Kindly note that the images and accompanying captions printed below do not appear in the original Encyclopedia Iranica publication.

Readers are also referred to the following Resources:

- Cyrus the Great & The Cyrus Cylinder

- Farrokh, K., & Farhid, T. (1396/2018).[استوانه کوروش بزرگ و اسناد “دیگر” در بابل, مصر و ستون سنگی یادبود خانتوس] “Other” Cylinders and Records before and after Cyrus the Great: Kelar, Babylon, Egypt and Xanthus. Studies in Honor of Professor Jalal Khaleghi Motlagh (ed. F. Aslani & M. Pourtaghi), Tehran: Morvarid Publications, pp.379-394.

=================================================================================

Early History

The most significant chapter in the story of Jews and Judaism in Persia began 15 March 597 BCE, when King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylonia conquered Jerusalem and carried away as captives 10,000 Jews from Jerusalem and Judah, including King Jehoiachin of Judah. The archives of the British Museum in London store contemporaneous Babylonian chronicles written on clay tablets that describe the events, with which the Hebrew Bible concurs (Wiseman, pp. 32-33; 72-73). 2 Kings 24:14-16 states that the 10,000 Jews who were carried away included 7,000 warriors and 1,000 skilled workers. Esther 2:5-6 explains that Mordecai, who eventually became prime minister to the Persian King Ahasuerus (probably Xerxes I) at Susa was the great-grandson of Kish, who was one of those 10,000 captives. These prisoners were put into royal service, which included the development of new towns in places not previously inhabited, and military service. The Babylonian monarch appointed King Jehoiachin’s uncle, Zedekiah, King of Judah. When Zedekiah himself asserted his independence, Nebuchadnezzar again laid siege to Jerusalem and carried away more men, women, and children, and he destroyed the Temple. In due course, many of these people and their descendants would find their way to Persia, just as did the grandparents of Mordechai and Esther. Consequently, Haman was able to report that there were Jews in all the provinces of Persia (Esth. 3:8).

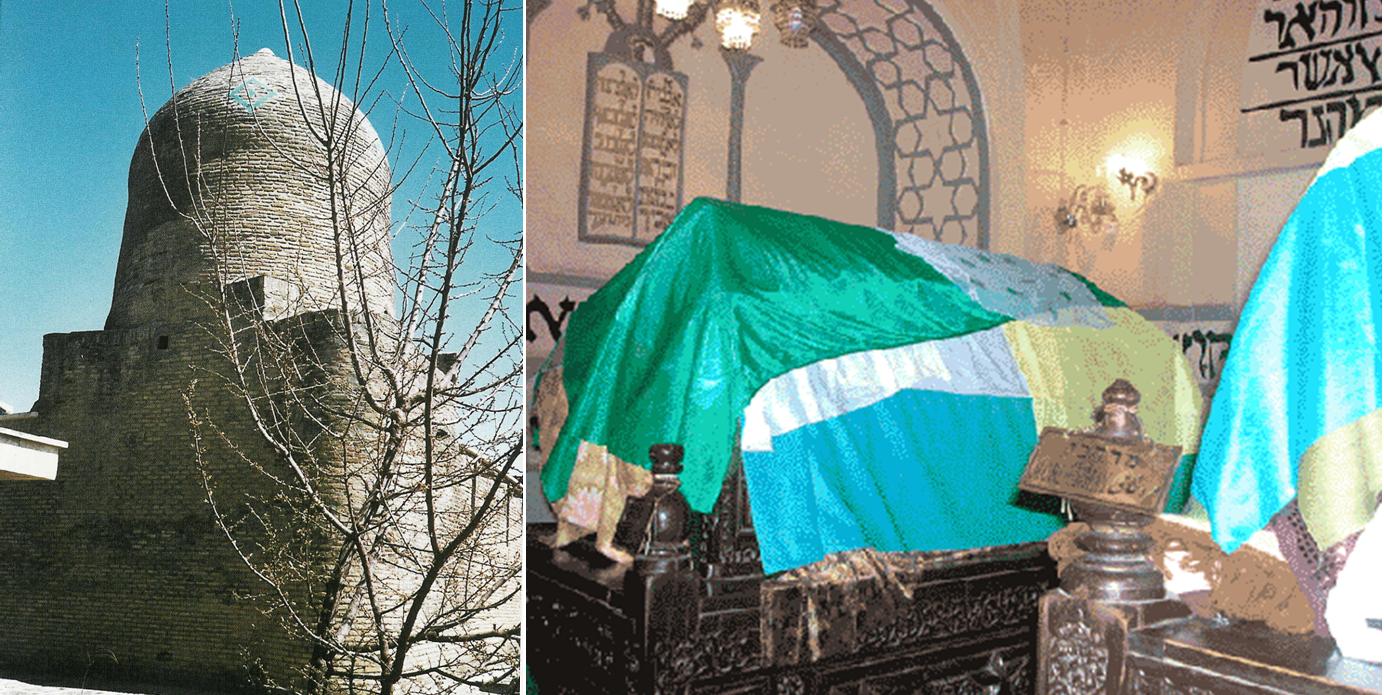

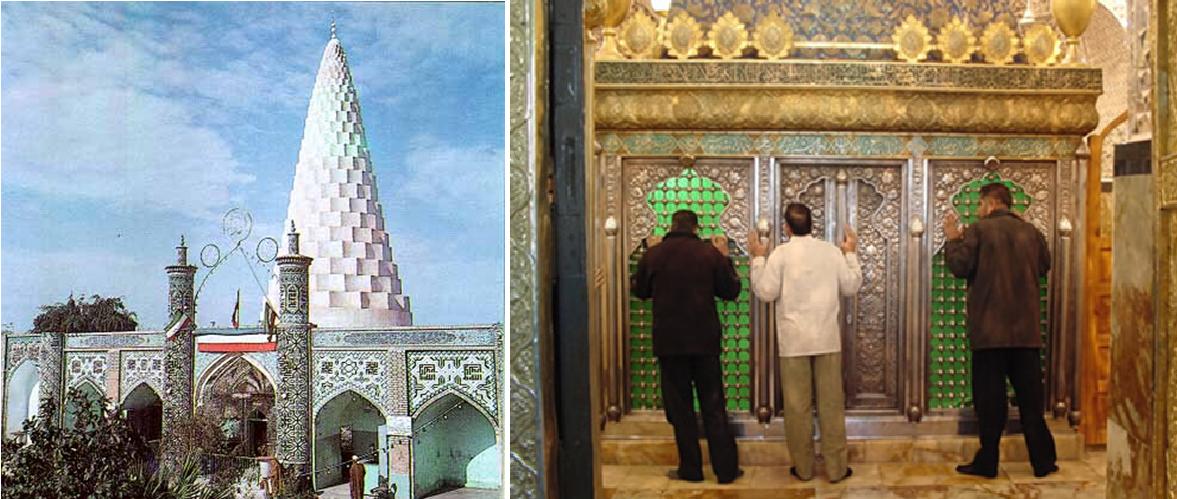

The tomb of Esther and Mordechai in Hamedan, northwest Iran. External view (left) and the interior of the tomb (right).

On 29 October 539 BCE, Cyrus II the Great (b. ca. 600 BCE, d. 530 BCE; q.v.) invaded Babylon, where he was welcomed as a liberator by the devotees of the chief deity of Babylon, Marduk. Likewise, many of the leaders of the Jews in Babylonia looked upon Cyrus as the person designated by God to fulfill Jeremiah’s prophecy (Jer. 29:14) that the Jews would be liberated and allowed to return to Judah. This attitude is reflected in the words of an unnamed prophet of the time, whose speeches are found in Isa. 40-66:

“Thus said the LORD to Cyrus, His anointed one / Whose right hand He has grasped, / Treading down nations before him, / Ungirding the loins of kings, / Opening doors before him / And letting no gate stay shut: / I will march before you / And level the hills that loom up; / I will shatter doors of bronze / And cut down iron bars. / I will give you treasures concealed in the dark / And secret hoards / So that you may know that it is I the LORD, / The God of Israel, who call you by name. / For the sake of My servant Jacob, / Israel My chosen one, / I call you by name, / I hail you by title, though you have not known Me. / I am the LORD and there is none else; / Beside Me there is no god. / I engird you, though you have not known Me, / So that they may know, from east to west, / That there is none but Me. / I am the LORD and there is none else” (Isa. 45:1-6 [This and all translations of biblical texts in this entry are taken from Tanakh, 1985]).

Rebuilding the Temple

Just as our unnamed prophet conceived of Cyrus as having been chosen by the One God, of whom he admits Cyrus had never heard, so did the Akkadian cuneiform inscription called the Cyrus cylinder (see also Cyrus the Great & The Cyrus Cylinder) picture Cyrus as chosen by Marduk:

“He [Marduk] scanned and looked (through) all the countries, searching for a righteous ruler willing to lead him (i.e., Marduk) (in the annual procession). (Then) he pronounced the name of Cyrus, king of Anshan, declared him to be(come) the ruler of all the world. Without any battle he made him enter his town Babylon, sparing Babylon any calamity. He delivered into his (i.e., Cyrus’s) hands Nabonidus, the king who did not worship him (i.e., Marduk). All the inhabitants of Babylon as well as of the entire country of Sumer and Akkad, princes and governors (included) bowed to him (Cyrus) and kissed his feet, jubilant that he (had received) the kingship, and with shining faces. Happily they greeted him as a master through whose help they had come (again) to life from death (and) had been spared damage and disaster, and they worshiped his (very) name” (Pritchard, 1969, pp. 315-16).

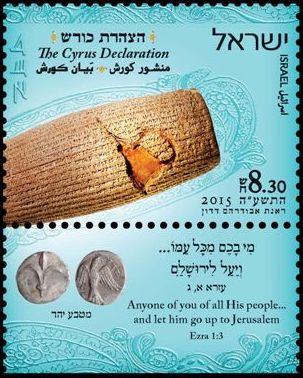

The Cyrus Cylinder housed at the British Museum (Picture Source: Angelina Perri Birney).

The unnamed Jewish prophet was not alone in his belief that Cyrus would restore the Jews to Jerusalem and enable them to rebuild Solomon’s Temple. Contemporary devotees of the Babylonian pantheon also believed that Cyrus was sent by their respective deities to rebuild the various temples that Cyrus’s predecessor in Babylon, King Nabonidus, a devotee of the moon god Sin, had desecrated (Pritchard, 1969, p. 314). In the light of Cyrus’s and his Achaemenid successors’ playing the role of the king of Babylonia in Babylon, the king of Elam in Susa, and that of Pharaoh in Egypt, it is possible to appreciate Cyrus’s portrayal as having been chosen by the God of Israel in the Edict of Cyrus recorded in a Hebrew version in Ezra 1:2-4 (see also 2 Ch. 36:23) and in an Aramaic version in Ezra 6:3-5. The Hebrew version reads as follows:

“Thus said King Cyrus of Persia: The LORD God of Heaven, has given me all the kingdoms of the earth and has charged me with building Him a house in Jerusalem, which is in Judah. Anyone of you of all His people—may his God be with him, and let him go up to Jerusalem that is in Judah and build the House of the LORD God of Israel, the God that is in Jerusalem; and all who stay behind, wherever he may be living, let the people of his place assist him with silver, gold, goods, and livestock, besides the freewill-offering to the House of God that is in Jerusalem” (Ezra 1:2-4).

With respect to the expression “God of Heaven,” E. Bickerman points out that the Achaemenid rulers used it to refer to all supreme divinities of the Semites (Bickerman, 1946, p. 257). Moreover, he notes that in speaking to Persians, the Jews at Elephantine called their deity ‘the God of Heaven’ (Bickerman, 1946, p. 257). Bickerman here alludes to the fact that among themselves they referred to their deity as YHW, a short form of the divine name YHWH (Porten, 1968, pp. 106-50). Bickerman suggests that Darius employed the appellation ‘God of Heaven’ because the Jewish authorities in Jerusalem officially designated their deity as “the God of Heaven and Earth” (Ezra 5:11), which they, in turn, derived from Deut. 4:39. It is quite plausible to go one step further and suggest that as early as the reign of Cyrus, the Jews from Egypt eastward designated their deity “the God of Heaven” and that consequently Cyrus adopted this epithet in his edict. The expression ‘the God of Heaven’ occurs seven times in Aramaic documents of the Achaemenid period quoted in the Hebrew Bible (Ezra 5:11, 12; 6:9, 10; 7:12, 21, 23) and twice in the Aramaic portions of the Book of Daniel (Dan. 2:18, 19). The Hebrew equivalent occurs four times in the memoirs of Nehemiah (Neh. 1:4, 5; 2:4, 20) and once in each of the two Hebrew versions of the Edict of Cyrus (Ezra 1:2; 2 Ch. 36:23).

The West Wall in Jerusalem. After his conquest of Babylon,Cyrus allowed the Jewish captives to return to Israel and rebuild the Hebrew temple. It is believed that approximately 40,000 did permanently return to Israel. President Truman in his support for the Jews in the twentieth century, evoked the name of Cyrus.

The purpose of the edict is to encourage the Jewish exiles and their descendants to leave Babylonia and to undertake the journey to Jerusalem and to participate in the building of the Temple. Cyrus suggests that those who are happy remaining in Babylonia might participate vicariously in this venture by contributing money and goods. In fact, Ezra 1:6 states that this is exactly what happened upon publication of the Edict of Cyrus. Therefore, H. L. Ginsberg argues most convincingly that the expression “and all who stay behind” (Heb. wkl hnshʾr) in the standard Hebrew text of Ezra 1:4 derives from a misguided attempt in antiquity to correct an obscure original wkl hnsʾ a hyper-literal rendition of an original Aramaic wkl dy ytl meaning “whoever will pick [him/herself] up” (Ginsberg, 1960, p. 169).

According to Ezra 2:64, 42,360 persons responded to the call to ascend to Jerusalem, not counting their male and female servants.

“All their neighbors [who may have preferred the comforts of Achaemenid Persia and Babylonia to the return journey] supported them with silver vessels, with gold, with goods, with livestock, and with precious objects, besides what had been given as a freewill offering” (Ezra 1:6; see the end of the edict quoted above).

Moreover, Ezra 1:7-11 reports that King Cyrus returned the Temple vessels, which King Nebuchadnezzar of Babylonia had carried away from Jerusalem in 586 BCE (see 2 Kgs. 25:13-17). The vessels were brought back to Jerusalem by Sheshbazzar, the prince of Judah. In fact, our unnamed prophet addressed the persons carrying the sacred vessels with the following words:

“Turn, turn away, touch naught unclean / As you depart from there; / Keep pure, as you go forth from there, / You who bear the vessels of the LORD!” (Isa. 52:11).

We saw that Cyrus sent a group of Jews under the leadership of Sheshbazzar to Jerusalem to build the Temple (Ezra 1:8, 11). According to a letter from Tattenai (Ezra 5:16), the governor of Trans-Euphrates, to Darius I the Great (r. 29 September 522-October 486 BCE; q.v.), the Jews claimed that Sheshbazzar had indeed laid the foundations of the Temple (Rainey, 1961, pp. 52-53). However, according to Ezra 3, it was Zerubbabel who laid those foundations in the second year after the arrival of the first group of Jews from Babylonia in Jerusalem.

Iranian Jews praying during Hanukkah celebrations on Tuesday, December 27, 2011 at the Yousefabad Synagogue, in Tehran, Iran (Source: Wodu).

In the second year of Darius I, the Prophet Haggai (Hag. 1:1-11) asserted that the Jews failed to build the Temple during the previous eighteen years because they were concerned only with their individual material success. Happily, according to Hag. 1:14, Zerubbabel son of Shealtiel, the governor of Judah, and Joshua son of Jehozadak, the high priest, responded to Haggai’s diatribe by setting to work immediately on the building of the Temple, which was dedicated in 515 BCE. The Book of Ezra-Nehemiah blames the failure to build the Temple during the eighteen years that followed the Edict of Cyrus on outside interference. However, the evidence presented by the Book of Ezra-Nehemiah (Ezra 4) for outside interference having been responsible for the failure to build the Temple during the reigns of Cyrus and Cambyses is totally unconvincing: the documents presented are dated to the reign of Artaxerxes, presumably Artaxerxes I (r. 465-24 BCE; q.v.), whose reign commenced half a century after the Temple had been rebuilt during the reign of Darius I. The full story remains to be reconstructed by historians when archeological research uncovers additional data.

Jews in law, government, and the military. Exactly as in other periods of Jewish history there were three parallel developments. Some Jews took advantage of the opportunity to return to their ancestral land; most chose not to do so; and many non-Jews adopted Judaism. Like the parents or grandparents of Mordechai and Esther who found their way to Susa, the children of many of the Jews who had been taken captive by the armies of King Nebuchadnezzar found their way to the far reaches of the Persian empire. At the time of Cyrus’s successor Cambyses II (r. 530-22; q.v.), that empire embraced territories from the Indus river in the east to Egypt and Ethiopia in the west (see Achaemenid Era). Many of these Jews found careers in the Achaemenid imperial army, as did several generations of Jews at Elephantine in Egypt in the fifth century BCE. Others, like the biblical Mordecai, Esther, and Nehemiah, found careers in government service. Given the extent of the Persian empire with its Persian language and Persian law, for the Achaemenid period Jewish history, virtually the world over, and the history of Iranian Jewry are synonymous. The Book of Esther takes for granted the idea that the fortunes of all Jews almost everywhere was determined by the decisions of the Persian kings in their several seats of government at Susa, Ecbatana (modern Hamadan; q.v.), Persepolis, and Pasargadae.

The Cyrus Declaration Stamp Sheet (Source: Israel Post).

Historians long assumed that during the seventy years from the dedication of the Temple (515 BCE) until the arrival of Nehemiah (445 BCE) Judah was attached to the province of Samaria. This assumption would account for the antagonism of Sanballat, the Persian governor of Samaria, from whose territory, as it were, Judah was detached and given to Nehemiah. That very same assumption would also account for the absence of biblical testimony to any Achaemenid-period governors of Judah other than Sheshbazzar, Zerubbabel, and Nehemiah. Archeological discoveries of the last half century have altered this false impression. Relevant archeological data include the seal of Elnathan, the governor of Judah (sixth century BCE), a clay seal impression with his name as well as the personal seal of Shelomith, who designated herself as Elnathan’s ʾamah, a Hebrew term that may mean “royal official” (Avigad, 1976, pp. 31-32; Avigad, 1997, p. 31; Meyers, 1985, pp. 33-38). From seal impressions on clay jars dated to the early fifth century BCE recovered from Ramat Rahel, we know of two more governors of Judah, Jehoezer and Ahzai, whose terms of office should be dated midway between Zerubbabel and Nehemiah (Avigad, 1976, pp. 6, 35).

According to Ezra 7:12-14, King Artaxerxes, presumably Artaxerxes I, appointed Ezra the priest and expert in the law of the God of Heaven “to regulate Judah and Jerusalem according to the law of your God, which is in your care” (Ezra 7:14). Ezra’s role in promulgation of the Torah (understood to be law: Aramaic dat derived from Old Persian dāta) by royal decree was consistent with Achaemenid policy. Just as Artaxerxes authorized the promulgation by Ezra of the law(s) of the God of Heaven, i.e., the Torah, among the devotees of God throughout Trans-Euphrates, so did Darius I in 518 BCE command Aryandes (q.v.), the satrap of Egypt, to assemble experts to codify the Egyptian laws. The Egyptian code, inscribed in both Aramaic and Demotic on a papyrus roll, was published in 495 BCE (Porten, 1968, p. 22). Likewise, the expression “the law of the king” alongside that of “the law of your God” in Ezra 7:26 (and see also Ezra 8:36; Esth. 3:8) refers to the fact that Darius drafted a new Persian legal code for the empire alongside the codified laws of the numerous peoples over whom he ruled (Frye, 1962, p. 119).

Iranian Jews in a Synagogue in Tehran in the Fall of 2016 (Source:AIC).

Nehemiah had been cupbearer to King Artaxerxes (presumably Artaxerxes I) when he was appointed governor of Judah (Neh. 2:1). As cupbearer, Nehemiah would have been the royal official closest to the king. He would have been able to determine who got to speak to the king. The king’s very life thus depended on Nehemiah, given that almost half of the Achaemenid kings were assassinated. Nehemiah would have been well trained in court etiquette, and he was likely of handsome appearance. It was he who chose the wines to be placed before the king. Day after day Nehemiah would risk his own life by skimming off wine from the king’s cup and swallowing it to make certain that it contained no deadly poison (Yamauchi, 1990, pp. 258-60). Nehemiah’s term as governor began in 445 BCE, and ended ca. 433 BCE (see Neh. 2:1 and 13:6; Weinberg, 1992, pp. 127-38). Like pre-exilic Israelite and Judean prophets, Nehemiah contended with socio-economic inequities (Neh. 5) and violation of the Sabbath (Neh. 10:32). Nehemiah persuaded the affluent to renounce for the sake of the common good claims against the impoverished to significant material assets (Neh. 5:13). Nehemiah’s additional title tirshatha (Ezra 2:63; Neh. 7:65, 69; 8:9; 10:2) is probably derived from Old Persian tarsa, and it probably means “the one to be feared.”

Gustave Dore’s painting of Cyrus the Great restoring the sacred vessels of the temple to the Jews (Posted in the KingFoska Files website). When Cyrus conquered Babylon, he ordered the sacred religious objects of the Jerusalem Temple to be restored to their rightful owners, the Jews. For more see here …

After Nehemiah, the next governor of Judah known to us bore the characteristically Persian name Bagohi. The precise derivation of this name is uncertain. Pliny suggests that it is not a proper name but a title meaning eunuch (Pliny, Natural History 13.41 cited by White, p. 567) It was Governor Bagohi to whom Jedoniah, the high priest, and his colleagues from Elephantine appealed in their papyrus letter in Aramaic dated 20 Marheshvan in the seventeenth year of Darius II (r. 423-04 BCE; q.v.)—i.e., 408 BCE—for help in rebuilding their sacrificial Temple of YHW (Pritchard, 1969, p. 492; Cowley, 1923, no. 31; Porten, 1968, pp. 284-95 and passim). The Jews of Elephantine explained that on 14 Tammuz 410 BCE, while the satrap Arsames was away from his palace in Memphis on a mission to King Darius, the priests of the Egyptian god Khnum bribed the Persian commander of the Elephantine garrison, Vidranga, to let them destroy the Jewish temple (Cowley, 1923, no. 30). Troops commanded by Vidranga’s son Nefayan demolished the temple. The letter of 20 Marheshvan indicates that a previous letter to Johanan the Jewish high priest at Jerusalem had gone unanswered. In addition, Jedoniah informs Bagohi that he is issuing the same request to Delaiah and Shelemiah the sons of Sanballat, the governor of Samaria. Among the Elephantine papyri is a memorandum that shows that Bagohi and Delaiah jointly replied, calling upon Arsames “to rebuild it [the temple] on its site as it was before, and the meal offering and the incense to be made on that altar as it should be” (Cowley, 1923, no. 32; Pritchard, 1969, p. 492). This joint reply supports the contention of many modern historians that the schism which separates Samaritans from Jews had not yet developed in the fifth century BCE. Moreover, their joint support for the rebuilding of the Jewish sacrificial temple at Elephantine suggests that these two leaders at least did not hold that the divine law (Deut. 12) actually prohibited the worship of God by sacrifice in temples other than the one the Jews had built at Jerusalem and the one the Samaritans would build on Mount Gerizim. To this day it is commonplace in both Orthodox and non-Orthodox Judaism for accepted practices to run counter to what is prescribed and/or proscribed in sacred canonical texts. When religious leaders and devoted laypersons are questioned as to how that is possible, they usually respond, “We do not go by that particular text.” Presumably that is what the Elephantine Jews would have said if someone had called into question their having a Temple outside of Jerusalem in apparent violation of Deuteronomy 12.

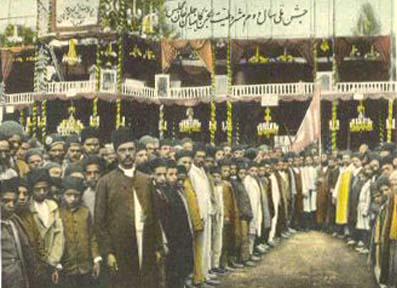

Portrait of Iranian Jews in the city of Hamedan in 1918 (Source: Public Domain and originally from National Library of Iran).

Beginnings of a Persian Judaism in Antiquity

Throughout the Achaemenid empire, individuals and groups of devotees of YHW(H) can be recognized as such because of their overwhelming tendency to give their children names that contain the name of their deity. Typical are the names of Sanballat I’s sons, Delaiah and Shelemiah. Nevertheless, some devotees of YHW(H) bore names of Assyro-Babylonian origin such as Mordecai, which is derived from the Assyro-Babylonian god Marduk; Esther, which is derived from the name of the Assyro-Babylonian goddess of love, war, and the planet Venus, namely, Ishtar; and Sanballat, which is a shortened form of Assyro-Babylonian Sin-uballit, which means “The moon god gave(him) life.” Many persons whose activities indicate that they were adherents of YHW(H) bore Iranian names. One of the most common of these Iranian names is Bagohi (see, in addition to the governor of Judah mentioned in the Elephantine papyri, Ezra 2:2, 14; 8:14; Neh. 7:7, 19; 10:17).

The era of tolerance for all ethnic and religious groups inaugurated by Cyrus may have been a catalyst for the universalism preached by the very same anonymous prophet who heralded Cyrus’s liberation of Babylon as the harbinger of the redemption of Jews from exile:

“As for the foreigners / Who attach themselves to the LORD, / To minister to Him / And to love the name of the LORD, / To be His servants / All who keep the sabbath and do not profane it, / And who hold fast to My covenant / I will bring them to My sacred mount / And let them rejoice in My house of prayer. / Their burnt offerings and sacrifices / Shall be welcome on My altar; / For My House shall be called / A house of prayer for all peoples” (Isa. 56:6-7).

This prophet’s summoning Gentiles to become “attached to the Jewish people” by observing the Sabbath and holding fast to God’s covenant accounts for several developments reflected both in biblical writings from the Achaemenid era and in data recovered by archeology. The Book of Esther, which is the most characteristically Iranian book of the Bible in both its setting and its language, takes it for granted that wherever there are Jewish communities there will also be “those who attach themselves to them” (Esth. 9:27). In later times this term for “Jews by choice” will be replaced by the term gerim (proselytes).

The above photo taken on November 20, 2014, was featured in an article by Ishaan Tharoor in the Washington Post entitled “Iran unveils a memorial honoring Jewish heroes” (December 18, 2014). As noted by Ishaan Tharoor, the above shows an Iranian Jewish man holding a Torah scroll at the Molla Agha Baba Synagogue, in the city of Yazd 420 miles (676 kilometers) south of capital Tehran, Iran (Photo:Washington Post & Ebrahim Noroozi/AP).

Achaemenid period Aramaic papyri from Egypt, the Murashu and Sons Banking House archives on clay tablets in Babylonian cuneiform from Nippur in southern Iraq, and an Aramaic inscription on a sarcophagus found at Aswan in Egypt all testify to many people bearing the name Shabbetai, which reflects the importance of the Jewish Sabbath (cf. Isa. 56:6 quoted above; Coogan, 1976, pp. 123-24; Porten, 1968, pp. 124-27). Porten shows that not all persons named Shabbetai were Jews (Porten, 1968, p. 127). It is seldom realized that both the Sabbath and the seven-day week were Israelite innovations of great antiquity (Gruber, 1969, pp. 19-20). It stands to reason that Gentiles were attracted to the Jewish Sabbath because this social institution made leisure, which previously had been the rare privilege of royalty and nobility, a matter of routine even for slaves. In modern times in Israel on the seventh day Sabbath and on Sunday (often referred to as the Sabbath by many Protestants) in countries with a large Protestant population it is common to see a virtual cessation of industrial production and commerce. This cessation of production and commerce enables masses of working people to enjoy leisure. In many countries in the Far East, where the influence of the Hebrew Bible is negligible, one can observe that construction of buildings and virtually all industrial and commercial activities continue on Sunday as on any other day of the week. There is no indigenous tradition of having a day off once a week. That is how life was everywhere before the Jews, carried away to what became the Persian empire, brought the Sabbath and its promise of social and economic equality to a world beyond the two banks of the Jordan river.

Universalism: A Characteristic of Achaemenid-period Jewish Literature

Just as the anonymous prophet, the so-called Second Isaiah, whose writings are appended to the Book of Isaiah speaks of the Temple to be built on Mount Moriah in Jerusalem as “a house of prayer for all peoples,” so does Zechariah, who spoke in the name of the God of Israel at the beginning of the reign of Darius I tell us of the role of the Jews in bringing the knowledge of God to the world at large:

“Thus said the LORD of Hosts: Peoples and the inhabitants of many cities shall yet come—the inhabitants of the one shall go to the other and say, ‘Let us go and entreat the favor of the LORD, let us seek the LORD of Hosts; I will go too.’ The many peoples and multitude of nations shall come to seek the LORD of Hosts in Jerusalem and to entreat the favor of the LORD. Thus said the LORD of Hosts: In those days, ten men from nations of every tongue will take hold—they will take hold of every Jew by a corner of his cloak and say, ‘Let us go with you, for we have heard that God is with you’” (Zech. 8:22-23).

Iranian Jewish community members in Tehran congregate in 1920 to celebrate the anniversary of the Iranian Constitutional Revolution (Source: Public Domain).

The call to universalistic love and compassion is found also in the following passage in a later chapter of the same prophetic Book of Zechariah:

“In that day I will all but annihilate all the nations that came up against Jerusalem. But I will fill the House of David and the inhabitants of Jerusalem with a spirit of pity and compassion, and they shall lament to Me about those who are slain, wailing over them as over a favorite son and showing bitter grief as over a first-born” (Zech. 12:9-10).

The universal vision of the Book of Zechariah is epitomized with the following prediction, with which for the last several centuries virtually every Jewish worship service concludes:

“And the LORD shall be king over all the earth; in that day there shall be one LORD with one name” (Zech. 14:9).

So successful apparently were the anonymous prophet of Isa. 40-66 in the reign of Cyrus and Zechariah in the reign of Darius I in spreading knowledge of the One God that the biblical Prophet Malachi, traditionally regarded as the last of the Old Testament Prophets, tells us that in his time God could declare:

“For from place where the sun rises to the place where it sets, My name is honored among the nations, and everywhere incense and pure oblation are offered to My name; for My name is honored among the nations—said the LORD of Hosts” (Mal. 1:11).

Biblical commentators, historians, and archeologists have yet to identify the non-Jewish devotees of God throughout the length and breadth of the Achaemenid state, to whom this prophet refers.

The universalism that we saw reflected in the Achaemenid-period writings found in the latter part of the Book of Isaiah and in the biblical books of Zechariah and Malachi is reflected also in the Book of Ezra, which relates that, when the Jews who returned to the Land of Israel in accord with the Edict of Cyrus celebrated the festival of Passover on the fourteenth day of the first month (later called Nisan, which corresponds more or less to Eastertide in western Christendom), they were joined in their festival celebration by “all who joined them in separating themselves from the uncleanness of the nations of the lands to worship the LORD God of Israel” (Ezra 6:21). Here, as in the passages in Isaiah and in Esther cited above, mention is made of born Jews’ accepting into their fold Jews by choice, which is to say, persons who were not born Jewish but who adopted the Jewish religion. In the same vein, Ezra 2:59 and Nehemiah 7:61 refer rather casually to the people from Tel-melah, Tel-harshah, Cherub, Addon, and Immer who could not testify to their Israelite ancestry, but who were nevertheless accepted as part and parcel of the Jewish people who came from Babylonia to Judah under the sponsorship of King Cyrus.

Iranian Jewish Es’hagh Akhamzadeh locks the door housing the Torah scroll after placing it in inside the designated cupboard during morning prayers at Youssef Abad synagogue in Tehran on Sept. 30, 2013 (Source: Photo by Behrouz Mehri & Resse Elrich’s article “Right-wing American bloggers have a problem with facts about Iran’s Jews” in Agence France-Presse, August 24, 2015).

The very same universalism is reflected in one of the shortest books of the Bible, the Book of Jonah, commonly dated to the Achaemenid period because of its language and its referring to the LORD as “the God of Heaven,” just as he is referred to in the Edict of Cyrus. In the Book of Jonah, the prophet is sent to call the people of Nineveh to repent of their erstwhile, unspecified sins lest their city be destroyed. Even the animals put on sackcloth and fast, and the entire population repents. God rescinds his conditional decree of destruction. Jonah is thus the most successful prophet in the annals of biblical literature. This prophet, who has long been diagnosed as suffering from chronic depression, has one of his bouts of depression just at the height of his prophetic career. His pathological condition is born out by his excessive grief over the death of a plant, which had previously made Jonah happy. God, in the book’s conclusion, uses Jonah’s pathological grief over the plant as an occasion to bring home the lesson of God’s concern for the people and the livestock of Nineveh, whom God had been able to save from destruction because they heeded the call of the prophet. The meta-message is that God’s concern extends to all living creatures, perhaps not to the plant that had shielded Jonah from the sun, and is not limited to the Jews.

In the context of Achaemenid-period Judaism’s overwhelming universalism represented by Isa. 40-66; Zech.; Mal.; Jonah; and, according to most modern authorities, Joel, Job, Ruth, and parts of the Book of Proverbs as well, the account of Nehemiah’s and Ezra’s respective diatribes against marriage of Jewish men to women from among “the peoples of the land(s)” are totally anomalous. Ezra’s diatribe is found in Ezra 9-10, while Nehemiah’s two diatribes are found in Neh. 13. It is widely repeated in modern biblical scholarship that these diatribes reflect a dominant xenophobic tendency in Second Temple Judaism, which was the antithesis of the universalism preached by the Apostle Paul. Yehezkel Kaufmann (Kaufmann 1964, pp. 296-97) argued that the diatribes of Ezra and Nehemiah derived from their not having had at their disposal the option of religious conversion. Ginsberg (Ginsberg 1982, pp. 7-18), on the other hand, argued that the compiler of the Book of Ezra-Nehemiah was motivated by his commitment to uphold the texts in Deuteronomy 7 and 23 that specifically prohibited Jews from intermarrying with the peoples of the seven aboriginal nations of the land of Canaan and with Moabites and Ammonites. Yonina Dor (Dor, 2006) presents an elaborate and highly complicated theory, which attempts to reconcile the account of the expulsion of the foreign women with the various statements in Ezra-Nehemiah that refer to the acceptance of persons of non-Israelite origin as part of the Jewish body politic. A careful reading of the book of Nehemiah reveals that, in fact, persons—including Nehemiah—who signed an agreement not to give their daughters in marriage to the peoples of the land or take their daughters for their sons (Neh. 10:31) were the same Jewish people we met at the Passover celebration in Ezra 6:21, namely:

“the rest of the people, the priests, the Le-vites . . . and all who separated themselves from the peoples of the lands to [follow] the Teaching of God, their wives, sons and daughters” (Neh. 10:29).

When History goes beyond Politics: Koresh or Cyrus street in Jerusalem. There is currently no street named Cyrus or Koroush in Tehran, the capital of Iran today. There is also an “Iran” street in Israel.

So it turns out that the agreement that Nehemiah got everyone to adhere to and which obligated persons not to marry persons who worshipped deities other than the LORD also took for granted, as did Isaiah 56 and Esth. 9:27, that the Jewish people included persons who separated themselves from the idolatrous populations and joined themselves to Israel as Jews by choice. Consequently, it turns out that the dichotomy between the universalism of Isa. 56 and the alleged xenophobia of Ezra and Nehemiah is not reflected in the biblical text, which places Ezra’s and Nehemiah’s pronouncements in the context of the aforementioned signed agreement to which Nehemiah is himself a signatory. It follows that the universalism preached in Isaiah 40-66 and in Zechariah is upheld also by the Book of Ezra-Nehemiah, when the latter composition is not read selectively in order to prove that the Jews invented xenophobia.

The Elephantine Papyri and Women’s Rights

The numerous Aramaic documents from Elephantine (q.v.) on leather, papyrus, and ostraca (potsherds) are the most important sources of information concerning Judaism in the Achaemenid empire. The earliest of these documents is dated 495 BCE, while the latest bears the date of 399 BCE. A very small number of these documents refer to the Jewish Temple and to the observance of Passover. However, most of these documents are contracts pertaining to marriage, divorce, and inheritance. An especially famous feature of the Elephantine papyri is the provision in marriage contracts guaranteeing both spouses the right to initiate a divorce. This provision has been of special interest in modern forms of Judaism, which have sought means of getting around the requirement in halakhah (specifically Mishnah Yebamot 14:1), according to which only the husband can initiate a divorce proceeding. There is a growing scholarly consensus that the Elephantine Jewish wife’s right to initiate a divorce has its roots in ancient Western Asia and even in Hebrew Scripture (Gruber, 1999, pp. 161-64). Those who make this claim are motivated, at least in part, by the desire to show that a non-patriarchal conception of marriage, whether in modern or ancient times, is a return to the pristine glory of Judaism rather than a symptom of assimilation to Gentile ways. It should be noted in this context that what Jews refer to as assimilation is the functional equivalent of colonialism in the larger world of Asia and Africa. Contrary to modern Western presuppositions, no time or place seems to have a monopoly on either sexism or equality of the sexes. A very important part of the legacy of Achaemenid period Jewry, which has been rediscovered by modern experts in the dynamics of Jewish law, is the provision for women to be able to initiate a divorce.

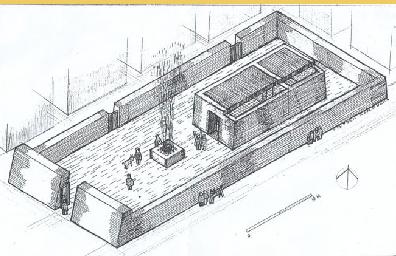

A reconstruction of the Jewish Temple in Elephantine in Egypt. The Achaemenids subsidized the repair and reconstruction of Jewish temples as a matter of state policy. For more see here …

Probably the last governor of Judah during the Achaemenid era was Hezekiah, known only from fourth century BCE silver coins bearing the typical, for that time, picture of an owl and the inscription “Hezekiah the governor” (Rahmani, 1971, pp. 158-60). According to Avigad the date would be ca. 330 BCE (Avigad, 1976, p. 35). This date makes Hezekiah a contemporary of Sanballat III. The latter was the Samarian governor in the reigns of Darius III (r. 336-31 BCE; q.v.) and Alexander the Great (356-23 BCE; q.v.).

Five of the most important figures in late biblical books—Ezra, Nehemiah, Mordecai, Esther, and Daniel—belong to the almost unknown history of Persian Jewry in the Achaemenid period.

The tomb of Daniel in Khuzestan in southwest Iran. The main structure (note cone-like dome) as it stands today (left) and Iranian pilgrims paying homage within the tomb of Daniel.

But with the exception of a few seals and seal impressions from Judah and the biblical narratives of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther, almost all we know of Jews and Judaism in this obscure period, when Jewish history and the history of Persian Jewry were one, is what we have learned from the Elephantine papyri, which tell us about a community of Jewish soldiers loyally serving the Persian king from their homes on an island in the Nile River. Undoubtedly, new archeological discoveries will shed additional light on the early history of Achaemenid Persia and its Jews who, having been liberated from the Babylonian yoke by Cyrus, chose, like Queen Esther herself, in a manner so characteristic of Jews everywhere, to remain in Persia and to build their lives there rather than join in the rebuilding of Jerusalem (on the reputed tomb and coffer of Esther in Hamadān, see Figure 3 and Figure 4).

Bibliography

Nahman Avigad, Bullae and Seals from a Post-Exilic Judean Archive, Qedem: Monographs of the Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jersualem, 4, Jerusalem, 1976.

Idem, Corpus of West Semitic Stamp Seals, rev. and comp. Benjamin Sass, Jerusalem, 1997.

Elias Bickerman, “The Edict of Cyrus in Ezra 1,” Journal of Biblical Literature 65, 1946, pp. 249-75.

Michael David Coogan, West Semitic Personal Names in the Murashu Documents, Harvard Semitic Monographs 7, 1976.

A. Cowley, Aramaic Papyri of the Fifth Century B.C., Oxford, 1923.

Yonina Dor, Have the “Foreign Women” Really Been Expelled? Separation and Exclusion in the Restoration Period, 2006 (in Hebrew). R. N. Frye, The Heritage of Persia, London, 1962.

Harold Louis Ginsberg, “Critical Notes: Ezra 1:4,” Journal of Biblical Literature 79, 1960, pp. 167-69.

Idem, The Israelian Heritage of Judaism, New York, 1982.

Mayer I. Gruber, “The Source of the Biblical Sabbath,” Journal of the Ancient Near Eastern Society of Columbia University 1/2, 1969, pp. 14-20; repr. Mayer I. Gruber, The Motherhood of God and Other Studies, Atlanta, 1992.

Idem, “The Status of Women in Ancient Judaism,” in Judaism in Late Antiquity. Part Three: Where We Stand: Issues and Debates in Ancient Judaism II, Jacob Neusner and Alan J. Avery-Peck, eds., Leiden, 1999, pp. 155-76.

Yehezekel Kaufmann, History of the Israelite Religion VIII, 1964 (in Hebrew). Eric M. Meyers, “The Shelomith Seal and the Judean Restoration, Some Additional Considerations,” Eretz Israel 18, 1985, pp. 33-38.

Bezalel Porten, Archives from Elephantine: The Life of an Ancient Jewish Military Colony, Berkeley, 1968.

James B. Pritchard, Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament, 3d ed., Princeton, 1969.

L. Y. Rahmani, “Silver Coins of the Fourth Century B.C. from Tel Gamma,” Israel Exploration Journal 21, 1971, pp. 158-60.

Anson F. Rainey, “The Satrapy ‘Beyond the River,” Australian Journal of Biblical Archaeology 1, 1961, pp. 51-78.

Houman Sarshar, ed., Esther’s Children: A Portrait of Iranian Jews, Los Angeles, 2002.

Tanakh: A New Translation of the Holy Scripture, Philadelphia, 1985.

Joel Weinberg, The Citizen-Temple Community, tr. Daniel L. Smith-Christopher, Sheffield, UK, 1992.

Sidnie Ann White, “Bagoas,” in Anchor Bible Dictionary, New Haven, 1992.

D. J. Wiseman, Chronicles of Chaldean Kings (626-556 B.C.) in the British Museum, London, 1961.

Edwin M. Yamauchi, Persia and the Bible, Grand Rapids, 1990.