Kindly note that the images and accompanying captions for Figures 9a-9b, 11, 12 and 13 printed below do not appear in the Encyclopedia Iranica publication. In addition the accompanying caption for Figure 10 does not appear in the original Encyclopedia Iranica publication.

Readers are also referred to the following articles for download from Academia.edu:

- Farrokh, K. (2009). The Winged Lion of Meskheti: a pre- or post-Islamic Iranian Legacy in Georgia? Scientific Paradigms. Studies in Honour of Professor Natela Vachnadze. St. Andrew the First-Called Georgian University of the Patriarchy of Georgia. Tbilisi, pp. 455-492.

- Sheda Vasseghi (2017). Positioning Of Iran And Iranians In Origins Of Western Civilization. PhD Dissertation, University of New England, Academic advising Team: Marylin Newell, Laura Bertonazzi, Kaveh Farrokh.

- Farrokh, K. (2016). An Overview of the Artistic, Architectural, Engineering and Culinary exchanges between Ancient Iran and the Greco-Roman World. AGON: Rivista Internazionale di Studi Culturali, Linguistici e Letterari, No.7, pp.64-124.

For more information on ties between Iran, the Caucasus and Europe consult:

- Iran & Caucasia

- Eire-An (Greater Iran) & Europa

- Zoroastrian and Mithraic Sites of the Caucasus

- UBC Lecture (November 29, 2019): Civilizational Contacts between Ancient Iran and Europe

================================================================

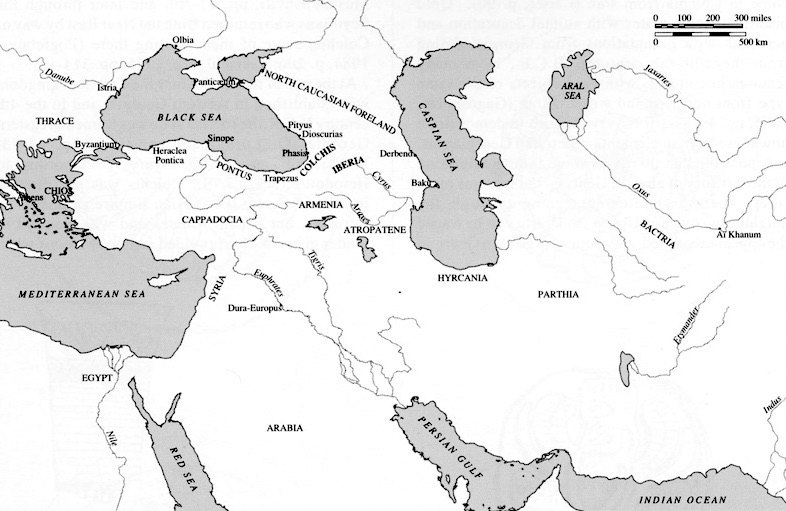

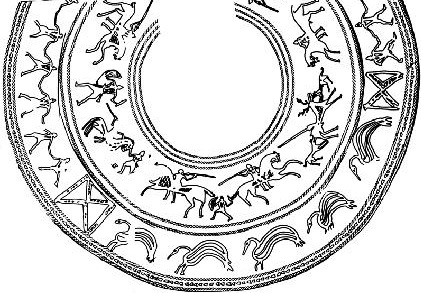

Ancient Georgian tribes had close cultural contacts with Near Eastern civilizations from the 18th century B.C.E. (Figures 1-2), as evidenced by the gold figurine of a stag (Sumerian influence) and the silver bowl with two friezes of relief decoration of a procession, and “tree of life” and animals (Hittite artistic traditions) from the Trialeti mound (Miron and Orthmann, pp. 30, 32). Iranian elements appeared from the middle of the 2nd millennium B.C.E., as they did in the art of the entire Caucasian region. Some objects, such as a bronze rhyton from eastern Georgia (Miron and Orthmann, p. 270, n. 196) were brought from the territory of ancient Iran, while bronze animal- and disc-headed pins, as well as pendant bells and openwork birds, were derived from ancient Iranian styles (Miron and Orthmann, pp. 248, 264-66). Daggers, swords, axes, adzes, pick-axes, and bidents also have close Iranian parallels (Miron and Orthmann, pp. 243-45, 322-24; Moorey, pls. 1-7; Haerinck, pl. 65).

Figure 1: Map of the Caucasus Iran and the Near east in the 18th century BCE (Encyclopedia Iranica).

Iranian elements continued to appear in weapons, horse harnesses, and bronze ornaments until the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 1st millennium B.C.E. (Pogrebova, 1977, pp. 33-84; Tsetskhladze, 1999, pp. 478-82), but the vast majority of objects date from the 8th-7th centuries B.C.E. when the influence of the Luristan bronzes is clearly noticeable (Pogrebova, 1984). On bronze belts there are fantastic animals, people, and hunting scenes (Miron and Orthmann, pp. 118-19, 286-87; Urushadze, pp. 128-35; Mikeladze, 1995), and the image of two animals facing one another is found on pendants (Miron and Orthmann, p. 249; Pogrebova, 1984, p. 133).

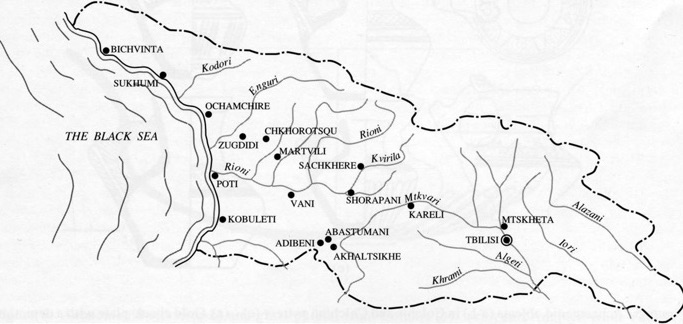

Figure 2. Schematic map of Georgia showing principal archaeological sites. After Kacharava, p. 79, fig. 1 (Encyclopedia Iranica).

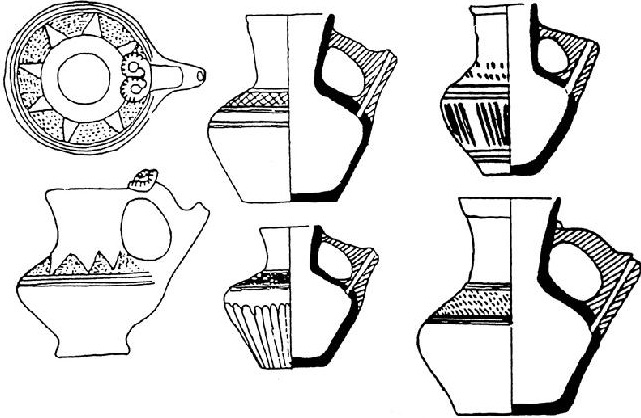

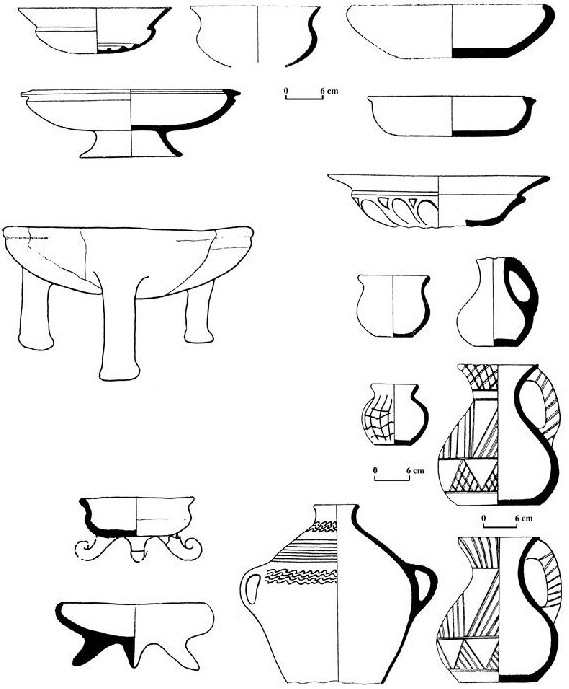

From Vani (western Georgia) originate clay figurines of two- or three-headed fantastic animals, animal-headed axes, etc. (Miron and Orthmann, pp. 144, 284, n. 230; Mikeladze, 1990, pl. xviii; Lordkipanidze, 1995, pp. 41-48; Moorey, p. 233; Muscarella, pp. 270-72). In this period a very distinctive shape of pottery, namely jugs with tubular handles (Mikeladze, 1990, pl. xv; Figure 3), which is well-known from northwestern Iran (Ghirshman, p. 128; Dyson, 1965, fig. 7; Tuba Ökse, pp. 55, 59), appeared in Colchis (western Georgia).

Figure 3: Jugs with tubular handles. After Mikeladze, 1990, Table XV (Encyclopedia Iranica).

Another type of pottery, legged pots with wave ornament, must also have come to Colchis from Iran (Carter, p. 90). Gold beads, earrings, plates with animal decoration and pendants with granulations from Georgia, dating from the 10th-6th centuries B.C.E., have many features in common with gold objects of the same type from northern and western Iran (Gagoshidze, 1985, pp. 48-57). It is very difficult to demonstrate how these Iranian elements penetrated Georgian art. It is possible that there was some Iranian migration to the territory of ancient Georgia, but it seems more likely that these elements came through the neighboring state of Urartu (to Urartu can be traced the appearance of red-clay pottery in eastern Georgia; Muskhelishvili, pp. 17-30), and later through the Scythians who returned from the Near East by way of Colchis, some of them settling there (Pogrebova, 1984, p. 206; Tsetskhladze, 1995, pp. 314-15).

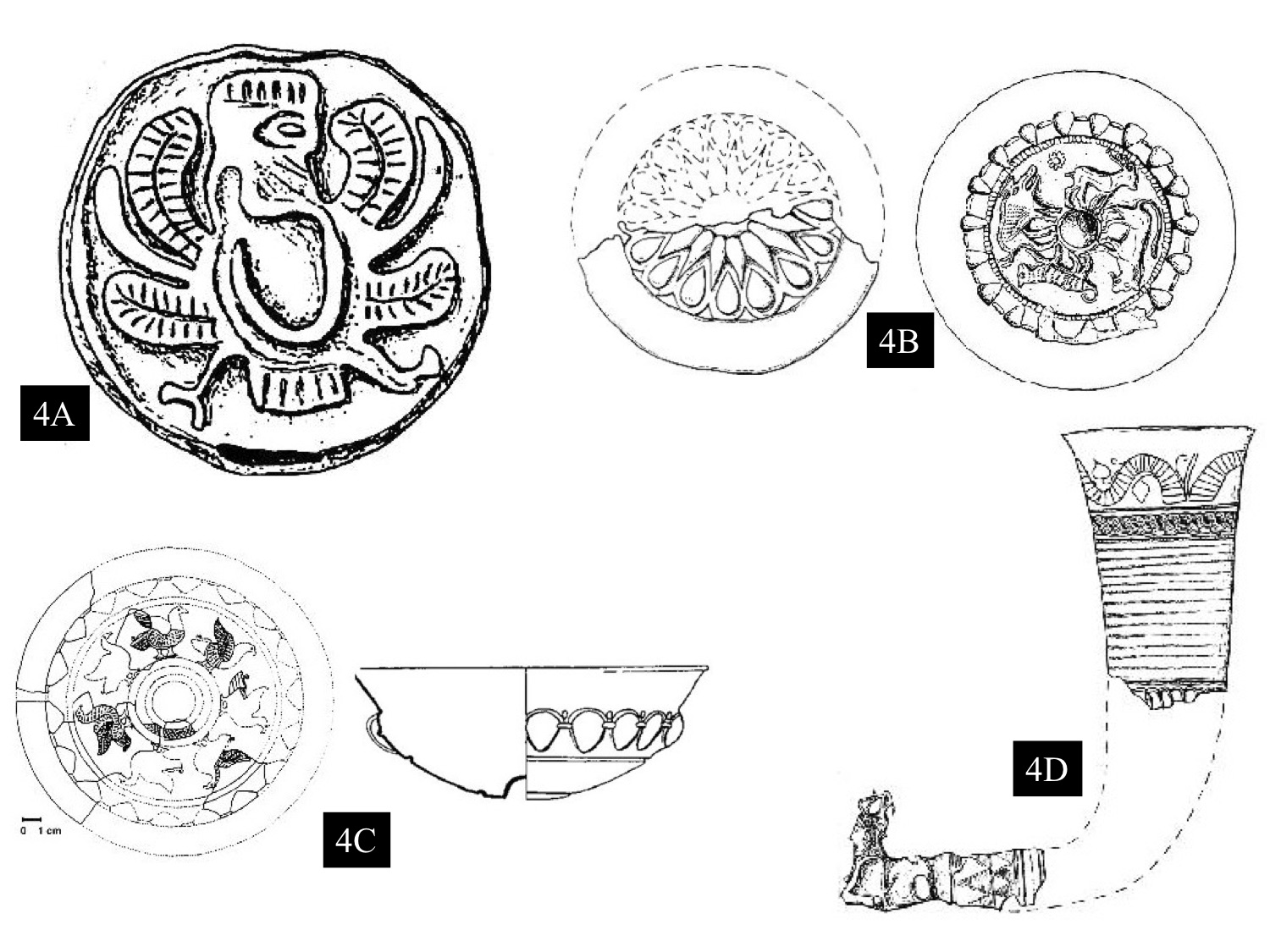

At the end of the 6th century the Colchian kingdom was established in western Georgia, and in the 4th century B.C.E. the Iberian state was formed in eastern Georgia (O. Lordkipanidze, 1979, pp. 48-73; Melikishvili, pp. 245-60; Figure 3, above). According to Herodotus (3.97, 7.79), Colchis was not directly incorporated into the Persian Empire as one of its satrapies, but it paid tributes and was required to render gifts. It also provided auxiliary troops when required to do so. Probably, Colchis was used by Persians as a buffer state between their empire and the nomads of the southern Caucasus; Persian kings gave luxurious diplomatic gifts (Tsetskhladze, 1993-94, pp. 26-31; cf. Herodotus, 3.20-21, 7.116, 9.20; Xenophon, Anabasis 1.2.27, 1.8.28-29; idem, cyropaedia 8.2.7, 8.3.1, 8.3.3) to the Colchian rulers and elite. This is witnessed by the finds in the rich graves of the local elite in Vani and Sairkhe: gold Achaemenid bracelets, earrings, a pectoral, a phiale and bridle ornaments (three round cheek-plates with schematic depictions of Ahura Mazdā; (Figure 4a; see Nadiradze, pp. 55-57), silver phialai (Figure 4b, Figure 4c), cups, a jug and a rhyton Figure 4d), a glass perfume-bottle and phiale (Makharadze and Saginashvili), bronze and iron armor, bridle bits, etc. (Gigolashvili). All of these date from the middle 5th to early 3rd century B.C.E. and were probably manufactured in one of the satrapal production centres. Gold diadems from Vani have plaques with relief scenes of animals fighting, a motif so common in Iranian art (Tsetskhladze, 1993-94, pp. 11-49 with illustrations). These burials also contain seals and gems in the Graeco-Persian style (M. Lordkipanidze, 1975, pp. 109-12).

Figures 4A-4d: Achaemenid objects in Colchis – [Figure 4A] gold cheek-plate with a depiction of Ahura Mazdā (Sairkhe). Adapted from Nadiradze, Table V, 3.; [Figure 4B] Achaemenid silver phiale from Colchis. Vani. Adapted from Vani IV, figs. 199, 202; [Figure 4C] Achaemenid silver phiale from Colchis. Environs of Dioscuria. After Kvirkvelia, p. 81, fig. 21; [Figure 4D] Achaemenid objects in Colchis: silver rhyton Mtisdziri, environs of Vani. Adapted from Gamkrelidze, fig. 21 (Encyclopedia Iranica).

Excavation of Sairkhe yielded a stone Doric capital decorated in relief with broad water lily leaves (Kipiani, pp. 15-22; Shefton, pp. 179-86; Figure 5).

Figure 5: Architectural remains from Colchis (Sairkhe): Doric capital. After Kipiani, Tables X.1 (Encyclopedia Iranica).

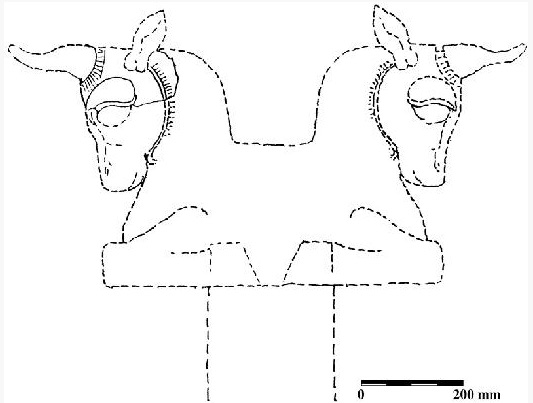

Another capital, a bull-protome, was found at Sairkhe (Kipiani, pp. 12-15; Figure 6).

Figure 6: Architectural remains from Colchis (Sairkhe): bull-protome. After Kipiani, Table IX.2 (Encyclopedia Iranica).

Both capitals date from the 5th-4th centuries B.C.E. and probably indicate the presence of some Achaemenid architects who decorated buildings for the local elite in the style of Persian court art. A 3rd century B.C.E. stamp on Colchian amphorae, representing the impression from a seal and depicting a horseman with a star, the crescent moon, and bird, demonstrates the penetration of the cult of Mithras into Colchis (Tsetskhladze, 1992, pp. 115-22). From the 4th century B.C.E. jar burials began to appear in Colchis and throughout Transcaucasia including Iberia, which may serve as an indication of Achaemenid expansion in this region (Noneshvili, pp. 12-54).

The culture of Iberia shows a much stronger Achaemenid influence than Colchis does. Although it is not clear whether Iberia was part of one of the satrapies of the Achaemenid Empire (Cook, pp. 78-79), archeological material enables us to suppose that it was. Some scholars, not without grounds, suppose the existence of local Iberian Achaemenid provincial workshops for the production of metal objects, including jewelry (Gagoshidze, 1996). It is possible that the so-called palace of the 5th-4th centuries B.C.E. with Achaemenid stone column bases (Furtwängler, pp. 190-91, figs. 10-11), which has been investigated in Gumbati, was the residence of the local Iberian satrap (Knauss, pp. 85-92). The well-known Akhalgori treasure, as well as treasures from Tsinskaro and Kazbegi, contain many Achaemenid objects (Smirnow, pp. 5-20; Survey of Persian Art, Pls. 118-19; Melikishvili, pp. 248-50). Achaemenid phialai are found in rich burials (Gagoshidze, 1964, pp. 66-69). Excavation of recent years has yielded glass perfume-bottles as well (Kacharava, p. 85, fig. 11). Ancient Iranian silver and clay vessels had a strong influence on Iberian local pottery. Clay imitations of Achaemenid phialai and rhytons are found at many sites (Narimanishvili, pp. 47-50; Gagoshidze, 1979, pp. 81-84; Furtwängler, pp. 197-98, figs. 13.3, 14.1; Figure 7).

Figure 7: Iberian pottery of the 6th-1st centuries B.C.E. Adapted from Narimanishvili, passim, and Gagoshidze, 1981, passim (Encyclopedia Iranica).

From the 4th century B.C.E. large and small red painted vessels became widespread; they were decorated with animals, hunting and fighting scenes, geometric patterns (this type of pottery is also known from the Colchian hinterland not far from the Iberian border; Miron and Orthmann, pp. 133, 159-60; Gagoshidze, 1979, pp. 88-95; Narimanishvili, pp. 69-79; see Figure 8).

Figure 8: Material from Samadlo: red painting on pythos. After Gagoshidze, 1981 (Encyclopedia Iranica).

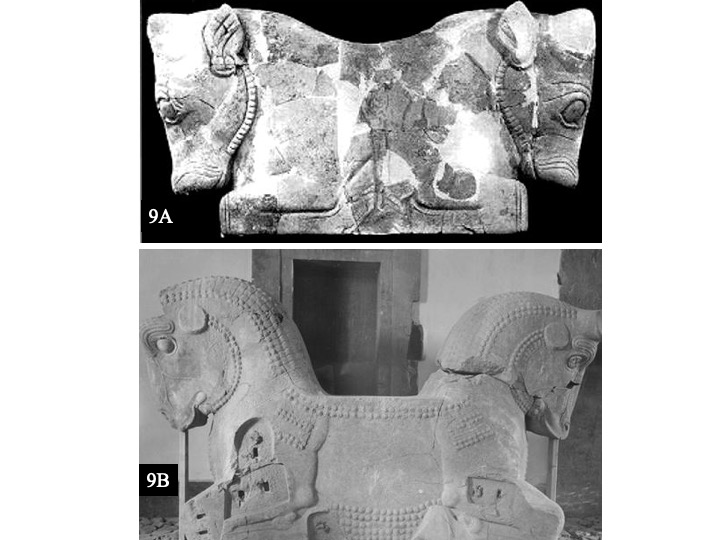

The shape of pottery jugs with pairs of animal handles is another indication that Iberia was one of the Achaemenid satrapies in the classical period (Narimanishvili, pp. 282-83; Figure 11). This shape survived in Iberia until the 1st century B.C.E., e.g., the ram-shaped handle from Samtavro (Miron and Orthmann, p. 171). It is thought that in the 5th century B.C.E. there were special workshops that produced gems in the Achaemenid style (M. Lordkipanidze, p. 116). The architecture of Iberia provides further examples of the presence of Iranian elements. Examples include a bull-protome capital from Tsikhia Gora (see Figures 9a-9b below).

Figure 9A: Ancient Georgian Column Capital discovered in Tsikhia Gora (Source:Gagoshidze and Kipiani). Note the striking resemblance to the column capital from Persepolis below; Figure 9B: The double-bull motif column capital typical of Achaemenid-era architecture in sites such as Persepolis and Susa. Note the vivid parallels in style, construction and motifs to its Georgian counterpart. Architecture is only one of the many facets in which the ancient Caucasus and Persia have enjoyed mutual influences (Pictures and captions from Kaveh Farrokh’s lectures at the University of British Columbia’s Continuing Studies Division and were also presented at Stanford University’s WAIS 2006 Critical World Problems Conference Presentations on July 30-31, 2006).

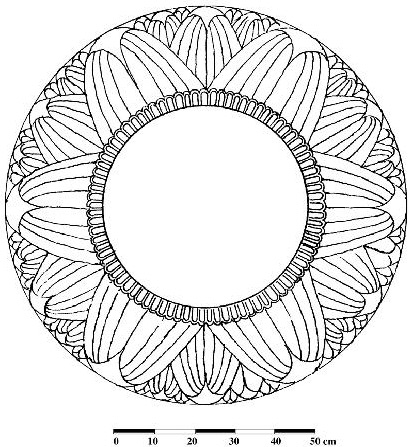

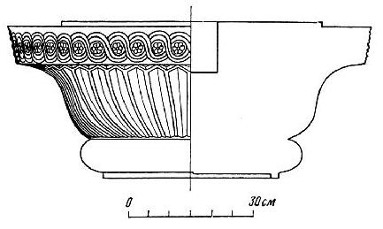

Other examples are capitals decorated in relief with lotus leaves from Dedoplis Mindori (Figure 10), Shiogvime, and Sarkine, all of which date from the Hellenistic period (Kipiani, pp. 6-11, 49-58; Miron and Orthmann, p. 170).

Figure 10: Architectural remains from ancient Iberia, Dedoplis Mendori (Source: Encyclopedia Iranica). As expostulated by Kaveh Farrokh at the lectures at Yerevan State University [YSU] (Nov. 4, 2013) the area features a complex of ten temples which Gogoshidze (1992) and Kipiani (1987, 2000) interpret as local Zoroastrian fire temples. As further averred by Kaveh Farrokh at the YSU lectures, the capital’s bell-type shape had been built with the assistance of [as quoted from Tsetskhladze] “…Achaemenid architects who decorated buildings for the local elite in the style of the Persian court” (2001, pp.474).

It is thought that the capitals were used in temples dedicated to fire-worship (Gagoshidze, 1979, pp. 21-23; Kimsiasvili and Narimanisvili). Excavation in Dedoplis Mindori yielded even more important material dating from the 1st-2nd centuries C.E., including a royal palace complex with a temple complex where fire was worshipped (Figure 8c) and bone plates for playing cards, with depictions of animals, hunting scenes, and Aramaic inscriptions (Gagoshidze, 1992, pp. 27-48; Figure 12). Another temple for fire-worship was found in Samadlo, dating from the 4th-2nd centuries B.C.E. (Gagoshidze, 1979, pp. 25-30, 65-66). An important find there was limestone fragments with relief scenes of mounted hunters pursuing a ram (Figure 9b). Stylistically, it probably belongs to the end of the Achaemenid period. This relief was used to decorate either the walls of a monumental building or an altar in a temple for fire-worship (Gagoshidze, 1979, pp. 65-66; idem, 1981, pl. xix, no. 236). Iranian elements are visible also in palace architecture, e.g., in Mtskheta, capital of the Iberian kingdom, where capitals in the royal palace show Iranian influence (Lezhava, pl. lix, no. 5; Figure 8d).

Figure 11: Panoramic view of the interior of the Atashgah (Zoroastrian fire temple) of Tbilisi (Source: Dr. Nadir Gohari, 2017).

From the first centuries C.E., the cult of Mithras and Zoroastrianism were commonly practiced in Iberia. Excavation of rich burials in Bori, Armazi, and Zguderi has produced silver drinking cups with the impression of a horse either standing at a fire-altar or with its right foreleg raised above the altar (Machabeli, pls. 37, 51-54, 65-66). The cult of Mithras, distinguished by its syncretic character and thus complementary to local cults, especially the cult of the Sun, gradually came to merge with ancient Georgian beliefs. It is even thought that Mithras must have been the precursor of St. George in pagan Georgia (Makalatia, pp. 184-93). Step by step, Iranian beliefs and ways of life penetrated deeply the practices of the Iberian court and elite: the Armazian script and “language,” which is based on Aramaic (see Tsereteli), was adopted officially (a number of inscriptions in Aramaic of the Classical/Hellenistic periods are known from Colchis as well; Braund, pp. 126-27); the court was organized on Iranian models, the elite dress was influenced by Iranian costume, the Iberian elite adopted Iranian personal names (Braund, pp. 212-15), and the official cult of Armazi (q.v.) was introduced by King Pharnavaz in the 3rd century B.C.E. (connected by the mediaeval Georgian chronicle to Zoroastrianism; Apakidze, pp. 397-401).

Figure 12: A Georgian portrayal of the legendary King Pharnavaz of Georgia who was the king of Karli in the 3rd century BCE. Kartli was identified as Iberia by the Classical sources (Source: Burusi). According to the Georgian Chronicles (royal annals, page of edition 25, line of edition 4): “…Pharnavaz made all and everything alike the Kingdom of the Persians”. It has been suggested that Pharnavaz based his administration upon an Iranian system (see Rapp, Stephen H., Studies In Medieval Georgian Historiography: Early Texts And Eurasian Contexts. Peeters Bvba, 2003, p.275).

Iranian elements in ancient Georgian art and archeology gradually ceased from the 4th century C.E. when Christianity became the official religion of the Georgian states.

Figure 13: Images of Georgian Queen Tamar and King David II (1089-1125; known as “Aghmashenebeli” [the builder]) in the Sveti Cathedral in Georgia. David II, who was a key figure in Georgia’s political-cultural reawakening, was a vigorous patron of Persian poetry. In this endeavor he established a school for promotion of Persian in the Caucasus. David II’s patronage of Persian literature resulted in the introduction of the following works of Persian poets into Georgian society: Rudaki (858-941), Nezami Ganjavi (1141-1209) and Firdowsi (935-1020) (Photo: Public Domain).

Bibliography

A. M. Apakidze, “Kul’tura Gruzii v antichnuyu epokhu: Iberiya” (Culture of Georgia in ancient times: Iberia), in G. A. Melikishvili and O. D. Lordkipanidze, eds., Ocherki istorii Gruzii (Essays on the history of Georgia) I, Tbilisi, 1989, pp. 393-448.

D. Braund, Georgia in Antiquity, Oxford, 1994.

E. Carter, “Bridging the Gap between the Elamites and the Persians in Southeastern Khuzistan,” in H. Sancisi-Weerdenburg, A. Kührt, and M. C. Root, eds., Achaemenid History VIII: Continuity and Change, Leiden, 1994, pp. 65-95.

J. M. Cook, The Persian Empire, New York, 1983.

R. H. Dyson, “Problems of Protohistoric Iran as Seen from Hasanlu,” JNES 24/3, 1965, pp. 193-217.

A. Furtwängler, “Gumbati: Archäologische Expedition in Kachetin 1994.

1: Vorbericht mit Beiträgen von A. Egold und F. Knauss,” Eurasia Antiqua 1, 1995, pp. 177-212.

Yu. M. Gagoshidze, Pamyatniki ranne antichnoĭ epokhi iz Ksanskogo ushchel’ya (Monuments of the classical period from the Ksan Gorge), Tbilisi, 1964.

Idem, Samadlo (arkheologicheskie raskopki) (Samadlo [Archeological excavation]), Tbilisi, 1979.

Idem, Samadlo: Katalog arkheo logicheskogo materiala (Samadlo: Catalogue of archeological material), Tbilisi, 1981.

Idem, “Iz istorii yuvelirnogo dela v Gruzii” (From the history of jewelry in Georgia), in V. G. Lukonin, ed., Khudozhestvennye pamyatniki i problemy kyl’tury Vostoka (Artistic monuments and problems of culture of the Orient), Leningrad, 1985, pp. 47-61.

Idem, “The Temples at Dedoplis Mindori,” East and West 42, 1992, pp. 27-48.

Idem, “The Achaemenid Influence in Iberia,” Boreas 19, 1996, pp. 125-36. G. Gamkrelidze, Tsentraluri Kolkhetis dzveli namosakhlarebi (Ancient settlement of the central Colchis), Tbilisi, 1982.

R. Ghirshman, The Arts of Ancient Iran, New York, 1964. N. Gigolashvili, “The Silver Aryballos from Vani,” in G. R. Tsetskhladze, ed., Ancient Greeks West and East, Leiden, Boston, and Cologne, 1999, pp. 605-13.

E. Haerinck, “The Iron Age in Guilan: Proposal for a Chronology,” in J. Curtis, ed., Bronzeworking Centres of Western Asia c. 1000-539 B.C., London and New York, 1988, pp. 63-78.

D. Kacharava, “Archaeology in Georgia 1980-90,” Archaeological Reportsfor 1990-1991, Athens, 1991, pp. 79-86.

K. Kimsiasvili and G. Narimanisvili, “A Group of Iberian Fire Temples (4th Cent. B.C.-2nd Cent. A.D.),” AMI 28, 1995-96, pp. 309-18.

G. Kipiani, Kapitelebi (Capitals), Tbilisi, 1987.

G. I. Lezhava, Antikuri khanis sakartvelos arkitekturuli dzeglebi (Architectural monuments of Georgia of ancient times), Tbilisi, 1979.

F. S. Knauss, “Achämeniden in Transkaukasien,” in S. Lausberg and K. Oekentrop, eds., Fenster zur Forschung, Münster, 1999, pp. 81-114.

G. Kvirkvelia, “On the Early Hellenistic Burials of North-Western Colchis,” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1, 1995, pp. 75-82.

M. Lordkipanidze, Kolkhetis dz. ts. V-III ss. sabechdavi-bechdebi (Colchian signet-seals of the 5th-3rd centuries B.C.E.), Tbilisi, 1975.

Idem, Udzvelesi sabechdavi-bechdebi iberiidan da kolkhetidan (Ancient signet-seals from Iberia and Colchis), Tbilisi, 1981.

O. D. Lordkipanidze, Drevnayay Kolkhida (Ancient Colchis), Tbilisi, 1979.

Idem, “Über zwei Funde aus Vani,” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1, 1995, pp. 41-52.

K. Machabeli, Dzveli sakartvelos vertskhli (Silver of ancient Georgia), Tbilisi, 1983.

S. Makalatia, “Gvtaeba Mitras kulti sakartveloshi” (The cult of the God Mithras in Georgia), Soobshcheniya Gosudarstvennogo Museya Gruzii (Bulletin of the State Museum of Georgia) 3, 1927, pp. 176-98.

G. Makharadze and M. Saginashvili, “An Achaemenian Glass Bowl from Sairkhe, Georgia,” Journal of Glass Studies 41, 1999, pp. 11-17.

G. A. Melikishvili, “Obrazovanie Kartliiskogo (Iberiiskogo) gosudarstva” (Formation of the Kartlian [Iberian] State), in G. A. Melikishvili and O. D. Lordkipanidze, eds., Ocherki istorii Gruzii (Essays on the history of Georgia) I, Tbilisi, 1989, pp. 245-60.

T. K. Mikeladze, K arkheologii Kolkhidy (On the archeology of Colchis), Tbilisi, 1990.

Idem, “Grosse Kollektive Grabgruben der frühen Eisenzeit in Kolchis,” Archäologischer Anzeiger 1, 1995, pp. 1-22.

A. Miron and W. Orthmann, eds., Unterwegs zum goldenen Vlies: Archäologische Funde aus Georgien, Saarbrücken, 1995.

P. R. S. Moorey, Catalogue of the Ancient Persian Bronzes in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1971.

O. W. Muscarella, Bronze and Iron: Ancient Near Eastern Artifacts in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1989.

D. L. Muskhelishvili, “K voprosu o svyazyakh Tsentral’nogo Zakavkaz’ya s Peredinim Vostokom v ranneantichnuyu epokhu” (On the links of Central Transcaucasia with the Near East in the early ancient period), in O. D. Lordkipanidze, ed., Sakatvelos arkheolgiis sakitkhebi (Questions of Georgian archeology) I, Tbilisi, 1978, pp. 17-30).

O. Nadiradze, Sairkhe Sakaretvelos udzvelesi kalaki (Sairkhe, ancient city of Georgia), Tbilisi, 1990.

G. K. Narimanishvili, Keramika Kartli V-I vv. do n.e. (Pottery of Kartli in the 5th-1st centuries B.C.E.), Tbilisi, 1991.

A. I. Noneshvili, Pogrebal’nye obryady narodov Zakavkaz’ya (Burial rites of the people of Transcaucasia), Tbilisi, 1992.

M. N. Pogrebova, Iran i Zakavkas’e v rannem zheleznom veke (Iran and Transcaucasia in the Early Iron Age), Moscow, 1977.

Idem, Zakavkaz’e i ego svyazi s perednei Aziei v skifskoe vremya (Transcaucasia and its contacts with Near Asia in the Scythian period), Moscow, 1984.

B. B. Shefton, “The White Lotus, Rogozen and Colchis: The Fate of a Motif,” in J. Chapman and P. Dolukhanov, eds., Cultural Transformations and Interactions in Eastern Europe, Aldershot, U.K., 1993, pp. 178-210.

J. I. Smirnow, Der Schatz von Achalgori, Tbilisi, 1934.

K. Tsereteli, “Armazuli damtserloba (Armazian Script),” Semitologiuri dziebani (Semitic studies) 5, Tbilisi, 1991, pp. 60-70.

G. R. Tsetskhladze, “The Cult of Mithras in Ancient Colchis,” Revue de l’histoire des religions 209, 1992, pp. 115-24.

Idem, “Colchis and the Persian Empire: The Problems of Their Relationship,” Silk Road Art and Archaeology 3, 1993-94, pp. 11-49.

Idem, “Did the Greeks Go to Colchis for Metals?” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 14, 1995, pp. 307-32.

Idem, “Between West and East: Anatolian Roots of Local Cultures of the Pontus,” in idem, ed., Ancient Greeks West and East, Leiden, Boston, and Cologne, 1999, pp. 469-96.

A. Tuba Ökse, “Imamoglu in der Eisenzeit: Keramik,” Istanbuler Mitteilungen 42, 1992, pp. 48-63.

N. Urushadze, “The Caucasian Bronze Belt,” The Bulletin of The Cleveland Museum of Art 81/5, 1994, pp. 128-39.

Vani IV: Arkheologiuri gatkhrebi (Vani IV: Archeological excavations), Tbilisi, 1979.