The article below and its pictures on Georgia in the 19th century Caucasus was originally written and posted in the Poemas del Rio wang Website.

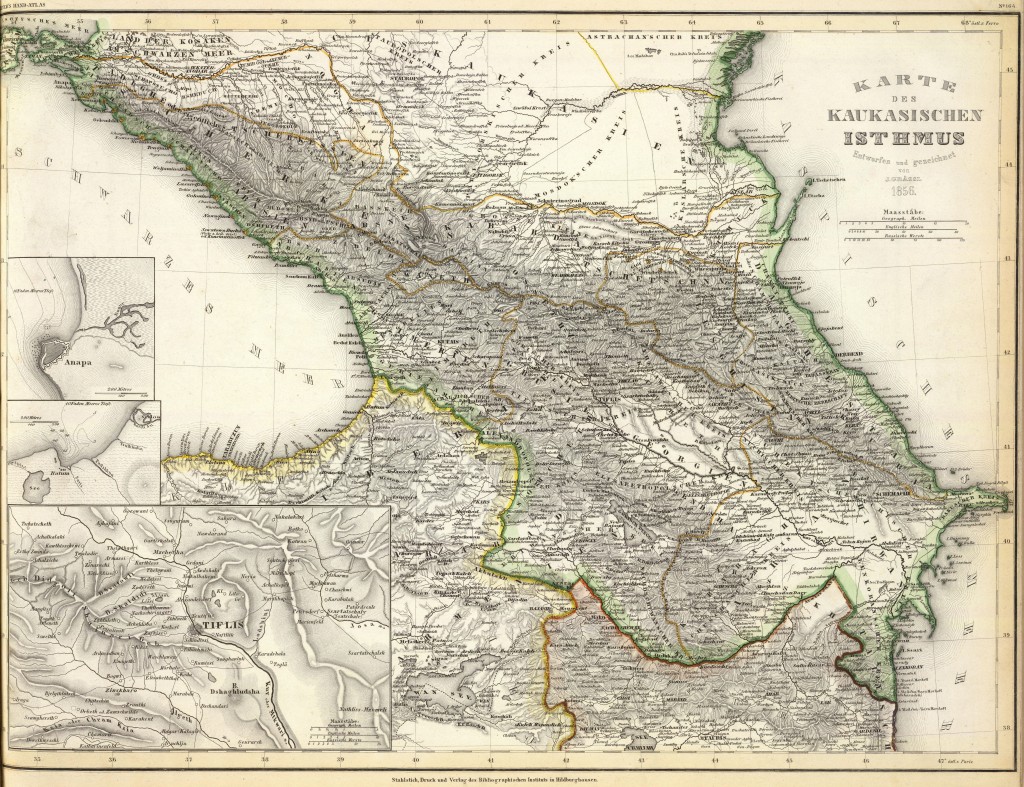

Map of the Caucasus dated to 1856 by cartographer J. Grassl: “Karte des Kaukasischen Isthmus” (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang). Note that the region of the southwest Caucasus above the Araxes River known as “Azerbaijan” since May 1918 was not identified as “Azerbaijan” in historical records or maps. Instead, there are various khnates in the region, identified as Sheki, Lenkoran, Shirwan, etc. The historical Azarbaijan (or Azerbaijan) is located to the south of the Araxes River in northwest Iran.

Map of the Caucasus dated to 1856 by cartographer J. Grassl: “Karte des Kaukasischen Isthmus” (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang). Note that the region of the southwest Caucasus above the Araxes River known as “Azerbaijan” since May 1918 was not identified as “Azerbaijan” in historical records or maps. Instead, there are various khnates in the region, identified as Sheki, Lenkoran, Shirwan, etc. The historical Azarbaijan (or Azerbaijan) is located to the south of the Araxes River in northwest Iran.

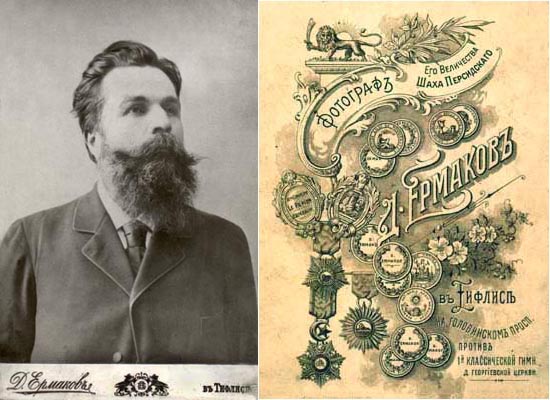

The article below by the Poemas del Rio wang Website pertains to the works of Dmitri Ermakov (1846-1916) in the Caucasus during the 19th century.

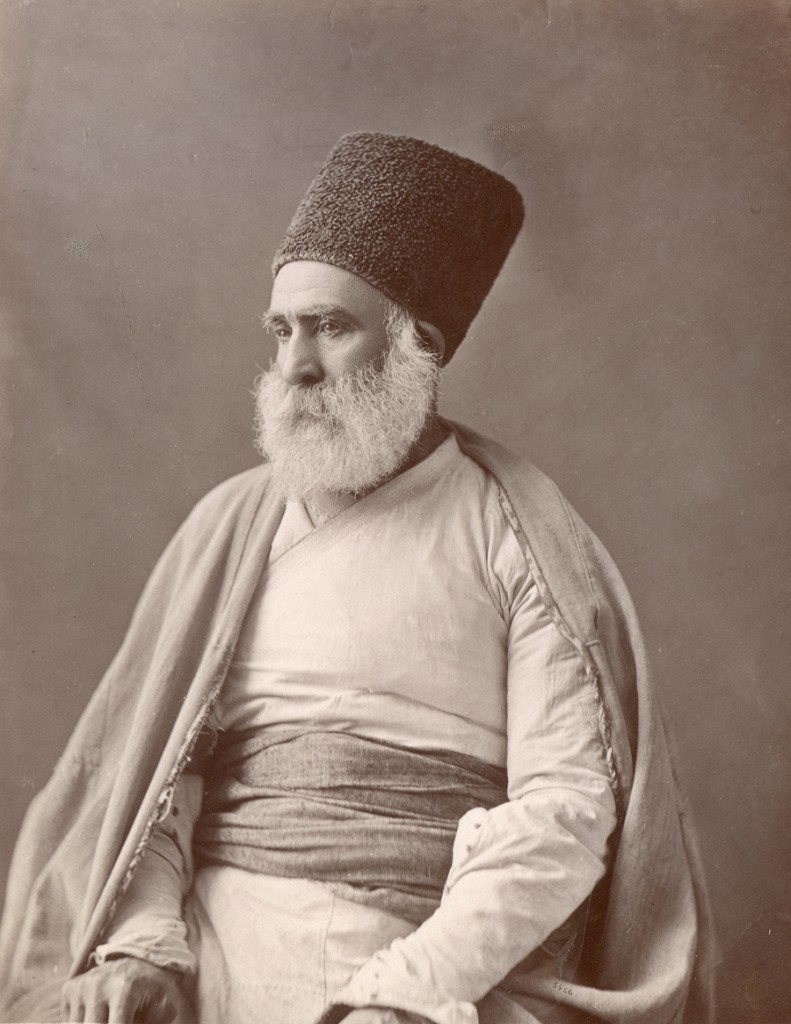

Dmitri Ermakov (1846-1916) (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Dmitri Ermakov (1846-1916) (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

==========================================

This story usually starts being told where some other great stories begin: along the Nile and in the Holy Land, with the photographers who from 1840 onwards provided from here, the most popular East the European audience with albums, and later the participants in the Victorian Grand Tour with post cards representing the local attractions. We will also tell about them later. For now, however, we start the story along the less known Russian thread, with the masters who started taking pictures in the Caucasus and Central Asia, and also reached Persia and Anatolia. Among them, if not the earliest, but one of the most influential photographers was Dmitri Ermakov from Tiflis (1846-1916).

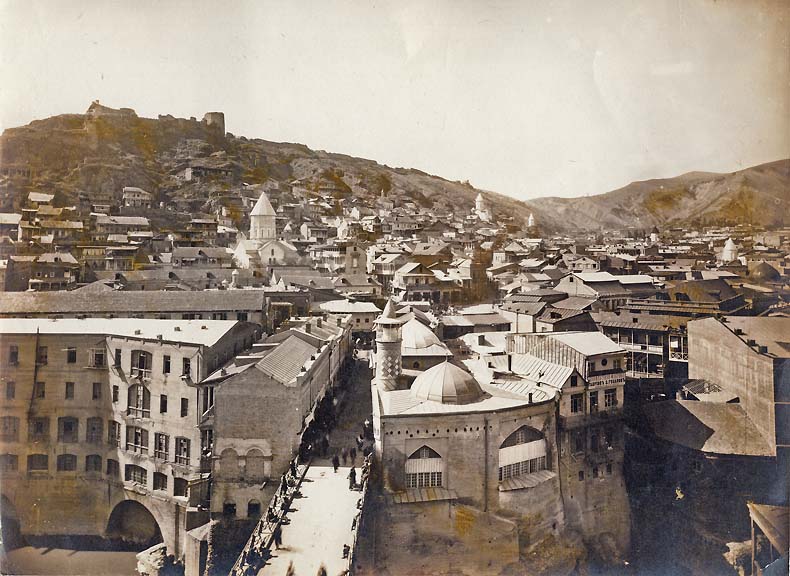

Ermakov’s Tiflis: The market place (Maidan) of the old town with the Shiite mosque and the old bridge over Kura (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Ermakov’s Tiflis: The market place (Maidan) of the old town with the Shiite mosque and the old bridge over Kura (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Tiflis (from 1936 Tbilisi), “the jewel of the Caucasus” which had belonged for centuries to the sphere of Persian culture and came under Russian suzerainty only in 1801, with its mixed Armenian, Azeri, Georgian, Persian, Russian, German, French population – of which we will write more later – was a unique cultural, political and commercial bridge until as far as 1917 between Russia, Western Europe and the Middle East.

Another (closer) view of the market place (Maidan) of the old town with the Shiite mosque and the old bridge over Kura (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Another (closer) view of the market place (Maidan) of the old town with the Shiite mosque and the old bridge over Kura (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

We have mentioned, that the satirical journal Molla Nasreddin which inspired a large number of similar publications from Tehran to Bucharest, was founded by an Iranian Azeri editor-in-chief, illustrated by two local German cartoonists and edited by an international board in Turkish (Azerbaijani) and sometimes even in Russian in Tiflis between 1906 and 1917. The roots of Ermakov were similarly complex. His father, Luigi Cambaggio was an Italian architect, and his mother a well-known pianist from an Austrian-Georgian family who later adopted, together with her son Dmitri, the name of her second, Russian husband.

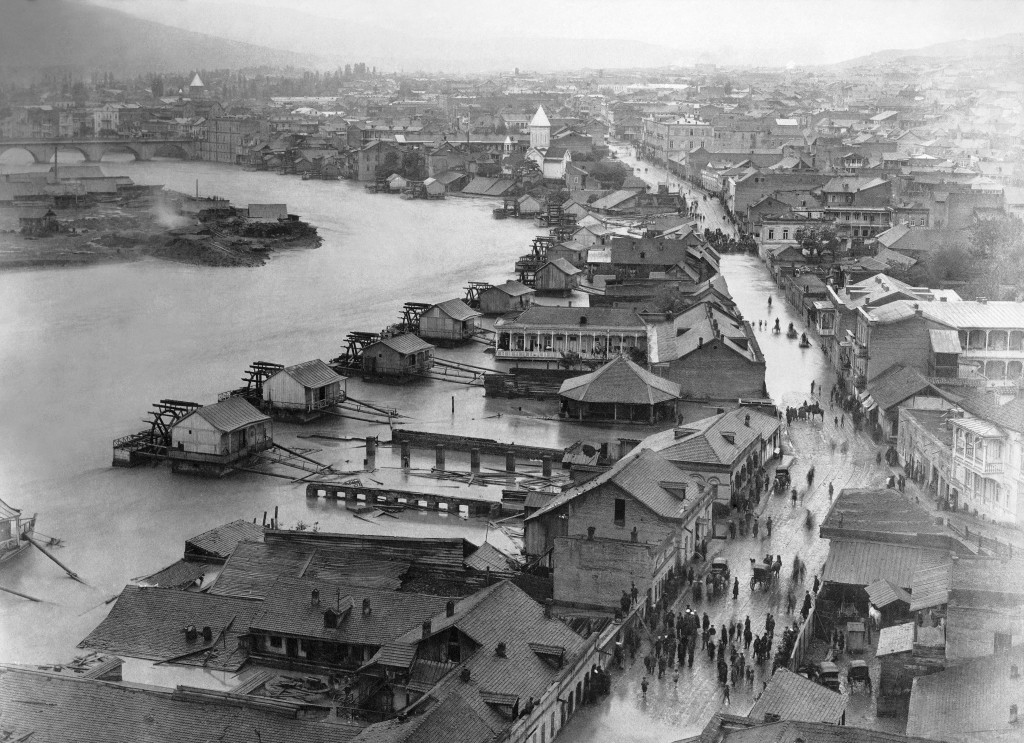

Water mills along the Kura at the time of the flood of 1893 (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Water mills along the Kura at the time of the flood of 1893 (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Ermakov graduated from the military topographic academy in Ananuri, a hundred kilometers north from Tiflis. There he got his first introduction into photography which in the 1860s was already a regular part of the curriculum at military academies. Shortly afterwards, in the early 70s he opened his own photographic studio in Tiflis, on the Dvortsovaya which by this time had become the street of photographers. It was here that in 1846, only seven years after the invention of photography, Henrik Haupt opened the first studio of Georgia, and here worked the “Rembrandt” studio of the greatest contemporary Georgian photographer A. Roinashvili as well. Most probably Ermakov also took over an already working studio, that of Ivanitsky, opened in 1863.

The Dvortsovaya in the 1870s (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

The Dvortsovaya in the 1870s (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Shortly after the opening of the studio Ermakov already became a member of the Société française de photographie, the most prestigious European society of photography. We do not know who nominated him for membership into this society which operated with a strict admission policy. What is certain is that for the 1874 Paris Biennale he already sent 17 pictures, all of them from the Black Sea coast city of Trebizond (Trabzon) in Turkey. By that time he probably also had a studio there, as a lot of photos of him have survived from this region and period.

Zeli-Sultan, son of the Shah of Persia in Austro-Hungarian military uniform (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Zeli-Sultan, son of the Shah of Persia in Austro-Hungarian military uniform (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

By the end of the 70s he was widely considered as a renowned photographer. He won awards in many exhibitions in Moscow, Italy, Turkey and Persia. He regularly took photos in the Persian court and of many Persian aristocratic families, and he was awarded the title of the court photographer of the Shah of Persia.

“In the court gallery of the Shah of Persia there are a large number of paintings representing the Shah himself: in their majority, mediocre works. In these days, however, we had occasion to see a large half-length portrait of the Shah, painted by the Tiflis artist Mr. Kolchin on the basis of the photography by Mr. Ermakov. Whoever previously saw any portrait by Mr. Kolchin, Shishkov, Korganov or Penchinsky, will not be surprised by the brilliant quality of this portrait. Soon, this picture will be delivered to the Court of Tehran where, it seems, this will be the first Russian piece of art.”

– wrote in 1884 the Tiflis newspaper Kavkaz. This news sheds an interesting light on a typical application of late 19th-century photography: that it served as a model for portrait paintings, thus saving long hours of sitting for the model of the portrait. Ermakov even had a common atelier with Pyotr Kolchin for a while in Tiflis, just as one of the greatest Istanbul photographers, Pascal Sébah made model photos for the fashionable Ottoman painter Osman Hamdi Bey.

Georgian officers in Tsikhisdzhiri take a pause during the Russo-Turkish war (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Georgian officers in Tsikhisdzhiri take a pause during the Russo-Turkish war (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Ermakov’s reputation and military training gained him the appointment of the official photographer of the Caucasian front in the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78. As his photos were considered military documentation, they have not been available for more than a century. The National Archives of Georgia published a few of them only in the late 90s. Ermakov’s passion and specialty, however, was ethnographic photography. He made long trips to the most remote valleys of the Caucasus, in Central Asia and Anatolia where he was the first to take photos of the inhabitants of villages of different nationalities.

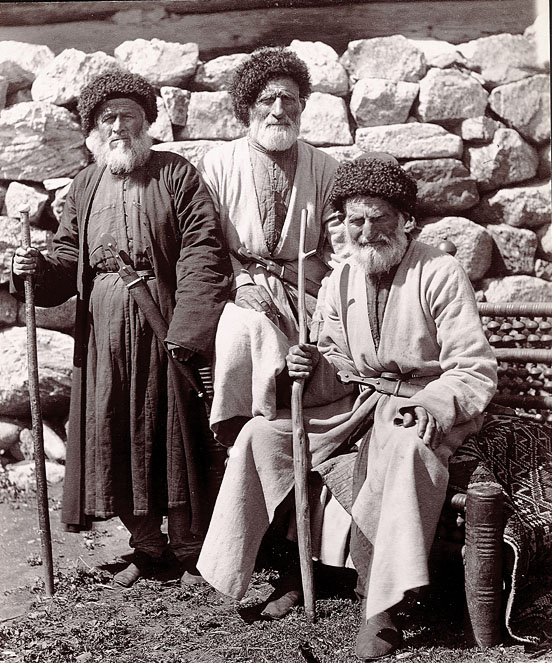

Men from the Georgian mountains (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Men from the Georgian mountains (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Taking into account the needs of contemporary technology, the huge camera, the large – usually 50×60 cm sized – glass negatives preferably used by Ermakov and the mobile dark room, these excursions were veritable expeditions with mule caravans and tent camps, and moreover mostly in mountainous terrain where it was not a simple task to organize a military expedition either.

Women from the Georgian mountains (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Women from the Georgian mountains (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Ethnographic photography was not only a passion, but also a good business investment for Ermakov. For the St. Petersburg and Moscow social circles the Caucasus was since Pushkin and Lermontov the exotic East, the land of unspoiled, noble simplicity and mysterious strangeness, just as Northern Africa was for the contemporary Western European artist. The unimaginable ethnic diversity of the Caucasus was illustrated from the beginning of the century in a large number of engraved and lithographic albums for the educated audience. Over the years, Ermakov published a hundred and ninety two similar albums with his own photos about the ethnic groups, villages and towns, roads and monuments of the Caucasus. In his printed catalog he advertised himself, as early as the turn of the century, with an astonishing photo stock of 25 thousand items.

A photo of the military road in Georgia (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

A photo of the military road in Georgia (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

However, what captures today’s viewer the most in the photos of Ermakov is his attention to the model not as an ethnographic curiosity, but as a person; an attention that suspends the distance in time and culture and creates a relationship between us and the model; a sensitivity which has been the privilege of only a few photographers, then like now.

Fur hat traders in a Tiflis bazaar (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Fur hat traders in a Tiflis bazaar (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

After the death of Ermakov in 1916 his complete huge photographic material was purchased by the University of Tiflis, from where later it got to the Tbilisi State Museum. The following decades were not favorable to their publication. No album, monograph or important exhibition has been made of them, as far as I could investigate. Some of the photos sold by him to the West were eventually exhibited in the 1990s, but I know of no catalog of them. His original albums are a rarity even in the large libraries. We only know some hundreds from his legacy of several thousand photos. Once it will be made public, it will be a huge sensation.

A Turkish man from Georgia (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

A Turkish man from Georgia (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

The son of Ermakov, the first Russian psychoanalyst died in 1941 in prison as a victim of the Stalinist purges. Ermakov’s great-grandson lives today in Moscow. He is a designer and photographer, and a good photographer at that. In his blog he occasionally publishes some scanned photos from the heritage of his great-grandfather. This is one of the most important source of the pictures shown here.

An Iranian man from Georgia (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

An Iranian man from Georgia (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Another important source is the collection of the New York Public Library, more precisely the legacy of George Kennan digitized by them. George Kennan was the first American in the 1870s to travel across the Caucasus, where he purchased lots of pictures from local photographers. They include some from Ermakov as well, sometimes marked with his name by Kennan, while in other cases their provenience is attested only by the characteristic captions printed in small Cyrillic. Most probably a number of other contemporary legacies also include photos purchased from Ermakov.

Princess Lazareva (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

Princess Lazareva (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

A third source is the site of Rolf Gross who in the 1980s lectured in Tbilisi. Having made friends with the director of the museum, he received some test prints of Ermakov’s photos made for local exhibitions and calendars, which otherwise would have finished in the waste-paper basket. Now, after twenty years he published them on the internet. A part of them is known from elsewhere, but about twenty pictures were published by him for the first time.

A Jewish man from the Southern Georgian Akhaltsikhe region (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

A Jewish man from the Southern Georgian Akhaltsikhe region (Source: Poemas del Rio Wang).

We tried to place on the following map of the Caucasus the almost three hundred photos by Ermakov that we managed to collect, but this is an evocative background rather than a precise localization, for most of the available pictures are from Tiflis. And even the scenes represented on the majority of them do not exist any more. The bazaar, the Shiite mosque, the famous bridge of the Maidan, the most beautiful and most characteristic buildings of old Tiflis were all destroyed. Today you can find the atmosphere of Ermakov’s photos only in the Avlabari neighborhood, from where we have not many photos by him. Of old Tiflis, however, we have a large collection of photos both by him and by others. We would like to publish them by linking each to the respective point of a fin-de-siècle map of the city, in this way reconstructing the old Tiflis that has gone.