The article “Parthian Warfare” written by Patrick Scott Smith was published on the Ancient History Encyclopedia on September 4, 2019. The version printed below has been edited in kavehfarrokh.com.

Kindly note that the images and accompanying captions printed below do not appear in the original Ancient History Encyclopedia publication.

Readers are also referred to the following Resources for download from Academia.edu:

- Karamian, Gh., & Farrokh, K. (2019). A unique Parthian sword. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, 8, pp.211-214.

- Sánchez-Gracia, J., & Farrokh, K. (2018/2019). Trajano Pártico: Las victoriosas campañas de Trajano en Persia, 114-117 d.C. [Trajan Parthicus: The victorious campaigns of Trajan in Persia, 114-117 CE]. Zaragoza, Spain: HRM Ediciones.

- Karamian, Gh., Farrokh, K., Kiapi, M.F., Nemati, H. (2018). Graves, crypts and Parthian weapons excavated from the gravesites of Vestemin. HISTORIA I SWIAT, No.7, pp. 35-70.

- Farrokh, K. (2018). Parthian era Amazons? Placing the Weapons finds at Vestemin in Historical Context. The Eleventh Annual ASMEA (Association for the Study of the Middle East and Africa) Conference November 1-3, 2018, Washington DC.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Kubic, A., & Oshterinani, M.T. (2017). An Examination of Parthian and Sasanian Military Helmets. In “Crowns, hats, turbans and helmets: Headgear in Iranian history volume I” (K. Maksymiuk & Gh. Karamian, Eds.), Siedlce University & Tehran Azad University, pp.121-163.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh., Delfan, M., Astaraki, F. (2016). Preliminary reports of the late Parthian or early Sassanian relief at Panj-e Ali, the Parthian relief at Andika and examinations of late Parthian swords and daggers. HISTORIA I ŚWIAT, No.5, pp. 31-55.

- Farrokh, K., Karamian, Gh. & Kubik, A. (2016). An Examination of Parthian and Sassanian Military Helmets (2nd century BCE – 7th century CE).

For more information on Parthian military history consult:

Military History and Armies of the Parthians

========================================================================

Parthian warfare was characterized by the extensive use of cavalry and archers. Coming at enemy troops from all directions Parthian riders created confusion and wreaked havoc. They even developed the famous “Parthian shot.” Able to shoot backward at full gallop, the Parthian archer delivered kill shots at pursuing cavalry. Just as essential were their heavy-armored horse cavalry called cataphracts that provided offensive support and assistance in mopping up remaining pockets of resistance with long lances and swords. Taking over the Seleucid Empire, Parthia (247 BCE – 224 CE) controlled territories that stretched from the Mediterranean in the west to India and China in the east and were even a match for the Romans. About Parthia’s ability to wage war, Strabo mentions:

“… they were well adapted for establishing dominion, and for ensuring success in war” (11.9.2).

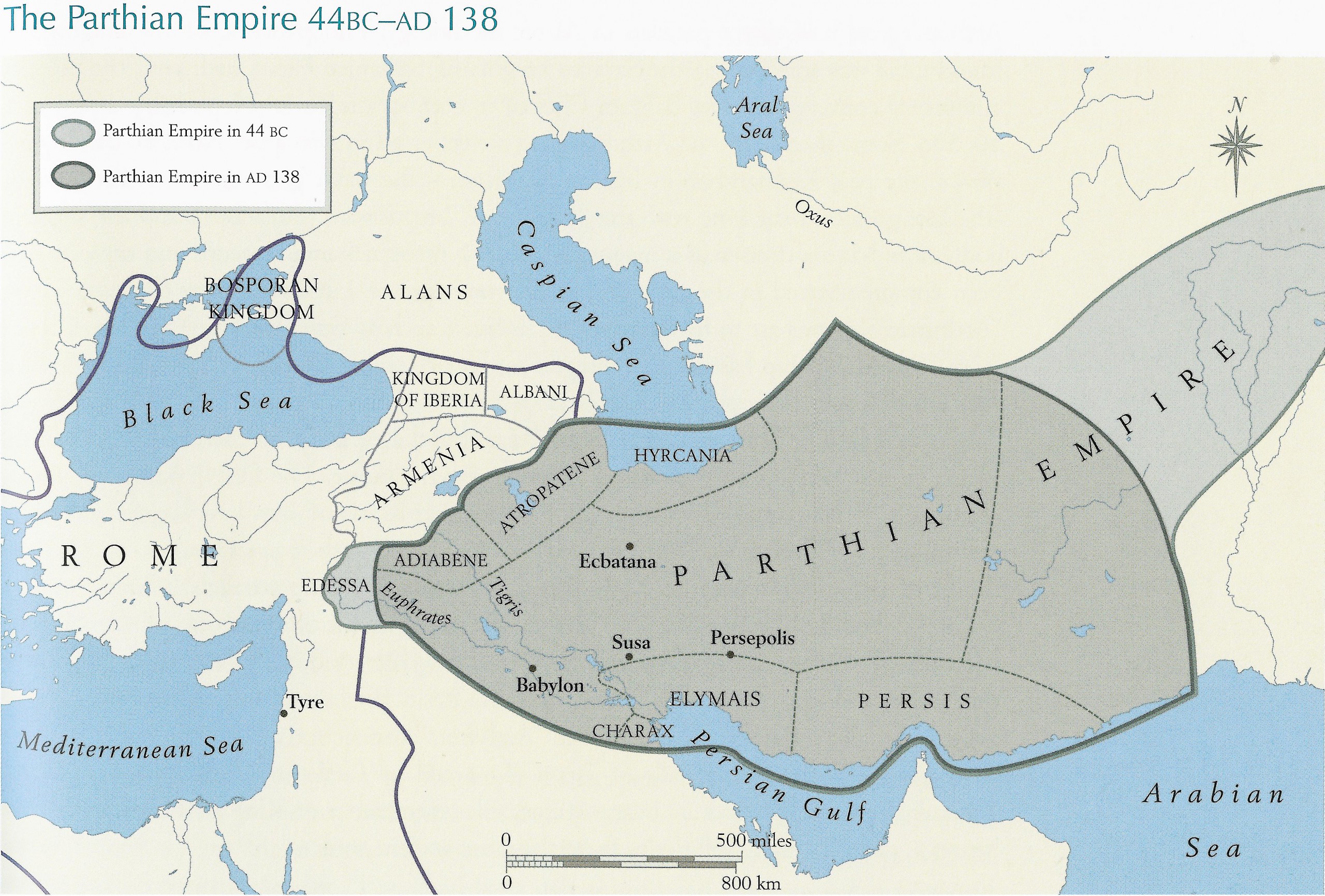

Map of the Parthian Empire in 44 BCE to 138 CE (Picture source: Farrokh, page 155, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

Parthian Cavalry

Coming off the flat steppe region of central Asia, more than one ancient author mentions Parthian cavalry as essential to their military machine. Consummate in their military tactics and organization the Parthians were also excellent horse breeders and trainers. Strabo says that their horses were superior in “fleetness” (3.4.15). That they were the fastest around meant their riders could chase down the enemy when in pursuit, or escape when pursued. It is likely, as well, like many warhorses of old, Parthian horses were trained to trample enemy infantry or unhorsed cavalry. But the value of a horse’s ability to turn on a dime was appreciated early on. Writing in the late 5th and early 4th centuries BCE, Xenophon mentions, in his Art of Horsemanship:

“Another point which is necessary to learn is, whether when let go at full speed the horse can be pulled up sharp and is willing to wheel around in obedience to the reins.” (section 3)

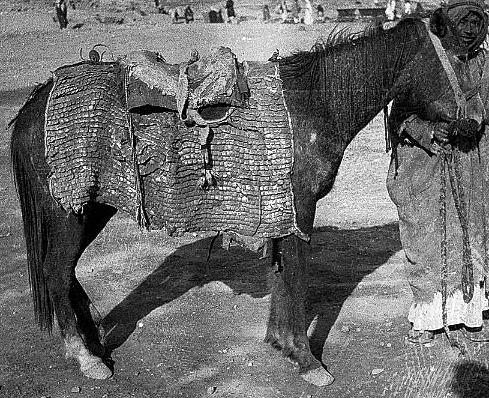

Horse armor (Bargostvan) constructed of metal scales discovered at Dura Europus mounted on leather for a horse (Picture source: Stlcc.edu).

Maneuvering like today’s barrel race riders, the importance of the mounted warrior to whirl about their horse during military engagement – to attack the flank of pursuing cavalry, to change direction to help fellow warriors, or to have the advantage of maneuverability during one-on-one combat with enemy cavalry – would have been fundamental for Parthian mounted troops. Strabo also mentions the other part to the Parthian horse’s superiority was “their ease in speedy traveling” (3.4.15). This not only would have helped the aim of the mounted archer delivering kill shots at full gallop but just as important, it meant the rider would not be worn out from riding a choppy gaited horse.

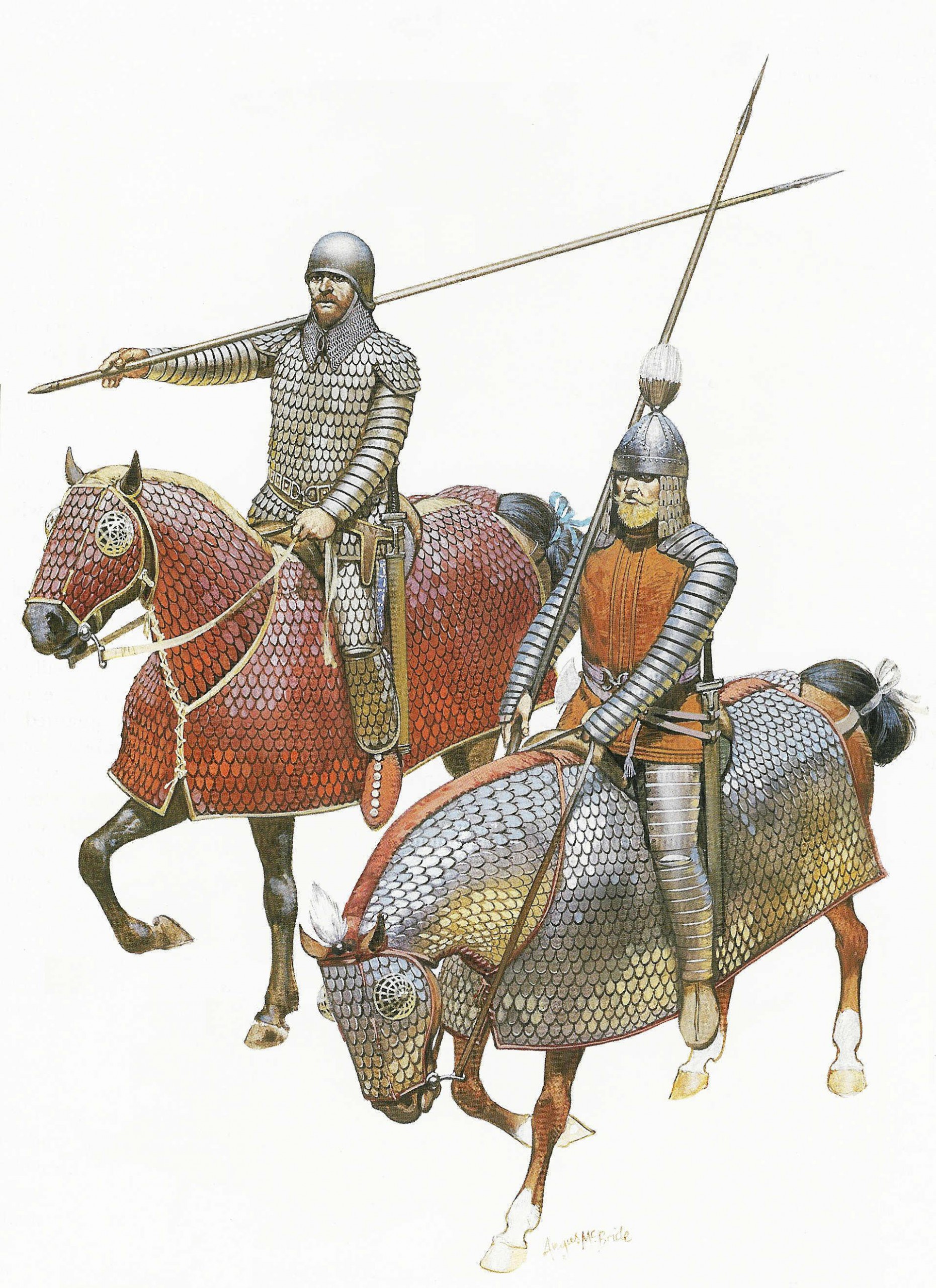

Parthian cavalry and banners (Picture source: Farrokh, page 130, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا– these drawings originally appeared by Zoka in the 2,500 Year Celebrations of the Persian Empire in 1971).

At times Parthian cavalry would have ranged some distances to get to a field of combat. Getting there quick would have been crucial, but getting there on the backs of smoother riding horses meant less fatigued warriors able to freshly engage at a moment’s notice. That the Parthian horses were superior to others and key to Parthia’s military superiority for such a long time, reveals ownership of a highly organized, closely-held horse industry that produced superior animals while using state of the art training methods.

Armor and Weapons

Once on their horses, no matter how skilled their riders or horses were, they still were the target of lethal projectiles. Protection of warrior and horse would have been crucial. Parthia’s cavalry was divided into two parts: light and heavy. The light cavalry consisted of archers on horseback. Dressed in tunic, trousers, and sometimes fabric headgear (pointed and possibly padded) their protection was from the speed and maneuverability of their horses and the fact they shot from a distance.

The weaponry of the horse archers was primarily the composite bow and a quiver of arrows. Their bows were a laminate of wood, sinew, and horn. They were recurved in shape to accelerate the arrow’s release, thus gaining greater impact, distance, and accuracy. Early on, the shafts of their arrows may have been tipped, in the Scythian fashion, with bone arrowheads. According to Plutarch, at the Battle of Carrhae (53 BCE) the Parthians were using arrows with barbed tips, shot with a “velocity and force that fractured armor, and tore their way through every covering alike, whether hard or soft” (Crassus, 24.4). This is indicative of heavier metal-tipped arrows released from bows that were so strong the arrow’s impact was not diminished. Plutarch confirms their bows were “large and mighty, so as to discharge their missiles with great force” (24.5). While their primary purpose was not to engage the enemy directly, the Parthian archer’s cache of weaponry also included a short sword, up to one meter (about three feet) in length.

Royal family members at Hatra attired in Parthian dress (Picture source: Farrokh, page 150, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

The Parthian heavy cavalry, called cataphracts, on the other hand, consisted of a fully armored rider and horse. Protection for the rider would include mail or scale armor that covered the whole body: neck, torso, legs, and a metal helmet for the head. For the horse: scale armor would have also provided thorough protection for the animal’s body. Weaponry for the cataphract rider would have included a long metal-tipped lance and long sword.

Military Strategy and Tactics

While little is known about Parthia’s line of command, it is obvious their success at war required a hierarchical structure of lieutenants answerable to a supreme commander who answered to the king. Dependent on their horse archers and cataphracts, Parthia’s strategy was to fight the enemy on terrain that favored their cavalry. Their objective was to keep their causalities to a minimum by avoiding direct combat with the enemy. With a hit-and-run fighting style, Parthia’s tactics were well suited to counter the concentrated troop movements of others. With archers on the fleetest of horses, and camel riders providing a steady supply of arrows, they made sitting ducks of infantry unable to engage except at close range. Though infantry was a minor part of their military apparatus, when circumstances called for it, troops from allied vassal states were recruited and employed.

Parthian armored lancer (Picture Source: Civilization Fanatics Center).

One tactic was to wear down, frustrate, and if possible separate enemy troops from their supplies or each other. This was accomplished with feigned retreats that drew the enemy out to finally meet a lethal volley of arrows. While their cavalry was divided into light horse and heavy cataphracts, the two contingents worked in concert. Whereas the light horses were reasonably inexpensive to outfit and were rode by recruits of commoner origin, the cataphracts with all their armor and accouterments were extremely expensive. Their riders would have come from noble birth, would have been fewer in number, and would have been selectively deployed.

Parthian Shiva-tir (Horse Archers) engaged in discharging their missiles (Source: Ancientbattles.com).

As a support system – if the horse archers were largely successful on their own – the role of the cataphract would be to intercept enemy cavalry and mop up remaining pockets of resistance and fleeing troops with their long lances and swords. As an offensive weapon, the heavy horse cataphract ran pell-mell into an enemy formation. Such a massive animal at top speed would, like a bowling ball, have scattered soldiers left and right, even causing those near the area of impact to be jostled. Multiple cataphracts attacking a formation at once would have had a devastating effect up and down a line of defense. Besides those directly killed or trampled: with bodies flying, fighters fleeing, and shields down, the cataphracts would have created gaps of vulnerability into which Parthian archers shot.

The Battle of Carrhae (53 BCE)

Smart with their tactics, the Parthians were also adept at psychological warfare. At the Battle of Carrhae, before the Romans approached, Surena, the Parthian general, hid the bulk of his force behind his advance guard so his army would appear small. Then, “to confound the soul and unseat judgment” (Crassus, 23:7) the Parthians filled the plain with a deafening beat of kettledrums. Plutarch mentions these drums were covered with bronze bells. As Valerii Nikonorov points out, like east Indian drums, the bells were probably inside the drum:

“… numerous and large, resounding with a buzz resembling the sound of a wild beast rather than the sound of a musical instrument” (72).

The Iranian Naqareh (a type of timpani) (Photo source: Beytoote) which like the Koos (a type of large bass drum) has been part of the inventory of the martial music of the armies of Iran in the pre- and post-Islamic eras.

Plutarch describes their sound:

“… like the bellowing of beasts mixed with sounds resembling thunder” (Crassus, 23:7).

The Iranian Koos (a type of large bass drum) which has been in Iranian armies since antiquity (Photo source: Tarafdari).

This alone caused consternation among the Romans. For the next step though, prior to the Romans’ advance, Surena had his cavalry cover their armor with skins and robes. Then after the Romans came closer, the Parthians spread out, uncovered their armor, and were suddenly seen by the Romans

“… blazing in helmets and breastplate; their Margianian steel glittering keen and bright” (Plutarch, Crassus, 24.1).

Reconstruction by Peter Wilcox and the late historical artist, Angus McBride of the Parthian Asbaran armored knights as they would have appeared in 54 BCE (Picture Source: Osprey Publishing). Large numbers of Asbaran attacking as a cohesive “armored fist” in coordination with the Parthian horse archers resulted in devastating striking power against Roman armies.

When it came to the battle itself, the Parthians would show how their light and heavy horse worked flexibly and in concert.

A reconstruction of Battle of Carrhae (53 BCE) entitled “Parthian Empire Vs Romans | Battle of Carrhae 53 BC | Historical Cinematic Battle” by the Total War battles venue (Source: TotalWarBattles in YouTube).

Though Surena thought at first to send his cataphracts to break the Roman lines, when he saw the depth of the Roman formation, with shields interlocked, he decided on missile bombardment. Surrounding the Romans, the Parthian horse-archers released an unmerciful barrage of arrows that tore through armor.

Parthian Horse archers engage the Roman legions of Marcus Lucinius Crassus at Carrhae in 53 BCE. Unlike the Achamenid-Greek wars where Achaemenid arrows were unable to penetrate Hellenic shields and armor, Parthian archery was now able to penetrate the armor and shields of their Roman opponents (Picture Source: Antony Karasulas & Angus McBride).

Thinking the Parthians might run out of ammunition, when Crassus, the Roman commander, saw Parthian camels coming with a fresh supply of arrows, he sent his son, Publius, at the head of cavalry and infantry to attack. The Parthian light horse then feigned retreat and after a long chase ran the Romans into an ambush of cataphracts. As the Romans halted, the Parthian light horse circled about and kicked up such a thick cloud of dust the Romans tightened their formation and were again easy targets. Finally, Publius charged the cataphracts, but with their superior armor, longer lances, and probably more skilled riders, the Parthians soon prevailed.

Map of the general campaign geography of the Battle of Carrhae (Source: Gates of Nineveh).

Confirming the purpose of the cataphract to break enemy lines with headlong impact to open gaps for Parthian archers, Cassius Dio relates this about Publius’ fiasco:

“In his eagerness for a victory he was separated far from his phalanx and was then caught in a trap and cut down. When this took place, the Roman infantry did not turn back, but valiantly joined battle with the Parthians to avenge his death. They accomplished nothing worthy of themselves because of the enemy’s numbers and tactics. If they decided to lock shields for the purpose of avoiding the arrows by the density of their array, the pike-bearers [cataphracts] were upon them with a rush, would strike some, and at least scatter the others: and if they stood apart, so as to turn these aside, they would be shot with arrows“. (40.21)

That day the Romans suffered one of their worst defeats. Publius died in battle. Crassus would later be executed. Few Romans would escape.

The late exemplary actor Sir Laurence Olivier’s (1907-1989) portrayal of Marcus Lucinius Crassus (115-53 BCE) in the epic movie “Spartacus (1960)” (Picture Source: Murph Place). Crassus’ dreams of conquering Parthian Persia and emulating Alexander ended in disaster at Carrhae in 53 BCE. Several decades after its release of “Spartacus”, Hollywood has yet to produce a “Crassus sequel” epic of the Roman statesman’s failure in Persia.

Garrisons and Logistics

While Parthia’s military strength lay in its horse archers and cavalry, giving it fluidity and range like no other, in other areas that required a constant presence, Parthia co-opted operations with its subject allies. While the Parthians were not known for their siegecraft, they did maintain garrisons at their borders. As Cassius Dio says,

“They dwell beyond the Tigris, possessing for the most part forts and garrisons, but also a few cities” (40.14).

In Mesopotamia at least, it appears they drafted Macedonian and Greek cooperation for the maintenance of their garrisons. On Crassus’ invasion of Parthia, his first act was to get “possession of the garrisons, and especially the Greek cities that were once controlled by Parthia as:

“… many of the Macedonians and of the rest that fought for the Parthians were Greek colonists” (40.13).

The Parthians were also wise not to stretch their supply lines. While they fought in terrain favorable to their cavalry, they were reluctant to fight under conditions that:

“… have no supplies of either food or pay.”

Moreover, where water was scarce, Cassius Dio says the Parthians conditioned themselves to endure scorching heat and developed survival techniques:

“… which helped them in repelling, without difficulty, the invaders of their land” (40.15).

Parthia’s Wars

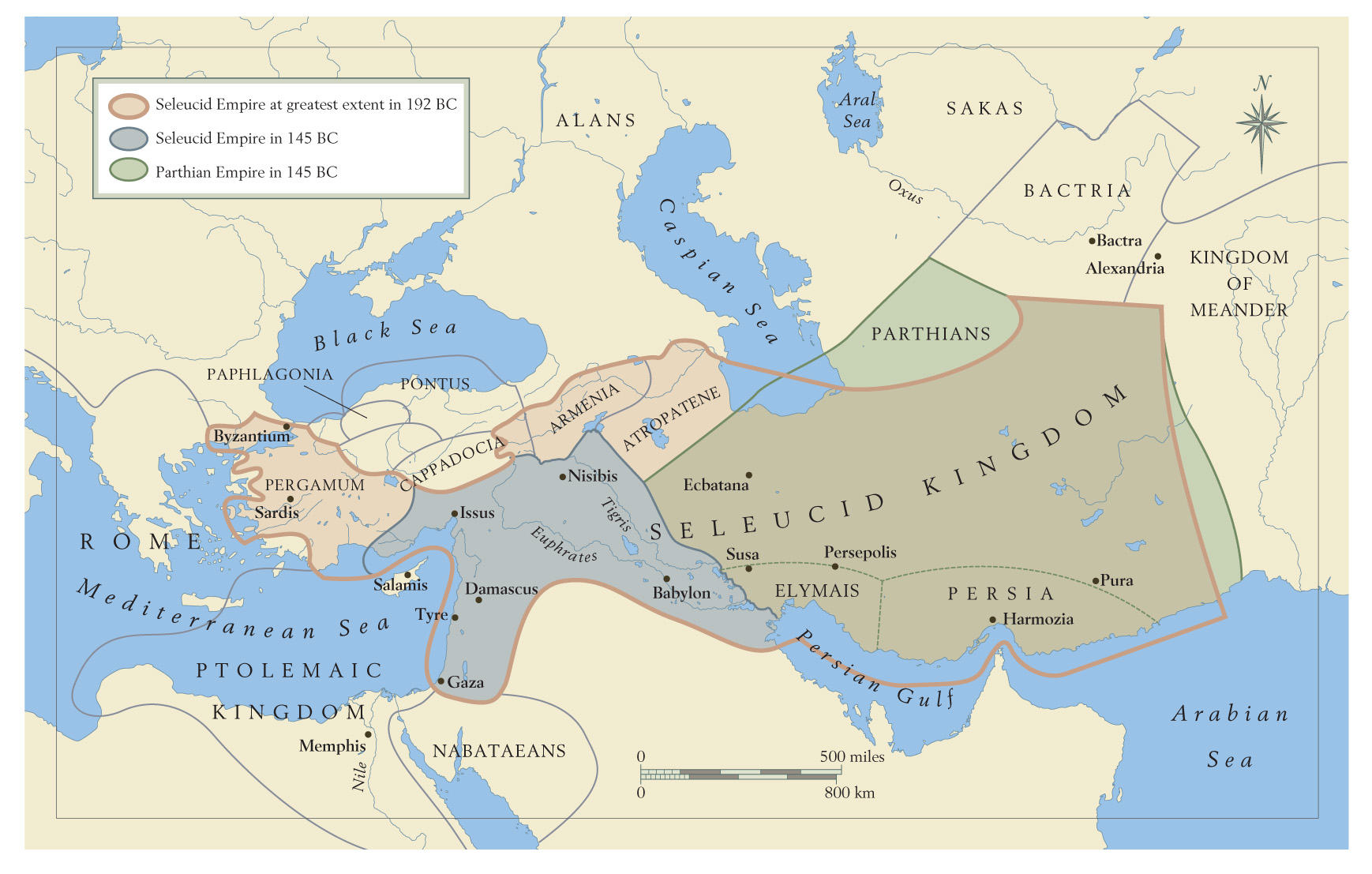

While few of Parthia’s military tactics are as documented like those at Carrhae, we can ascertain an outline of Parthia’s wars. One thing for sure, Parthia’s attaining and maintenance of its empire was not a meteoric rise. There were wins and losses along the way, even from the start. The takeover of the Seleucid Empire by the Parthians began in 247 BCE. While the Seleucids were weakened by internal war and conflict with the Ptolemies in the west, Arsaces, Parthia’s first king, saw an opening and conquered the province of Parthia, but the Seleucid ruler Antiochus III would retake Parthia in 209 BCE. Then, after Antiochus went back to Syria, and seeing Seleucid might reduced by the Treaty of Apamea with the Romans, the Parthians saw another opportunity.

Around 174 BCE, Phraates attacked the Seleucid Empire. By conquering the Amardians, Phraates gained the region between Hyrcania in the east and Media to the southwest, but it would be his brother Mithridates who would win many wars and much territory. Right away, he turned east to conquer Bactria – India and China’s neighbor – around 168 BCE. Then, he went west toward Media. Meeting stiff resistance in a nine-year war, Media was finally added to Parthia’s growing territorial advance in 151 BCE. After a four-year hiatus, possibly to reboot his military, Mithridates thought the time was ripe to look even further west toward the all-important fertile crescent area of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers known as Mesopotamia. Around 144 BCE he invaded and captured Seleucia, the former Seleucid capital. In 141 BCE he conquered Babylon. Able to fend off Demetrius II’s 138 BCE campaign to retake Seleucid territory, Mithridates then went south to take Elamite country and the capital city of Susa. However, wanting their territory back, the Seleucids again struck back at the Parthians.

Parthia and the Seleucid kingdom in circa 145 BCE (Picture source: Farrokh, 2007, page 119, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

Mithridates son, Phraates II (132-127 BCE) would kill Antiochus VII in battle but would die trying to put down a Scythian mutiny. After the death of Phraates II, uprisings in Parthian territory abounded. Uncle of Phraates II, Artabanus I (c. 127-124 BCE) would successfully put down revolts in Elam, Characene, and Babylon, but his reign was cut short when he was killed in battle against the Yuezhi in the east. His son, Mithridates II (124-88 BCE) would take over and become Parthia’s greatest ruler. Mithridates would not only strengthen Parthia’s hand in Elam, Characene, Mesopotamia, and Bactria, but he added Albania and Armenia and captured the Syrian city of Dura-Europas in the west. With frontiers now stretching between the Mediterranean Sea and China, Parthia became a geographical juggernaut and true superpower.

However, the Parthians would experience some serious challenges, this time from Rome. Phraates III (70-57 BCE) would lose Armenia, Albania, and Gordyene in northern Mesopotamia to the Romans, causing his sons to assassinate him. After civil war broke out, when Orodes II (57-37 BCE) killed his brother Mithridates III and reconquered the capital city of Seleucia, the time was yet ripe for perhaps Parthia’s greatest victories against the Romans. We touched on the rout of the Romans at Carrhae, which was avenged by the Romans in 38 BCE, when the Roman general, Ventidius defeated Orodes’ son, Pacorus in Syria.

The defeat of Mark Antony, two years later, would again prove the effectiveness of Parthia’s hit-and-run/non-engagement tactics. Under the pretext of getting the Roman standards back that were captured at Carrhae, Mark Antony began his campaign from Syria. Securing his position with the allegiance of surrounding kingdoms, he set out from Armenia on a mountain route for Media. His plan was to lay siege to the important fortress city of Phraaspa, make it a garrison, and from there attack Parthia. Impatient with the slow progress of the siege train, Mark Antony hastened on to Phraaspa to begin preliminary siege work while his convoy caught up. The Parthians attacked the convoy and defeated the two legions left to protect it. Finally, still unable to take Phraaspa and with winter coming on, Mark Antony accepted the offer of a truce by Phraates IV. The Parthians would harass the Romans during their retreat, causing the Romans to lose another 3,000 troops.

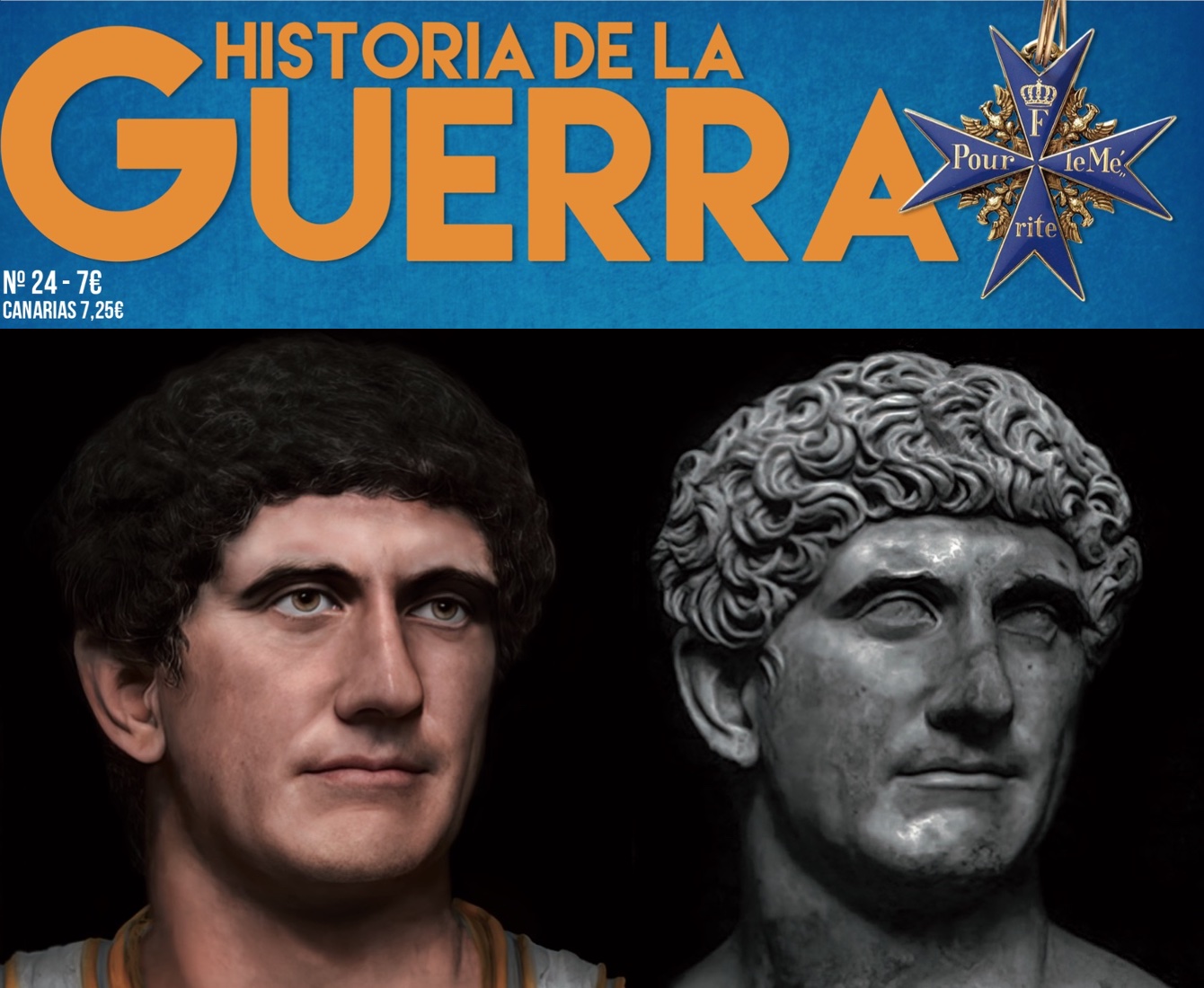

The above illustration at left of Roman statesman and military leader Marc Antony (83-30 BCE) is based on the marble bust [at right] in Rome (Vatican Museums, Chiaramonti Museum). This was published in the 24th edition (summer 2021) of the Spanish military history journal “Historia de la Guerra” (download in Academia.edu: Farrokh, K., & Sánchez-Gracia, J. (2021). La campaña Parta/Persa de Marcon Antonio [The Parthian/Persian campaign of Marc Antony]. Historia de la Guerra, 24, pp.5-12.). Antony’s expedition into ancient Praaspa (near modern Tabriz)ended in disaster in 36 BCE mainly at the hands of Iranian Parthian armored knights and horse-archers. In one of the engagements, 10,000 Roman legionnaires were destroyed. Marc Antony and his surviving troops fled into Armenia, then Syria and from there to Egypt where Ptolemid Queen Cleopatra provided them sanctuary and shelter (For more details consult Farrokh, 2007, pages 144-146, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

With the victories over Crassus and Mark Antony, followed by a peace agreement with the Romans in 20 BCE, the Parthians might have thought their empire was secure, but in almost domino fashion, external invasions and internal dissension would take their toll. Though Artabanus II (10-38 CE) successfully dealt with provincial rebellion and won a struggle for control with his brother, Vonones II, outside pressure at Parthia’s eastern and western frontiers were on the horizon. In the west, in 115 CE, the Roman emperor Trajan invaded Parthia conquering Mesopotamia and looting the capital cities of Seleucia and Ctesiphon.

Then in the east, supporting the oriental record of war between the Parthians and Kushans, the Kushan warlord, Kanishka (120-144 BCE) would establish his empire in Bactria, what was once Parthia’s easternmost province. Back west, though the forces sent by Trajan were withdrawn, Rome would come at Parthia again in 165 CE, during Vologases IV’s reign (147-191 CE).

Statue of King Kanishka I (c. AD 127–163) of the Kushan Empire (c. 30-375 CE) (housed in the Mathura Government Museum, India; Source: Public Domain). The large broadsword was a powerful cultural symbol in the martial cultures of the Iranian kingdoms as exemplified by the “broadsword” of Khosrow II seen at the top panel inside the Iwan at Taghe Bostan near Kermanshah in Western Iran.

The emperor Lucius Verus would win several battles and sack Seleucia and Ctesiphon once more. Somehow the Parthians managed to expel the Romans, but the Romans returned in 198 CE. Though the emperor Septimius Severus had to leave because of a shortage of food, Mesopotamia would be devastated for the third time in a short 83 years, and the Parthian Empire would be severely weakened. Finally, after Artabanus IV (213-224 CE), king of Media rebelled against his brother Vologasus VI (208-213 CE) precedent was set for a severely weakened Parthia to be entirely overthrown by another rebel king, Ardashir, founder of the Sassanian Empire in 224 CE.

The three-day Battle of Nisibis (summer 217 CE) fought between Roman emperor Macrinus and the Parthian army of King Artabanus IV (Source: Fall3nairborne.Deviantart,com for Pinterest). Macrinus failed to defeat the Parthians, obliging him to negotiate a peace settlement by paying them fifty million Dinars as well as gifts. This also signaled the end of Caracalla’s attempted invasion of Mesopotamia the previous year.