The prestigious Spanish military journal “Historia de la Guerra” has published an article by Kaveh Farrokh and Javier Sánchez-Gracia on the failed invasion of Iran by Marc Antony in 36 BCE (click the link below in Academia.edu for downloading the entire article):

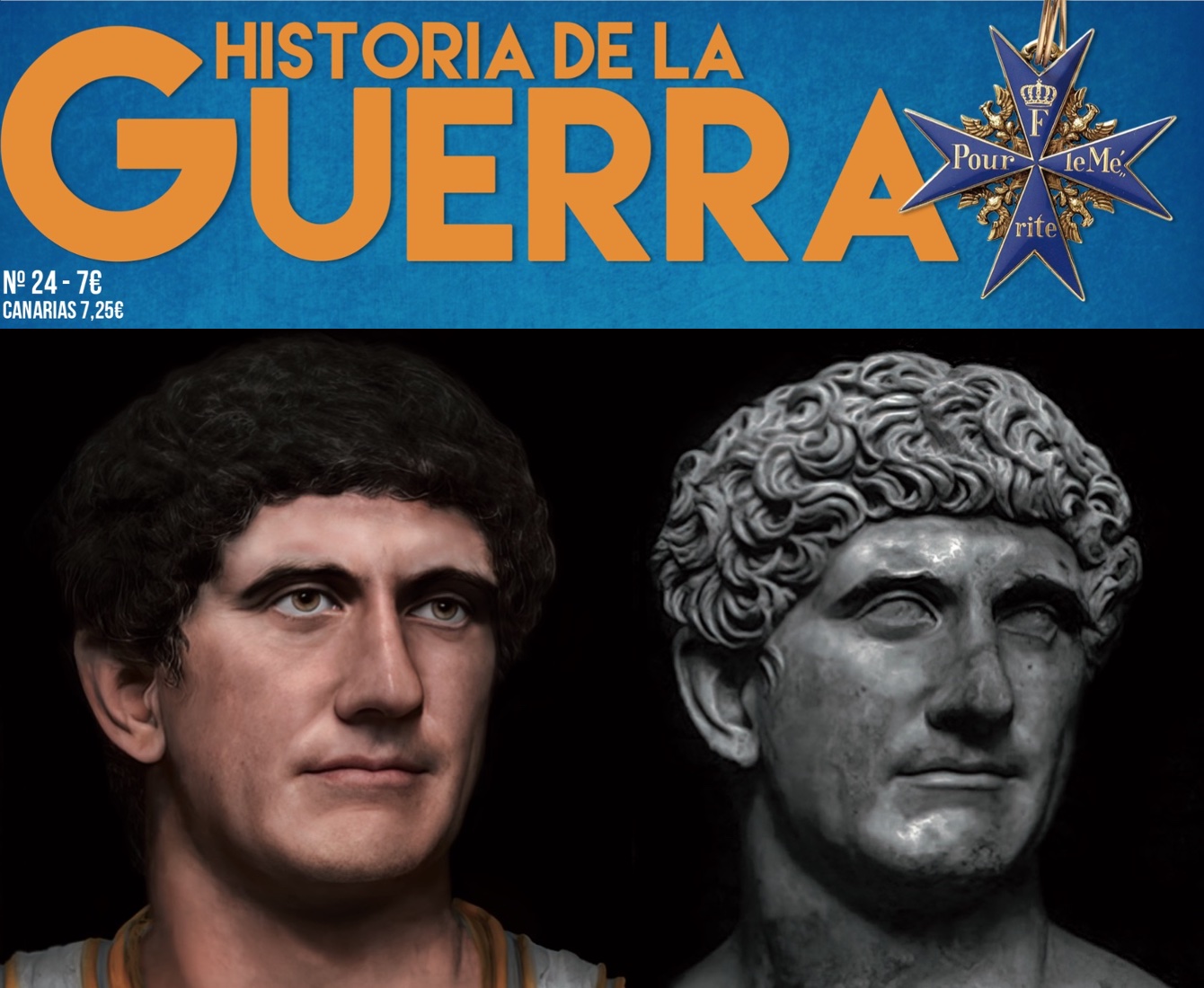

The above illustration at left of Roman statesman and military leader Marc Antony (83-30 BCE) is based on the marble bust [at right] in Rome (Vatican Museums, Chiaramonti Museum). This was published in the 24th edition (summer 2021) of the Spanish military history journal “Historia de la Guerra”.

The above illustration at left of Roman statesman and military leader Marc Antony (83-30 BCE) is based on the marble bust [at right] in Rome (Vatican Museums, Chiaramonti Museum). This was published in the 24th edition (summer 2021) of the Spanish military history journal “Historia de la Guerra”.

Readers further interested in Parthian military history can also download the following articles:

- Sánchez-Gracia, J. & Farrokh, K. (2018/2019). Trajano: los Antoninos Roma y Persia en el Siglo II [Trajan: Antonine Rome and Persia in the 2nd Century]. Zaragoza, Spain: HRM Ediciones.

- Karamian, Gh., & Farrokh, K. (2019). A unique Parthian sword. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, 8, pp.211-214.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Kubic, A., & Oshterinani, M.T. (2017). An Examination of Parthian and Sasanian Military Helmets. In “Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets: Headgear in Iranian history volume I” (K. Maksymiuk & Gh. Karamian, Eds.), Siedlce University & Tehran Azad University, pp.121-163.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Delfan, M., Astaraki, F. (2016). Preliminary reports of the late Parthian or early Sassanian relief at Panj-e Ali, the Parthian relief at Andika and examinations of late Parthian swords and daggers. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, No.5, pp. 31-55.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh. & Kubik, A. (2016). An Examination of Parthian and Sassanian Military Helmets (2nd century BCE – 7th century CE).

Readers further interested in the Parthian Empire and Parthian military history can also consult the following links:

The Farrokh and Sánchez-Gracia article in the Historia de la Guerra journal outlines the military campaign of Marc Antony into northwest Iran (Media Atropatene) in 36 BCE. The military forces of Antony who faced the Parthians and the Medes are examined as well as the tactics of the belligerents. The reasons for the failure of Marc Antony’s campaign in Iran are also analyzed in the article.

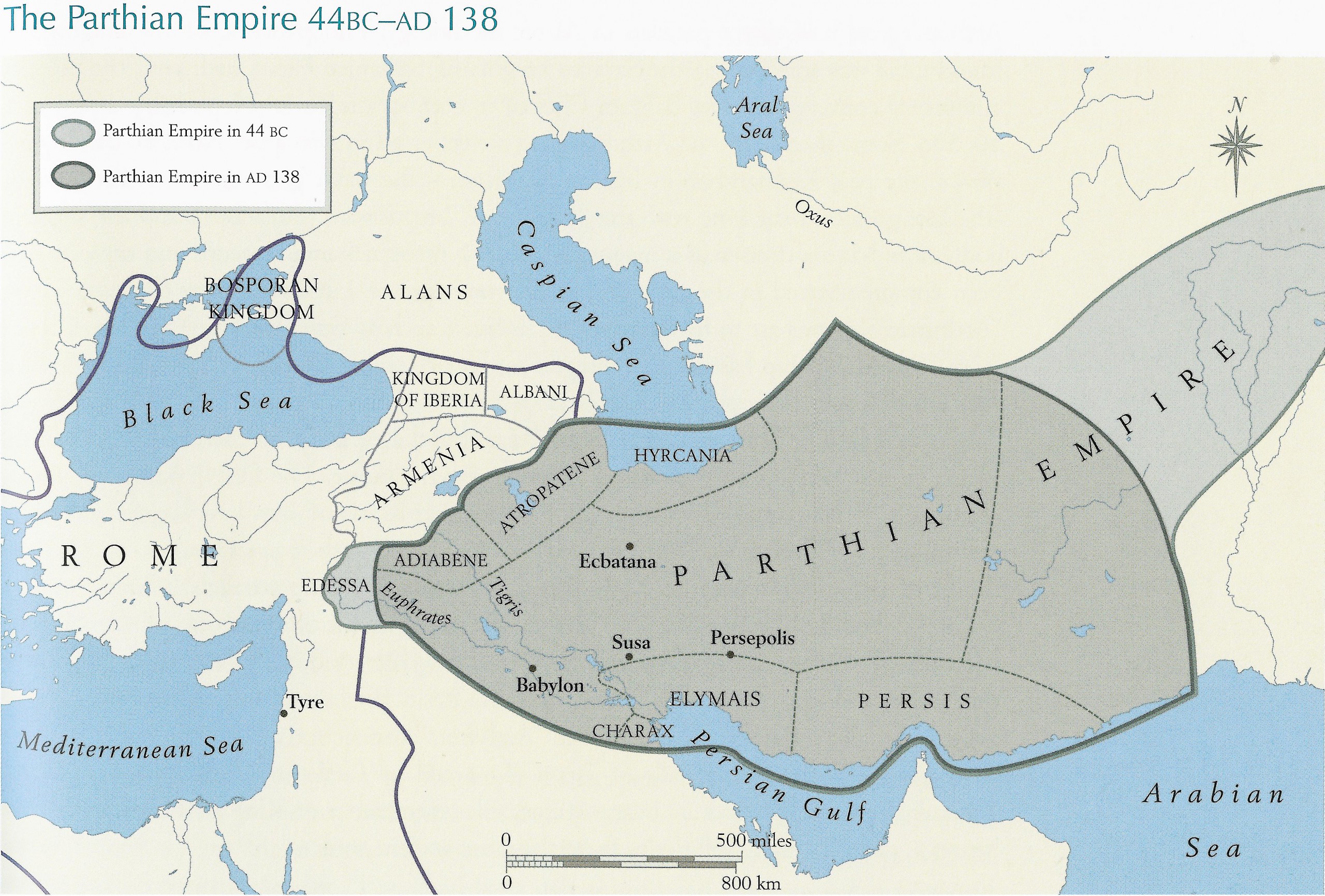

Map of the Parthian Empire in 44 BCE to 138 CE (Picture source: Farrokh, page 155, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

Marc Antony’s invasion force outnumbered the Parthians by a margin of two to one. This invasion force (a maximum estimated size of 100,000 troops) was to be one of the largest Roman armies to attempt the conquest of Iran.

Detailed Reconstruction of a Roman Centurion by Luc Viatour at Boulogne (Source: Luc Viatour – https://Lucnix.be). Roman centurions such as these (and all Roman soldiery in general) were the foremost in close quarters combat during the classical era. These proved instrumental in carving out for Rome a massive and powerful empire encompassing much of Europa, Africa and the Mediterranean regions. Despite their prowess, ingenuity and bravery, the Romans were unable to conquer the Parthians and later Sassanians of ancient Iran.

Prior to Marc Antony, Julius Caesar had been planning an invasion of the Parthian empire, but his campaign never took place as a result of his assassination in 44 BCE.

Parthian cavalry and banners (Picture source: Farrokh, page 130, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا– these drawings originally appeared by Zoka in the 2,500 Year Celebrations of the Persian Empire in 1971).

Phraates IV was the king of the Parthian empire when Antony invaded Iran. Marc Antony had vastly underestimated the martial capabilities of not just the king but the Parthians and Medes in general.

Drachm Coin of Phraates IV minted at Mithradatkert (Public Domain & Classical Numismatic Group).

Antony’s siege of the city of Praaspa in Media Atropatene (in modern northwest Iran, the historical Azarbaijan region) also faltered, especially when the Medes launched a ferocious assault against the Romans, forcing these to flee. Antony was so enraged that his troops had actually fled, that he ordered them to be subjected to the punishment of decimation (the execution of one soldier of every unit of ten men).

An illustration of Marc Antony’s army laying siege to Praaspa (believed to have been located near modern-day Tabriz) (Picture source: Copyright of HRM, Spain). In practice many of Antony’s siege engines had already been destroyed by a devastating Iranian cavalry attack before these could arrive to Praaspa.

In one of the engagements, the Parthians and their Mede allies destroyed 10,000 Roman legionnaires and virtually the major portion (if not all) of Antony’s siege engines (meant for the capture of Praaspa). The Roman commander Statianus was also killed during that battle.

A stucco discovered at the Zahak site, now housed in the Museum of Azarbaijan in Iran. The image depicts a Mede infantryman of the Parthian era. It was Mede infantry such as these who helped defeat the invading troops of Roman general Marc Antony in 37 BCE (Photo sources: Images forwarded to Kavehfarrokh.com by Tara Farhid-Gallo in the article –گردایه (مجموعه) باستانی آژدهاک ( ضحاک ) آذرآبادگان– and in Darvakeran Blogspot).

Antony’s massive army had also included large numbers of non-Roman auxiliaries such as 10,000 Iberian and Celtic cavalry plus another 30,000 (non-Roman) cavalry and infantry forces.

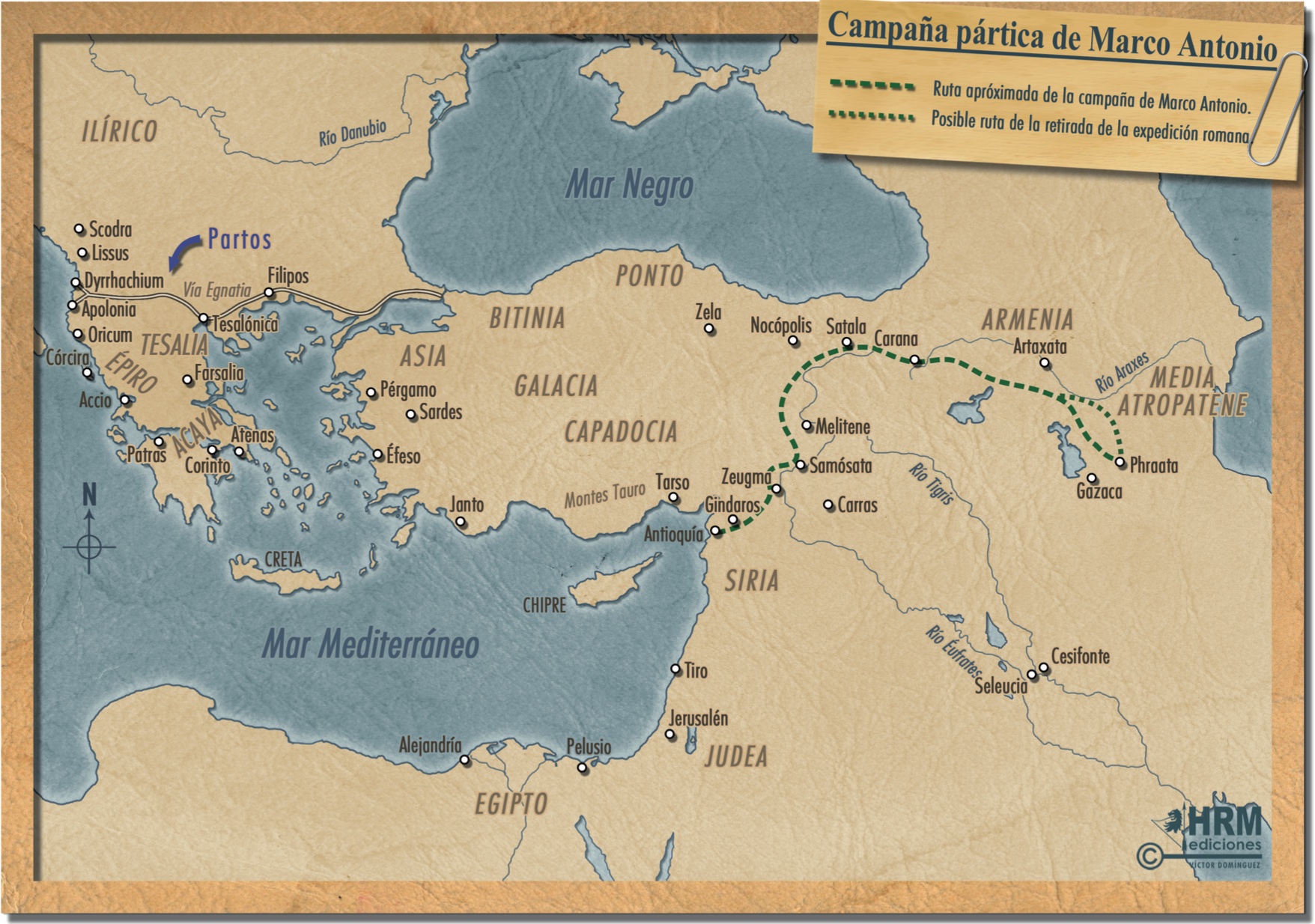

Map of Marc Antony’s invasion of northwest Iran through Armenia and the subsequent withdrawal of the Roman forces in 37 BCE (Source: Copyright of HRM, Spain).

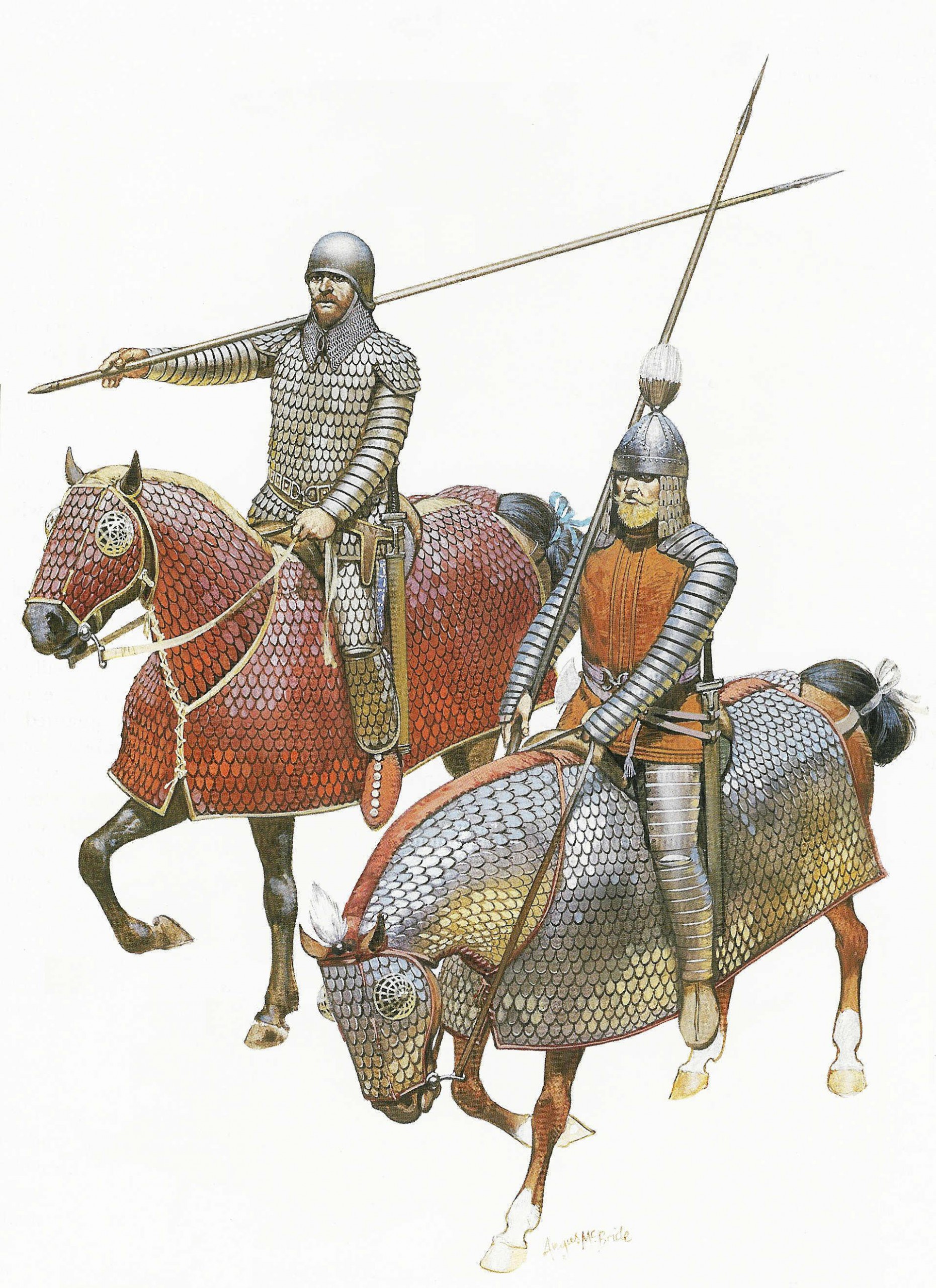

Marc Antony’s expedition into Iran ended in disaster in 36 BCE mainly at the hands of Parthian and Mede armored knights and horse-archers.

Reconstruction by Peter Wilcox and (the late) Angus McBride of the Parthian Asbaran (armored lancer knights) as they would have appeared in the 1st century BCE (Source: Osprey Publishing, Men at Arms Series 175, Plate A).

Antony and the remnants of his defeated army managed to escape to Armenia. Roman losses are estimated at between a quarter to a third of Antony’s original force of 100,000-men. The Romans were to lose another 8,000 troops to weather conditions during Antony’s march into Syria from Armenia. Antony and his surviving troops then marched to Egypt where Ptolemid Queen Cleopatra provided them with sanctuary (For more details consult Farrokh, 2007, p.144-146).

Parthian Shiva-tir (Horse Archers) engaged in discharging their missiles (Source: Ancientbattles.com).

The Parthian king Phraates IV officiated his triumph over the Romans by striking over their captured coins – these were originally portraying Antony and Cleopatra.

Armenian king Artavasdes II (r. 55-34 BCE) (Source: Copyright of HRM, Spain). He had promised to support Antony with his powerful cavalry and infantry forces but decided to abandon the Romans during the campaign in 36 BCE. Antony was to take his revenge on the Armenian king after the campaign by having him arrested and bound in chains. It is also possible that another reason for the arrest of Artavasdes were suspicions that he had been in communication with Antony’s rival Octavian. Enraged at the arrest of their king, the Armenians (especially their men-at-arms) led by Artaxias II (son of Artavasdes) rebelled against the Romans but were put down with brute force. Artaxias II managed to escape capture by the Romans to find refuge among the Parthians in Iran.

Antony’s only success in his otherwise disastrous campaign was that he had managed to rescue the remainder of his army from destruction.