The article “How nations mix ingredients in their food based on traditional Persian medicine” below was written in 2012 by Fariba Karimi, a Post-Doctoral researcher at the Department of Computational Social Science at GESIS-Leibniz-Institute for the Social Sciences. Kindly note that the version of the article printed below contains images not displayed in the original version. Six of the graphs in the original article have also been reformatted.

=============================================================================

January 2010, I was in Berlin with a good Turkish friend. She is vegetarian. At some point she expressed her stomachache. I turned to her and said “of course you have stomach ache because you ate this and that together”. She looked at me strange that what I am talking about!

That was a shock to me. The ingredients mixing knowledge that back in Iran sounds completely obvious to everyone, is not that obvious even in Turkey! I started explaining her the rules on how to combine foods and my friend was amazed. Then after, I tried to observe how other nations combine food and how the knowledge of food mixing is widespread.

In 2011 I met Yong Yeol Ahn in a conference. He was researching on the networks of food pairing in various cuisines. Gratefully, he shared the dataset of recipes with me. Gradually, as a small side project, I started looking at some aspects of that data.

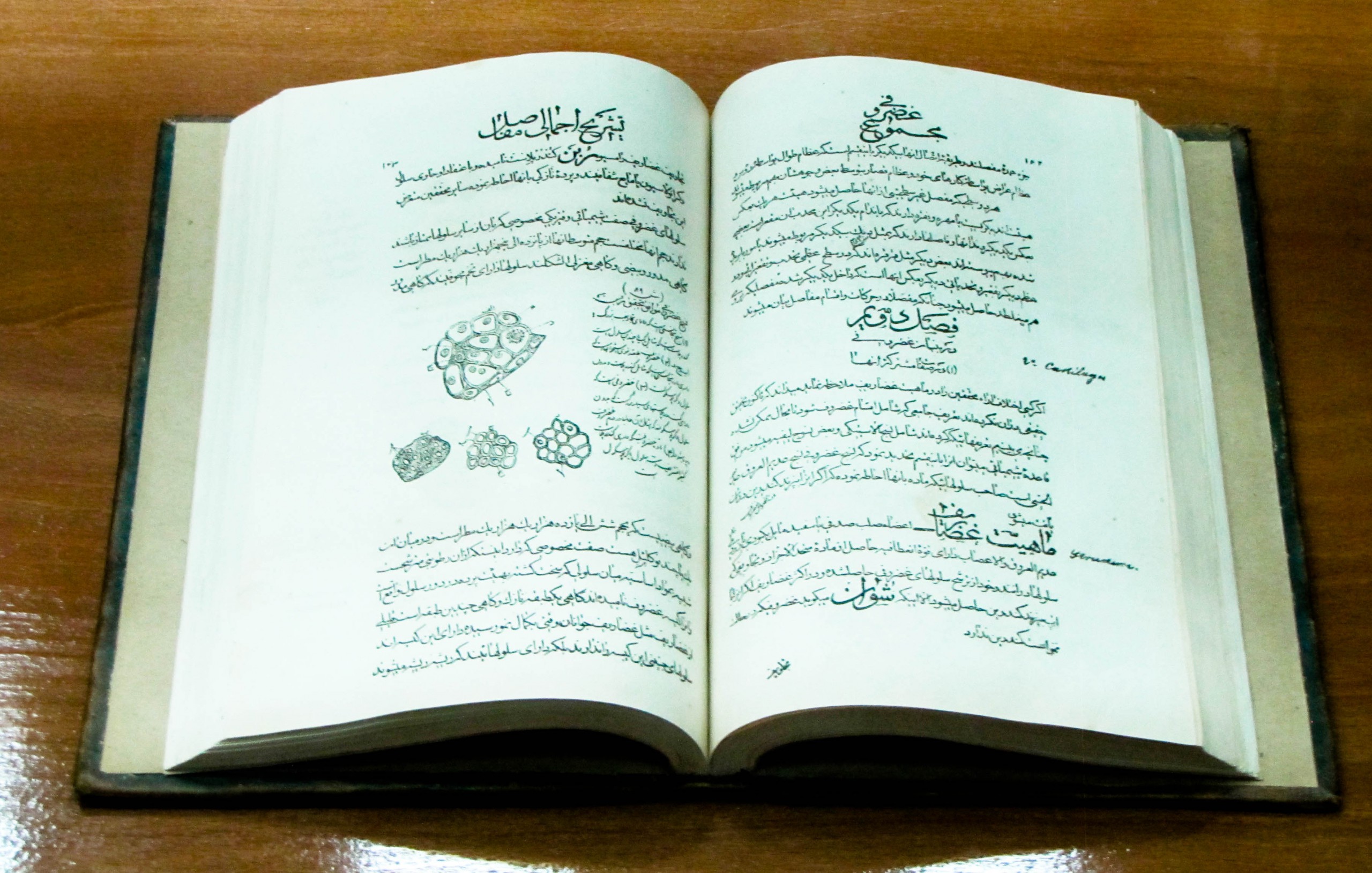

Let me first start with sharing with you a background of the tradition knowledge of ingredient mixing. Traditional Persian medicine developed by Avicenna (981-1037). Avicenna in his well-known book, The canon of Medicine, integrated and studied the principle of various medicine such as Greeks, Europeans, East Indians, Persians, Arabs, Chinese and Tibetans. In this book, he aggregated variety of methods and makes them into one standard principle of medicine.

Avicenna methodology is based on the ancient theory of four temperaments, known as Unani medicine (Tibb). In the Unani medicine there is not a single cause for disease, rather a result of disorder in the body metabolism.

A portrait of Avicenna on a silver vase housed at the Museum and Mausoleum of Abu-Ali Sina (known as Avicenna in the West) in Hamadan, northwest Iran (Source: Adam Jones in Public Domain). Ibn Sina was a Persian physician as well as philosopher (see for example – Finger, 2001, p. 177; Finger, S. (2001). Origins of Neuroscience: A History of Explorations Into Brain Function. Oxford University Press).

Unani Tibb, a humoral medical system, presents causes, explanations and treatments of disease based on the balance or imbalance of the four humors (akhlaat) in the body: blood (khun), mucus (bulghum), yellow bile (safra), and blackbile (sauda). These combine with four basic qualities (quwaat): heat (garmi), cold (sardi), moisture (rutubaat) and dryness (yabis). Dominance of one of the humors in the body gives each person his or her individual temperament (mizaj) : sanguine (dumwi), phlegmatic (balghumi), choleric (safravi), and melancholic (saudawi).

For Avicenna and his contemporary followers, there is no such thing as a ‘single’ cause of disease; rather an outcome of various factors, such as the food and body metabolism. Avicenna believed most illnesses arise solely from long-continued errors of diet and regimen.

Based on Unani system, foods are said to be either ‘hot’ (garmi) or ‘cool’ (sardi). This classification is consistent with other systems that seek to obtain an overview of the metabolic process, such as the East Indian Ayurvedic medicine and traditionsl chinese medicine.

In this post, I do not intend to discuss how this medicine developed and spread out over the world. Rather, I want to take a look on how other nations mix their food ingredients based on traditional Persian food culture.

A bowl of Ash-e Anar known for its unique taste made with pomegranates (Picture Source: Public Domain).

Persian cuisines adapted the Unani system in the way of combining different ingredients. In Persian culture, foods are categorized into two big categories, hot and cold. As a rule of thumb, basic components of a food are metabolically hot. Cool ingredients are added seasonally such that the whole cuisine has good hot-cold balance.

Foods that are sardi, or cold, place several burdens on the body. They are harder to digest. They are harder to assimilate (absorption of micro-nutrients into the blood stream and cells; moreover consequently, they leave a greater residue of superfluous waste products.

Here is the hot-cold list of ingredients that I collected from different Iranian sources. I tried to keep it reliable but also considering crowd wisdom. Therefore it might not be completely accurate. When I was browsing through different Iranian websites, I noticed some of categorizations are contradictory. I tried to check more than two or three sources to make sure that the categorization is reliable.

Hot (garmi) ingredient list:

scallion, pea, roasted pea, soybean, radish, sesame oil, nutmeg, walnut peanut, peanut butter, fenugreek, caraway, cayenne, basil, vanilla, parsley, bell pepper, green bell pepper, chickpea, leek, broccoli, peanut, berry, carrot, ginger, red bean, nutshell, coconut, kakao, cabbage, honey, dates, sesame, mango, morus, banana, peach, orange, eggplant, potato, mushroom, shiitake, savory, mint, saffron, pepper, grape, green bean, pistachio, wheat, pasta, noodle, bread, egg, cumin, almond, coconut, hazelnut, celery, shrimp, camel meat, liver, butter, lamb, chicken broth, bird, chickpea, cilantro, cinnamon, raisin, lobster, sesame seed, cayenne, marjoram, oat, tarragon, thyme, cauliflower, fennel, oregano, lavage, nutmeg.

The diversity of Persian cuisine as displayed in the Ariana restaurant in London, England (Picture Source: Ariana Restaurant).

Cold (sardi) ingredient list:

citrus, oyster, cheese, Jerusalem artichoke, bitter orange, snap bean, green bean, cod, cilantro, starch, pork, tomato, vinegar, coriander, genus, watermelon, cucumber, pumpkin, Pomegranate, cheese, watermelon, pear, apricot, okra, spinach, corn, grain, rhubarb, squash, lime, lettuce, rice, lentil, strawberry, dill, coriander, yogurt, milk, fish, veal, apricot, rabbit, goat, beef broth, roasted beef, margarine, butter milk, celery, sprouts, zucchini, spinach, cabbage, okra, cauliflower, broccoli, white potato, sweet potato, carrot, cucumber, soybean, turnip pea, lima beans, kidney_bean, coconut, brown_rice, cilantro, rheum tuna, salmon, veal, bacon, crab, pork sausage, catfish, tamarind, mussel.

A copy of the Persian manuscript of Ibn Sina’s (Avicenna’s) “Canon of Medicine” housed at the Museum and Mausoleum of Abu-Ali Sina (known as Avicenna in the West) in Hamadan, northwest Iran (Source: Coffeetalk in Public Domain).

I used the data from this study to check ingredient combinations in different geographical regions. Here is a sample of how the data looks like:

North America: green bell pepper, wheat, meat, onion, chicken_broth, cayenne, scallion, celery, smoked sausage, bell pepper

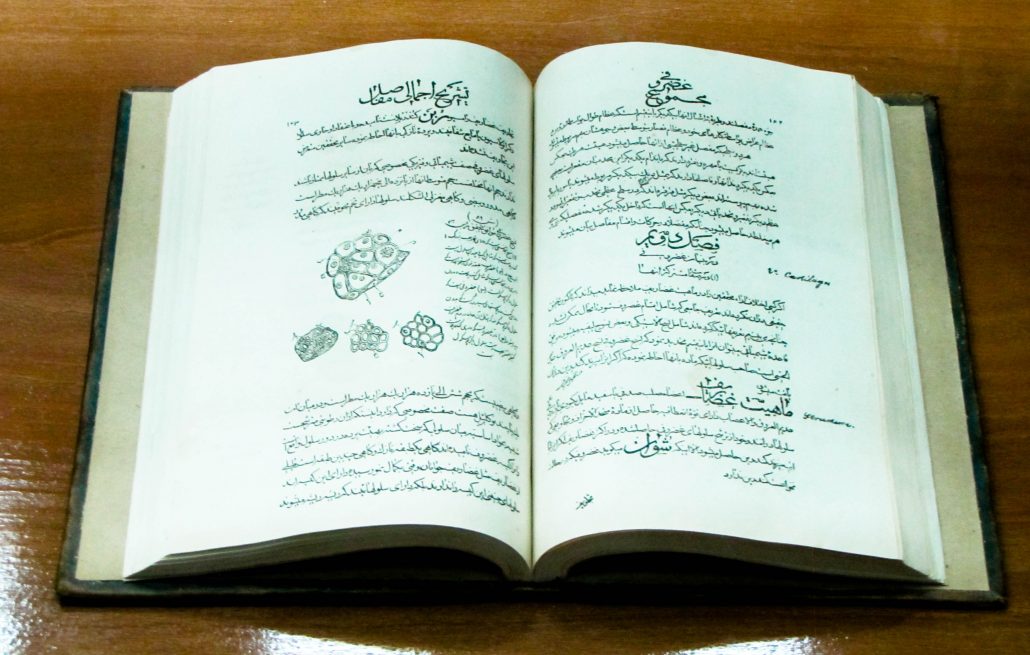

For various geographical regions I plotted number of hot and cold ingredients per recipes. Each dot in the plots is one recipe. The darker the blue, shows more recipes are lying there.

Graph-Figures of various geographical regions with respect to hot/cold ingredients as displayed by Fariba Karimi.

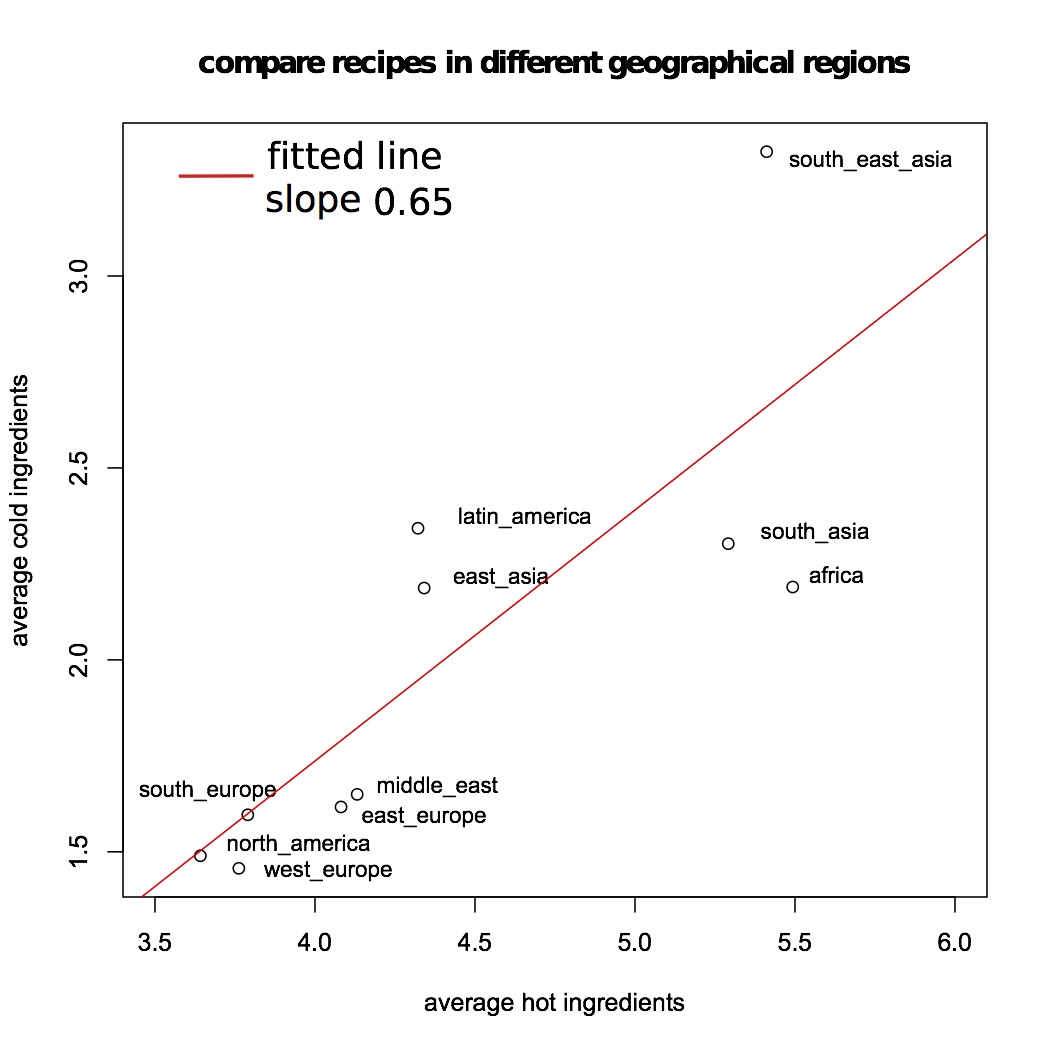

The figures show the similar relation between using number of hot and cold ingredients across different geographical regions. Now lets take an average of each plot and compare them together.

So what we have learned from this analysis; There is a difference in the number of ingredients across regions. In some regions food are simpler, consists of few amount of ingredients. That are points in the bottom left of the plot. Such regions are north America, Europe and Middle East. Whereas in Asian, African and Latin American cuisines number of ingredients per recipe on average is higher.

The Tahdig delicacy crust shaped around the rice in the form of a cake (Picture Source: YumSugar). There are in fact large varieties of the Tahdig.

There is a relationship between number of hot ingredients versus cold ingredients. Out of 10 ingredients in one recipes, the fraction of hot to cold ingredient is approximately 6.5 to 3.5. Why is that?

Of course there are limitations in this analysis that one needs to consider: the hot/cold categorization is based on Persian traditional food culture. Many ingredients are not listed. Many ingredients change their effect when they are cooked. Ingredients have different portion in one dish, here we ignore that. With more globalization, the culture of food is changing and maybe categorizing recipes based on geographical space is not 100% accurate.

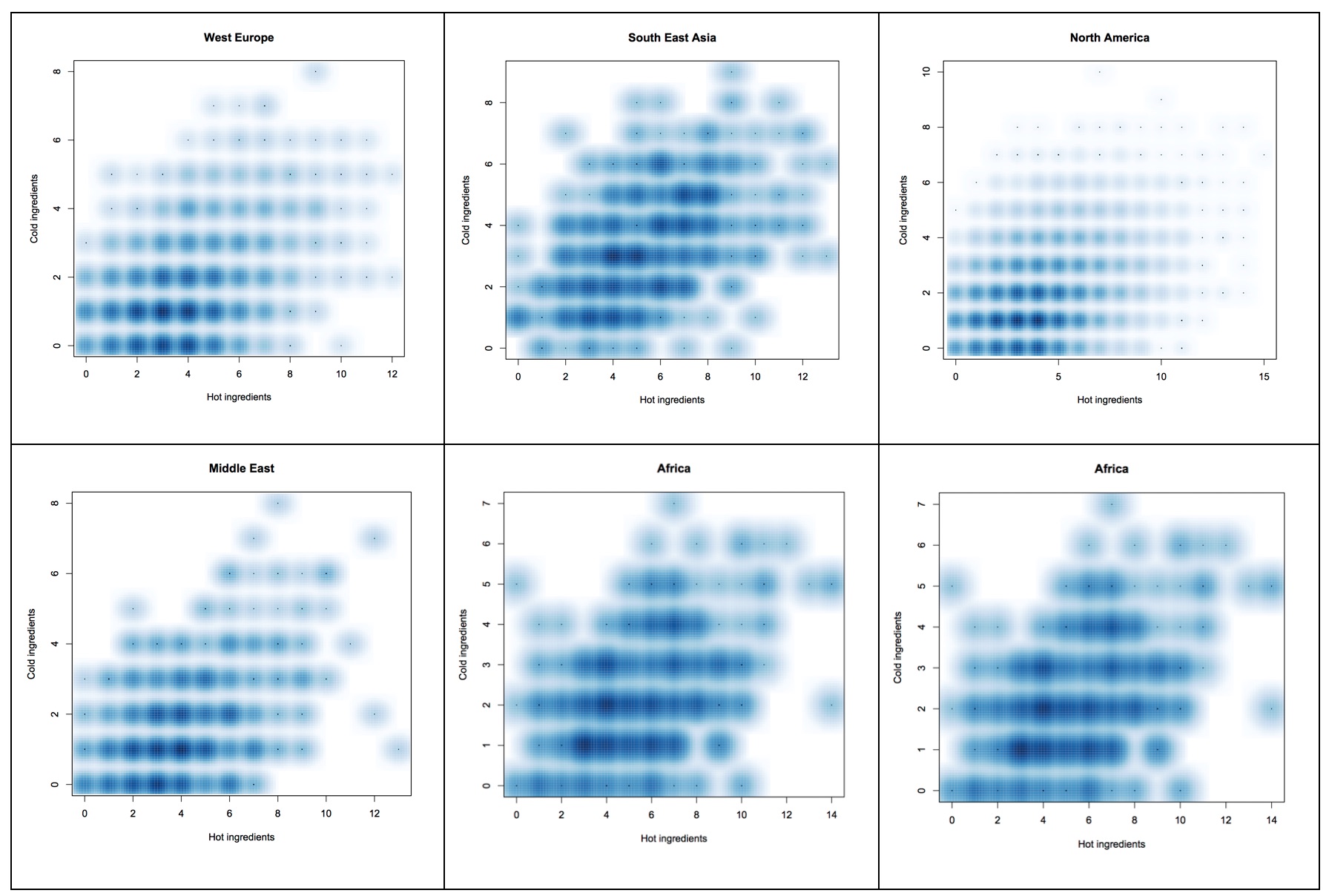

A comparison of recipes from different geographical regions as compiled by Fariba Karimi.

There are open questions here: What is the scientific reason behind the relationship between hot and cold ingredients? Is it related to the chemical reactions or temperature in different regions? Can this knowledge be used to diagnose some disease related to food or stomach ache? Can we use this knowledge to combine ingredients and come up with new recipes? Can we make recipes with right combination of ingredients to give us the best metabolism?