The article “Cataphract camels” was originally published by the Weapons and Warfare: History and Hardware of Warfare outlet. The version printed below has been edited. Kindly note that two of the images and all accompanying captions do not appear in the original version of the article by Weapons and Warfare.

= = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = = =

The Parthians and early Sassanian Persians also made use of camel units; even experimented with cataphract camels. The early Sassanids have these armoured camels. That may mean they fought, it may only be an experiment to put off Roman javelin Light Cavalry who were deadly to cataphracts whose rear fighting factor was very poor. Contra Armati where cataphracts fight well to the rear, in reality surround them and they are dead meat because the armour blinds them. The Parthian and early Sassanid army was at times additionally supported by camel-borne troops. The animal could bear the weight of the warrior and his armour better and endure harshness longer than the horse; also, the archer could discharge his arrows from an elevated position. These would have made the division very desirable had it not been greatly hampered by Roman caltrop (tribulus) which, scattered on the battlefield, injured the spongy feet of the animal.

A curious creature in appearance, the Cataphract Camel is nevertheless an extremely formidable opponent. They are extremely heavy, and well-armed; in addition, the smell of camel tends to frighten horses. Carrying spears and maces like ordinary horse cataphracts, these units are equally unstoppable against both infantry and cavalry. Their enemies would be wise to treat them with respect.

A Chinese Northern Wei Dynasty (386-534 CE) terracotta sculpture housed at the Musée Cernuschi in Paris, France (Photo: Guillaume Jacquet in Public Domain). This sculpture is depicting a “Western foreigner” camel driver, possibly a Soghdian.

Nations in the Middle East occasionally fielded cataphracts mounted on camels rather than on horses, with obvious benefits for use in arid regions, as well as the fact that the smell of the camels, if up wind, was a guaranteed way of panicking enemy cavalry units that they came into contact with. Balanced against this is the relatively greater vulnerability of camel mounted units to caltrops, due to their having soft padded soles to their feet rather than hooves.

Cataphract camels are well armoured – camel and rider both – shock cavalry. Their primary purpose is to charge into the enemy, using weight and speed to cause additional disruption. The riders carry lances for the initial charge and long maces to continue fighting once in hand-to-hand combat. Recruited from among desert dwelling peoples these soldiers rely on their heavy armour for protection, and their camels are equally well protected. This heavy armour also means that, while they are slow to get moving, they are almost unstoppable in a full charge. They can be used against infantry like any other cataphracts, but their chief virtue is that the smell of the camels upsets horses, giving them an edge when fighting against cavalry.

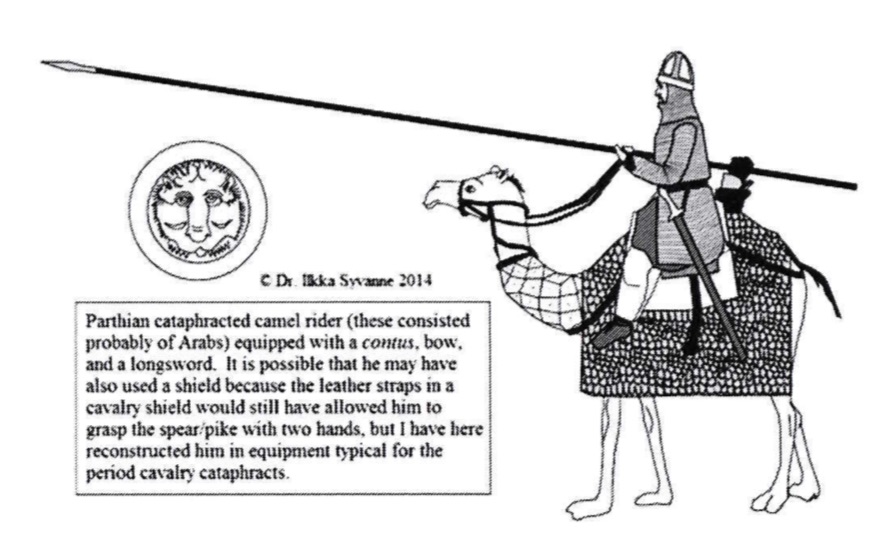

A diagram by Dr. Ilkka Syvanne of a Parthian camel cataphract (Source: Syvanne, I. (2017). Parthian Cataphract vs. the Roman Army 53 BC-AD 224. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, no. 6, pp.33-54).

Our source is a little early history written by the Roman senator Herodian. He wrote a history that starts with the death of Marcus Aurelius, covers the reign of the demented, tyrannical Commodus, his assassination, the subsequent civil wars, the rise and rule of Septimius Severus and the brief and blood-thirsty reigns of his various relatives, culminating in the rise and brutal fall of the demented teenage trans-sexual god-emperor Elagabalus. Something for everyone here, and a brief stage appearance by Parthian cataphract camels can only have added to this unedifying if colorful pageant. Anyway, Herodian IV.14.3 – the battle of Nisibis, AD 217:

“Meanwhile Artabanus was upon them with his vast and powerful army composed of many cavalry and an enormous number of archers and cataphracts who fought on camels, jabbing with long spears.” (Loeb translation)

To reinforce the point, the Loeb translation of Herodian, IV.14.3 has:

Meanwhile Artabanus was upon them with his vast and powerful army composed of many cavalry and an enormous number of archers and armoured riders (kataphraktous), who fought from the backs of camels with long spears, avoiding close combat.

There is no direct evidence for the Parthians using armoured camels. However, Herodian’s use of the word kataphraktous creates a problem. I have argued elsewhere that the word cataphracti and its Greek equivalent denotes heavily armoured men on armoured horses, the type that later became known in the Roman army as clibanarii. If this is correct, Herodian’s use of kataphraktous implies, by analogy, that the camels might be similarly armoured. In a later passage, he speaks of horses and camels in the same terms (Herod. IV.15.2 – again in the Loeb translation):

The barbarians caused heavy casualties with their rain of arrows and with the long spears of the heavily-armed knights (kataphractōn) on horses and camels, as they wounded the Romans with downward thrusts.

Further, it is well known that cataphracti were particularly vulnerable when unhorsed and I have suggested that, consequently, their horses would also have been heavily armoured. Herodian comments that the Parthian horse and camel riders were disadvantaged when on foot (Herod. IV.15.3). It is true that the reasons that he gives are different from that usually advanced, that unhorsed cataphracti were encumbered by the weight and unwieldiness of their armour. Nevertheless, the point remains the same: the Parthian armoured riders should, so far as possible, be protected from becoming dismounted in battle.

A Parthian camel cataphract closing in on the Roman lines with his long lance (Source: Weapons and Warfare).

All this suggests that the contention that the Parthians fielded armoured camels at the battle of Nisibis may not be as far-fetched as might appear at first sight. That said, the experiment (if such it was) seems to have been short-lived. There is nothing after Herodian to indicate the later use of such forces by either the Parthians or the Sassanids.

There is, however, a further complication. A document on papyrus dated January 300, refers to two cataphractarii serving in ala II Herculia Dromedariorum (P. Beatty Panop. 2, 28. See Skeat 1964). It also mentions, however, at least two common soldiers (mouniphikas) in the same ala. Where then do the cataphractarii fit in? It has been suggested that cataphractarius is a rank, replacing the earlier duplicarius and sesquiplicarius (Zuckermann 1994), but it is possible that cataphractarii constituted an elite body within the ala, providing a shock force and adding to its versatility. Another document could support both views (CPR V 13 + P. Rainer Cent. 165. See Rea 1984). It comprises three letters recording stages in the career of one Sarapion. The first, dated 17th April 395, authorises his admission to the schola catafractariorum in an unnamed unit based at Psoftis in Egypt; the second, dated 396, records his promotion to decurio; the third, dated 401, records his discharge on medical grounds. The second of these also mentions the advancement of one Apion from eques to cataphractarius. The same word is used for both Sarapion’s promotion and Apion’s advancement, prov(ectus). In the third letter, Sarapion and others discharged at the same time are placed in three categories: dec(uriones), catafrac(tarii), eq(uites). Nevertheless, the presence in the Notitia Dignitatum of entire units of cataphractarii leads me to favour the second view.

If I am right, what was the model for the cataphractarii in ala II Herculia Dromedariorum? I have argued that normal cataphractarii were well-armoured, though less heavily than clibanarii, and rode unarmoured horses. These men could, therefore, have been equipped in a similar manner but riding unarmoured camels. Alternatively, despite the apparent lack of continuity, they could have been based upon the Parthian camel riders encountered at Nisibis, which would imply that the Parthian camels were also unarmoured. This raises the question of nomenclature – Herodian refers to cataphracti, not cataphractarii – but this is explicable. As I have mentioned elsewhere, the evidence suggests that cataphractarius is a technical term applicable only to troops in the Roman army. If so, it would have been inappropriate for Herodian to have applied it to non-Roman troops. It is also quite possible that the term had not even been coined at the time that he was writing. Either way, he was obliged to use an available expression nearest to what he was seeking to describe, well-armoured cavalrymen, albeit riding camels, and that expression was the Greek equivalent of cataphracti. Of these alternatives, I favour the first.

Where then does that leave the question of whether the camels fielded by the Parthians at Nisibis were armoured or not? The evidence, in my opinion, is equivocal. As is so often the case, certainty is elusive and there is, therefore, room for alternative interpretations.

Bibliography

Rea 1984 – J.R. Rea, ‘A Cavalryman’s Career, A.D.384(?)-401’, ZPE 56 (1984), 79-88

Skeat 1964 – T.C. Skeat (ed.), Papyri from Panopolis in the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, Dublin 1964

Zuckerman 1994 – C. Zuckerman, ‘Le Camp Sosteos et les Catafractarii’, ZPE 100 (1994), 199-202