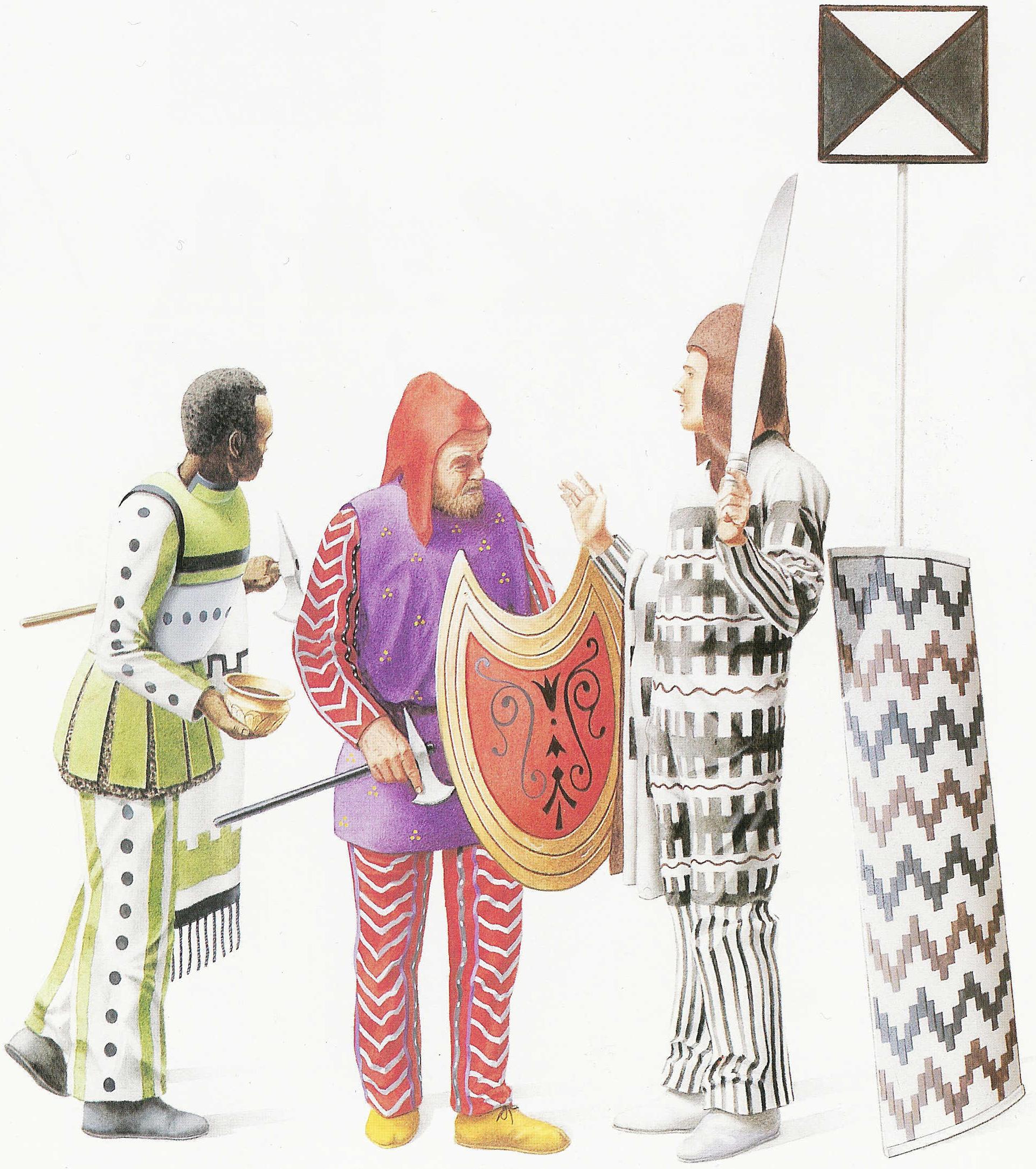

Ethiopian marine (left), Iranian warrior (centre) and Iranian spear bearer (Nick Sekunda, The Persian Army, Osprey Publications, 1992, Plate C; Paintings by Simon Chew).

As the empire expanded, its rulers increasingly turned to mercenaries to fill its army. They provided professional soldiers, took pressure off the Persian population, and made them less reliant on mass levies.

Cavalry

The Persians were initially short of cavalry. To get around this, they used cavalry brought in by conquered nations. The Persians were however supported by their ethnic cousins who supported them with excellent cavalry.

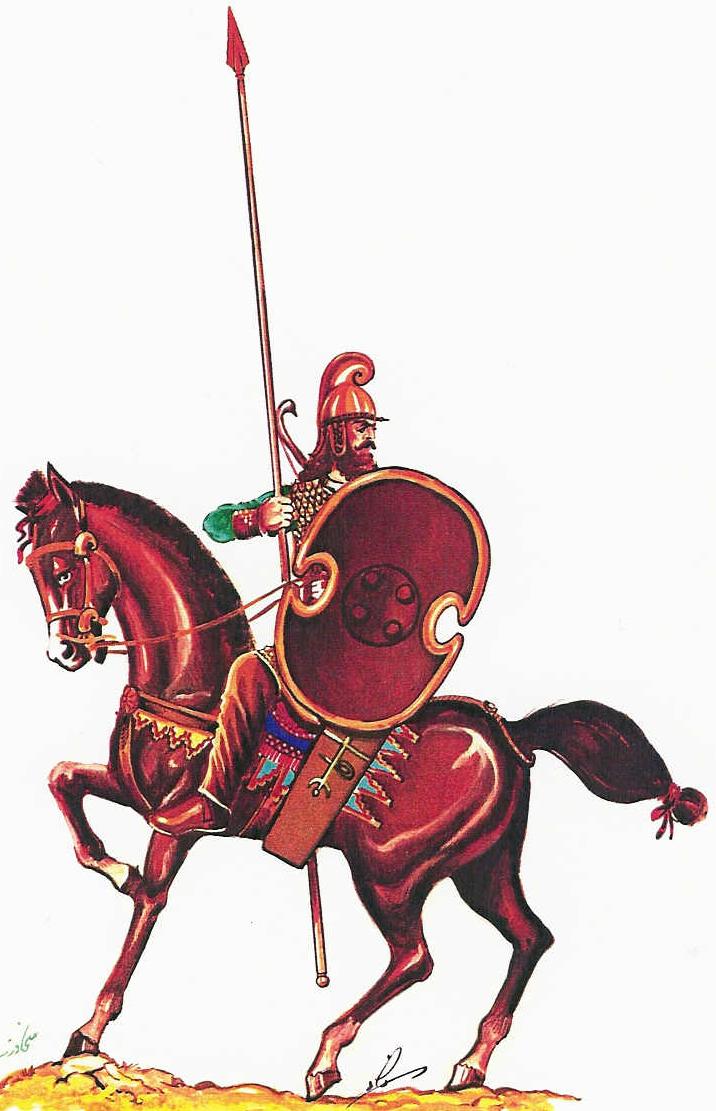

A depiction of a Mede Cavalryman of the later Achaemenid era.

As he expanded the empire, Cyrus the Great became nervous that these allies, especially the Medes, might side with his enemies. To ensure he could not be deprived of cavalry in this way, he created Persian cavalry troops.

To do this, he gave the Persian nobility both horses and the wealth to maintain them, proceeds from his western conquests. He ordered them to ride everywhere and that to travel on foot would be a source of disgrace for a Persian noble.

Having bribed and badgered his nobles into learning to ride, he recruited his cavalry from among them. At its heart was an elite regiment drawn from the Huvaka or “kinsmen,” the 15,000 noblemen at the very top of Persian society.

Persian cavalry, therefore, adopted a clothing style from the Medes, featuring trousers and shorter tunics. These were usually brightly colored, as befitted the noble status of the cavalrymen.

Reconstruction of Achaemenid heavy cavalry in 1971.

Another change took place from the mid-5th century. Persian cavalry began using shields. They were made from wicker and leather to keep them light. These shields were an imitation of those carried by the Saka, which the Persian heavy cavalry regiments adopted.

Founding a Fleet

The early conquests of the Persians were entirely based on land. As they moved west, Egypt came into their sight. To successfully invade Egypt, they needed to be able to support and supply their armies by sea. The Pharaoh Amasis dominated that part of the Mediterranean, so Cyrus the Great’s son and successor, Cambyses, built a fleet.

This fleet not only allowed the Persians to invade Egypt; it also let them launch attacks into Europe.

Reconstruction of Achaemenid ships in 1971.

To crew the expanding fleet, Cambyses recruited men from the coastal cities of Phoenicia. Persian troops still played a vital part in the fleet. They were the marines. Naval combat mostly consisted of boarding actions, so they were responsible for the hard fighting that would win or lose a naval battle.

Takabara

Takabara or “spear-bearers” also became increasingly important in the 5th century. These troops were initially drawn from subject tribes within the empire. Over time, the usefulness of men with spears and shields was increasingly recognized. They became particularly prominent during reforms in the 4th century organized by the Greek mercenary General Iphicrates.

Median (left) and Persian (right) soldiers, carvings at Persepolis. Some scholars speculate that they represent the Immortals (Source: War History On-line).