The article below “A Survey and History of the Persian population of the Caucasus” has been written by Farroukh Jorat. Kindly note that the images and accompanying descriptions do not appear in the original article by Jorat.

=====================================================

Tats (variants of name: Caucasian Persians, Transcaucasian Persians) are the Iranian ethnos, presently living on the territory of Republic of Azerbaijan and the Russian Federation (mainly Southern Dagestan). Variants of self-designation (depending on the region) are Tati, Parsi, Daghli, Lohijon. Tats use Tati language, which together with Persian, Dari and Tajiki relates to the south-western Iranian languages. Azeri Turkic and the Russian language are also spread among Tats. Tats mainly are Shia Moslems, with a little number of Sunni Moslems.

History. Earliest mentioning about the presence of Persians in Transcaucasia relates to the martial expansion of Achaemenids (558-330 BC), during which they annexed Transcaucasia as the X, XI, XVIII and XIX satrapies of their empire

Excavation of the Achaemenid building at Qarajamirli. The researchers Babaev, Gagoshidze, Knauß and Florian in 2007 (An Achaemenid “Palace” at Qarajamirli (Azerbaijan) Preliminary Report on the Excavations in 2006. Ancient Civilizations from Scythia to Siberia, Volume 13, Numbers 1-2,, pp. 31-45(15)) discovered the remains of a monumental building as well as fragments of limestone column bases. This follows closely the plan of an Achaemenid palace featuring a symmetrical ground plan for the building as well as architectural sculpture. The pottery found on the floor closely follow Persian models from theAchaemenid era. Similar structures have been excavated from Sary Tepe (Republic of Azerbaijan) and Gumbati (Georgia). The Sary Tepe, Gumbati and Qarajamirli buildings can be interpreted as residences of Persian officials who left the region when Achaemenid Empire collapsed … for more on this topic see here…

Nevertheless, there haven’t been more information about numerous and permanent Persian population in Transcaucasia since the Achaemenid period. It’s most likely to suppose that ancestors of modern Tats resettled to Transcaucasia in the time of the dynasty of Sassanids (III-VII CE), who built cities and founded military garrisons to strengthen their positions in this region [3].

Shah Khosrau I Anoushirvan (531-579) had presented a title of the regent of Shirvan (the region in the Eastern Transcaucasia) to a close relative of his, who later became a progenitor of the first Shirvanshah dynasty (about 510- 1538) [4].

Panoramic view of the interior of the Atashgah (Zoroastrian fire temple) of Tbilisi (Source: Nader Gohari, 2017).

After the region had been conquered by Arabs (VII-VIII) Islamization of the local population began. Since the XI century tribes of Oghuz, led by Seljuq dynasty started to penetrate into that region. A gradual formation of Azeri Turkic started. Apparently in this period an external name «Tat» or «Tati» was assigned to Transcaucasian dialect of the Persian language. This name came of Turkic term «tat», which designated settled farmers (mainly Persians) [5].

Mongols conquered Transcaucasia in the 30s of the XII century and the state of Ilkhanate was founded. Mongolian domination lasted till 60 – 70s of the XIV century, but that didn’t stop culture from developing – prominent poets and scientists lived and worked there during the XIII – XIV centuries.

In the end of the XIV century Transcaucasia was invaded by the army of Tamerlane. By the end the XIV-XV centuries the state of Shirvanshahs had obtained a considerable power, its diplomatic and economic ties had become stronger. By the middle of the XVI century the state of Shirvanshahs had been eliminated, Transcaucasia had been joined to the Safavidian Iran almost completely.

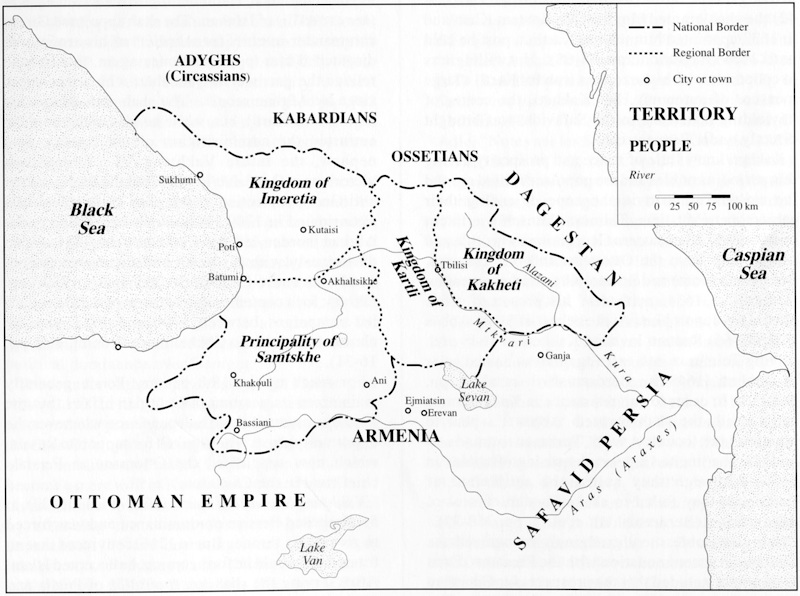

Map of the Caucasus region during the Safavid era (Source: Encyclopedia Iranica).

In the middle of the XVIII century Russia started to widen its influence over Transcaucasia. In the course of the Russian-Persian wars 1803-1828 Transcaucasian region became a part of the Russian Empire.

Since that time we can use data about quantity and settling of Tats, collected by tsarist authorities. When the city of Baku was occupied in the beginning of the XIX century, the whole population of the city (about 8000 of people) were Tats. This is an official result of the first census of the population of Baku, gained by Tsarist authorities.

According to the «Calendar of Caucasus» of the year 1894 there were 124693 of Tats in Transcaucasia [7]. But because of the gradual spreading of Azeri Turkic, Tati was passing out of use. During the Soviet period, after the official term «Azerbaijani» had been introduced into practice in the end of 1930s, the ethnic self-consciousness of Tats changed greatly. Many of them started to call themselves «azerbaijani», if in 1926 about 28443 of tats had been counted [8], in 1989 only 10239 of people recognized themselves as Tats [9].

In the year 2005 American researches, which carried out investigations in several villages of Guba, Devechi, Khizi, Siyazan, Ismailli and Shemakha districts of the Republic of Azerbaijan, indicated 15553 of Tats in these villages.

Summing up we can draw a conclusion, that there is no precise information about the real number of people speaking Tati, but we can presume, that today there are about several thousand of native speakers of Tati living in some villages of Guba, Devechi, Khizi, Siyazan, Ismailli and Shemakha districts of the Republic of Azerbaijan and also in several villages of Southern Dagestan.

Local self-designation of groups of Tati population. Ethnonym «Tati» has Turkic origin; it has been used in Transcaucasia since Middle Ages for naming local Persian-speaking population. Later Persians of Transcaucasia have started to use this ethnonym for naming themselves. The majority of Tati population of Azerbaijan and Southern Dagestan uses the term «tati» or «tat» as a self-designation. Nevertheless today there are some other self-designations of local groups of «Tati» population in Azerbaijan, like- parsi, daghli, lohuj [11].

Parsi. The term «parsi» has been used by tats of Apsheron (Balakhani, Surakhani villages) till the present day as self-designation and also as an indication of tati language «zuhun parsi». This term relates to Middle Persian self-designation of Persians – pārsīk. It is interesting, that the same term also stood for the Middle Persian language itself; compare with – «pārsīk ut pahlavīk» – Persian and Parthian. During the New Iranian language period the final consonant naturally fell off and New Persian form of ethnonym was supposed to become pārsī. But this form wasn’t used in Iran and was replaced by Arabized (and artificial in certain respects) form – fārs.

An Iranian man of the Russian Empire photographed sometime in 1870-1886 (Source: Alex Q. Arbuckle in Mashable Website).

Most likely that Ethnonym «parsi» had been the original self-designation of Transcaucasian Persians, till it was replaced by Turkic name «tat». It is significant to mention that some groups of Persian-speaking population of Afghanistan together with Zoroastrians of India (so-called Parsi) use the term «Parsi» as a self-designation.

(LEFT) Talysh girls from the Republic of Azerbaijan (ancient Arran or Albania) engaged in the Nowruz celebrations of March 21. The Talysh speak an Iranian language akin to those that were spoken throughout Iranian Azarbaijan before the full onset of linguistic Turkification by the 16-17th century CE (RIGHT) Young girls in Baku celebrating the Nowruz.

Lohijon. Citizens of tati settlement Lahij of Ismailli district name themselves after their village «Lohuj» (plural «Lohijon»). Lahij is the most densely populated tati urban village (about 10 thousand citizens). It is situated in the region, which is rather difficult of access; this fact has prevented local population from contacts with outside world and has led to creation of their own isolated self-designation «Lohuj».

Daghli Tats of Khizi district and partly of Devechi and Siyazan districts use another term of Turkic origin – «daghli» («mountaineers») for naming themselves. Obviously, this term has later origin and initially was used by Turki plainsmen of that district for naming tati population living in mountains. In time as a result of spreading of Azeri Turkic, the term «daghli» has strongly come into use and tats of Khizi district started to use it as a self-designation themselves.

At present Tats are making attempts to return to the original self-designation «parsi» together with use of Persian language as a literary standard.

At the 14th of December 1990 during the board of the Ministry of justice of the Azerbaijan SSR the cultural and educational society «Azeri» for studying and development of Tati language, history and ethnography was founded. The primer and the textbook of Tati language together with literary and folklore pieces were published.

Farming Traditional occupations of the Tati population are ploughing agriculture, vegetable-growing, gardening and cattle-breeding. Main cultures are barley, rye, wheat, millet, sunflower, maize, potatoes and peas. Large vineyards and fruit gardens are widespread. Sheep, cows, horses, donkeys, buffalos and rarely camels are kept as domestic cattle.

Blank wall of traditional one- or two-story houses was facing the street. Houses are made of rectangular limestone blocks or river shingles. The roof is flat with an opening for the stone flue pipe of the fireplace. The upper store of the house was used for habitation; household quarters (like kitchen etc.) were situated on the ground floor. One of walls of the living room was provided with several niches for storing of clothes, bed linen and sometimes crockery. Rooms were illuminated by lamps or through the opening in the roof. House furniture consisted of low couches, carpets and mattresses. Fireplaces, braziers and ovens were used for heating.

The closed yard had a garden. There was a verandah (ayvan), a paved drain or a small basin (tendir), covered cattle-pan, stable and hen-house.

Religion Originally Persians, like the majority of other Iranian peoples, were Zoroastrians. After they had been enslaved by Arabian caliphate, Islam became widely spread. Today tats mainly are Shia Moslems, with a little number of Sunni Moslems.

Culture During a long period of time naturalize Persian settlers of Transcaucasia have interacted with surrounding ethnic groups sharing their culture and adopting some elements of other cultures simultaneously. Useful arts like carpet-making, hand-weaving, manufacture of metal fabrics, embossing and incrustation are highly developed. The arts of ornamental design and miniature are also very popular [12].

Spoken folk art of tats is very rich. Genres of national poetry like ruba’is, ghazals, beyts are highly developed. While studying works of Persian medieval poets of Transcaucasia – Khaqani Nezami – some distinctive features peculiar to the Tati language have been revealed.

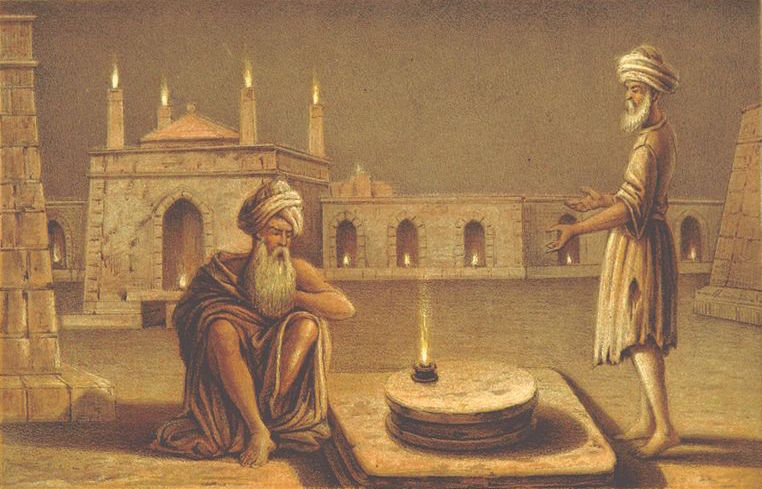

The main fire altar at the Atashgah or Atash-kade (Zoroastrian Fire-Temple) of Baku in the Republic of Azerbaijan (known as Arran and the Khanates until 1918) (Picture Source: Panoramio). This site is now registered with UNESCO as a world heritage site.

As a result of long historical co-existence of tats and Azerbaijani Turkis a lot of common features in the field of farming, housekeeping and culture have developed. Modern Azerbaijani folklore apparently has grown up from Iranian substratum [13].

Traditional women clothes: long shirt, wide trousers worn outside, slim line dress, outer unbuttoned dress, headscarf and morocco stockings, men clothes: Circassian coat, high fur-cap. Great number of Tats live in mountains, work for the industry, social group of intelligentsia has formed.

An elderly Iranian man from the Caucasus as photographed by George Kennan in 1871 (Source: Pinterest).

Tats, Mountain Jews and Armenians

The Tati language was widely spread in Eastern Transcaucasia. It is proved by the fact that down to the XX-th century it had been used by the non-Moslem groups of population: mountain Jews, part of Armenians and Udins [14]. This fact has led to a false idea, that Tats (Moslem), tati-speaking Mountain Jews and tati-speaking Armenians (Christians) are one nation, practicing three different religions.

Tats and Mountain Jews

Mountain Jews belong to the community of Persian-speaking Jews on the basis of the language and some other characteristics. Some groups of this community live in Iran, Afghanistan and Central Asia (Bukharian Jews). Jews of the Central Asia got the name «Mountain» only in the XIX century, when all Caucasian peoples were named «mountain» in official Russian documentation. Mountain Jews call themselves «Yeudi» («Jews») or «Juhuri» [15].

In the year 1888 A. Sh. Anisimov showing the closeness of languages of mountain Jews and Caucasian Persians (Tats) in his work «Caucasian Jews-Mountaineers» came to a conclusion, that mountain Jews were representatives of «Iranian family of Tats», which had adopted Judaism in Iran and later moved to Transcaucasia.

Ideas of Anisimov were supported during the Soviet period: the popularization of the idea of the mountain Jews «tati» origin started in 30-s. By efforts of several mountain Jews, closely connected with regime, the false idea of mountain Jews being non-jews at all, but «Judaismized» tats became widely spread. Some Mountain Jews started to register themselves as tats because of secret pressure from the direction of authorities.

A Daghestani couple photographed in 1910 by Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky (Source: Reorientmag).

As a result of this situation words «tat» and «mountain Jew» became synonyms. The term «tat» was mistakenly used in the research literature as the second or even first naming for Mountain Jews.

This brought to the situation when the whole cultural heritage (literature, theatre, music), created by Mountain Jews during the Soviet period, was arrogated to Tats despite the fact that they had nothing in common with it.

Furthermore, comparing physic-anthropological characteristics of Tats and Mountain Jews together with the information about their languages, we can see that there are no signs of ethnic unity between these two nations.

Grammatical structure of Mountain Jews dialect is much older than the tati language itself. That creates a certain communication gap. [Generally speaking, archaic basis is typical for all «Jewish» languages: for Sephardis language (ladino), which is old-Spanish, for Ashkenazi language (Yiddish) – old-German and etc. At the same time all of these languages are satiated with words of old-Jewish origin.] Having turned to the Persian language, Jews nevertheless kept a layer of adoptions from Aramaic and Old-Jewish languages in their dialect, including those words, which were not connected with Judaic rituals (zoft«resin», nokumi «envy», ghuf «body», keton «linen» etc.) Some word combinations in the language of Mountain Jews have a structure typical for old-Jewish language.

Physic-anthropological types of Caucasian Persians (Tats) and Mountain Jews not only bear no similarities, they are almost opposite to each other.

Two residents of Derbent in the early 20th century (Source: Reorientmag).

In the year 1913 anthropologist K.M. Kurdov carried out measurements of a large group of Tati population of Lahij village and revealed fundamental difference (cephalic index average value is 79,21) of their physic-anthropological type from the type of mountain Jews. Measurements of Tats and Mountain Jews were also made by some other researches. Cephalic index average value for the Tats of The Republic of Azerbaijan differs from 77,13 to 79,21, for Mountain Jews of Daghestan and The Republic of Azerbaijan – form 86,1 до 87,433. Some measurements have also showed that, for Tats mesocephalia and dolichocephalia are typical, while extreme brachycephalia is typical for Mountain Jews, hence there are no facts proving that these two nations are related.

Moreover, dermatoglyphics characteristics (relief of the inside of the palm) of the Tats and Mountain Jews also exclude ethnic similarity.

It is evident, that speakers of Mountain-Jew dialect and Tati language are representatives of two different nations, each owing its own religion, ethnic consciousness, self-designation, way of life, material and mental values.

Tats and Armenians Some sources and publications of XVIII-XX indicate citizens of several Tati-speaking village of Transcaucasia as Armenian Tats, Armeno-Tats, Christian Tats and Gregorian Tats. Authors of these works offered a hypothesis that a part of Persians of Eastern Transcaucasia had adopted Armenian Apostolic Christianity, but they do not take into consideration the fact that those citizens identify themselves as Armenians.

However, the hypothesis that Tati-speaking Armenians are descended from Persians can’t be called reliable and well-founded for several reasons.

An illustration of Baku’s Zoroastrian fire temple (Persian: Atashgah) from John Usher’s 1865 travelogue, A Journey from London to Persepolis (Source: Reorientmag).

Within political situation existing in Transcaucasia in the time of Sassanids and later under Moslem dynasties, Christianity wasn’t a privileged religion. Zoroastrianism dominated in the time of Sassanids, later – Islam. Under such circumstances there were no stimuli for Persian population to reduce their high social status by adopting Christianity.

If Tati-speaking Armenians had been descendant to Persians, they should have used at least some Iranian terms connected with Christian way of life and rituals. But there no such words in their language, which they call themselves «Parseren», i.e. «Persian». All words related to Christianity are exceptionally Armenian: terter «priest» (instead of due Persian kešiš), zam «church» (instead of due Persian kilse), knunk‘ «christening» (instead of due Persian ghosl ta’mid), zatik «Easter» (instead of due Persian fesh),pas «Lent» (instead of due Persian ruze) and etc.

There are evident traces of phonological, lexical, grammatical and calque Armenian substratum in the dialect of Tati-speaking Armenians. Also there are Armenian affricates «ծ», «ց», «ձ» in words of Iranian origin, which do not exist in Tati language. This can only be explained by the influence Armenian substratum.

Regardless the fact that they have lost the language, the group of Armenians managed to preserve their national identity. Important aspect of it is distinct dichotomy «Us-They» with opposition of «Us» («hay») to Moslems («tajik»), Tats and Azeri together with conception of themselves as a suffering part and nation with tragic historical destiny.

Summing up all above-mentioned facts, we can say that «armenian-tats» have always been and now are Armenians, who managed to preserve their Christian religion, but had to accept the Tati language owing to its dominant position and the fact that they were isolated from the centers of Armenian culture.