Below is a scholarly response published in Academia.edu entitled “The Decipherment of Linear Elamite Writing and a Curious Way of Doing Journalism: A Rejoinder to Andrew Lawler and the Smithsonian Magazine” to journalist Andrew Lawler, who recently published the article “Have Scholars Finally Deciphered a Mysterious Ancient Script?” a few days ago in the Smithsonian Magazine, the official journal of the Smithsonian Institute.

The scholarly response publication to the Andrew Lawler Smithsonian Magazine article has been penned by Gianni Marchesi also on behalf of Gian Pietro Basello, François Desset and Kambiz Tabibzadeh.

======================================================================================

An article published by Andrew Lawler a few days ago in the Smithsonian Magazine, the official journal of the Smithsonian Institute, bears an intriguing title: “Have Scholars Finally Deciphered a Mysterious Ancient Script?”

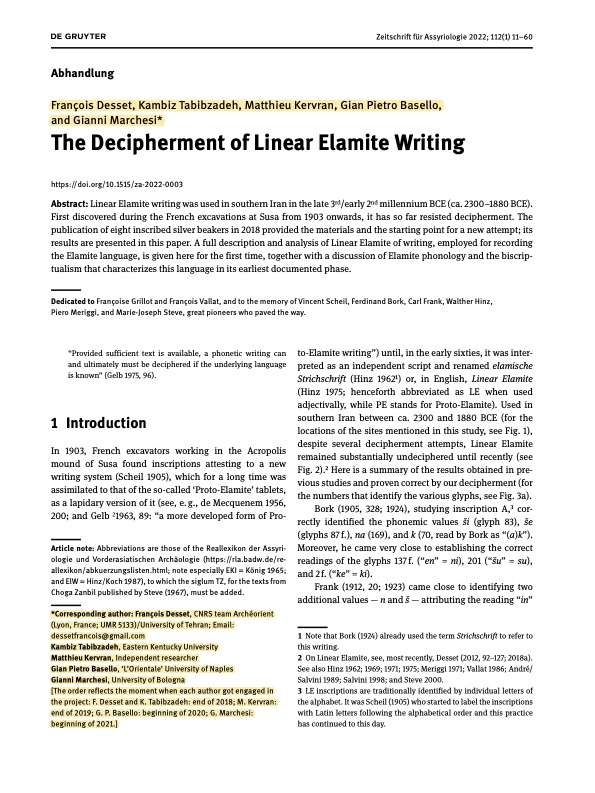

I, Gianni Marchesi (Associate Professor, Department of History and Cultures, University of Bologna – left image from University of Bologna), am one of five scholars who recently claimed to have deciphered Linear Elamite. When I started reading Lawler’s article, I quickly realized that it was focusing on an article of my colleagues and mine, which appeared in July in the last issue of the journal Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasitische Archäologie (henceforth ZA):

François Desset, Kambiz Tabibzadeh, Matthieu Kervran, Gian Pietro Basello, and Gianni Marchesi (2022). The Decipherment of Linear Elamite Writing. Zeitschrift für Assyriologie, volume 112, Number 1, pages 11–60.

NOTE By Kavehfarrokh.com: the above article has been cited as being among the “Best articles in Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies of 2022″ by the international scholarly De Gruyter venue … For more see: Decipherment of 4,400-year-old Iranian Linear Writing from Elam.

Andrew Lawler (at left- photo from his website, Andrewlawler.com) is a widely respected journalist. His website notes that “he has written more than a thousand newspaper and magazine articles from more than two dozen countries,” including The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, Smithsonian, and Science.

Andrew Lawler (at left- photo from his website, Andrewlawler.com) is a widely respected journalist. His website notes that “he has written more than a thousand newspaper and magazine articles from more than two dozen countries,” including The New York Times, The Washington Post, National Geographic, Smithsonian, and Science.

It was, thus, dismaying to read the following in his piece:

“If the findings are correct—and the claim is hotly debated by the researchers’ peers—…”

Which peers is he referring to? And what debate? As far as my co-authors and I are aware, our ZA paper—which underwent a double-blind peer review—has only received positive reactions.

Moreover, the incontrovertible facts and solid arguments presented in support of the decipherment are such that I would not expect there to be much disagreement about our conclusions. That said, the article in question has only just appeared and begun circulating in the scholarly community. It is too soon for it to have generated the kind of scholarly debate Lawler suggests it has.

It was additionally frustrating to note a major infelicity in Lawler’s article: the singling out of one of the authors of the ZA paper, François Desset (at left; associate researcher at CNRS Archaeorient from Lyon and specialist in the Bronze Age and the Neolithic in Iran), with no mention of his four co-authors. The paper we wrote was the product of our collective efforts. Lawler’s omission of this detail is mystifying. Journalists, no less than scholars, should be wedded to facts.

It was additionally frustrating to note a major infelicity in Lawler’s article: the singling out of one of the authors of the ZA paper, François Desset (at left; associate researcher at CNRS Archaeorient from Lyon and specialist in the Bronze Age and the Neolithic in Iran), with no mention of his four co-authors. The paper we wrote was the product of our collective efforts. Lawler’s omission of this detail is mystifying. Journalists, no less than scholars, should be wedded to facts.

Lawler’s article gives the false impression that François Desset was solely responsible for deciphering (or, for claiming to have deciphered) Linear Elamite, with the support of bit players, anonymous members of “a team of European scholars” under his direction (note, additionally, that Kambiz Tabibzadeh (at left; Eastern Kentucky University) is Iranian-American, not European) – for more see: “Decipherment of 4,400-year-old Iranian Linear Writing from Elam”…

Lawler’s article gives the false impression that François Desset was solely responsible for deciphering (or, for claiming to have deciphered) Linear Elamite, with the support of bit players, anonymous members of “a team of European scholars” under his direction (note, additionally, that Kambiz Tabibzadeh (at left; Eastern Kentucky University) is Iranian-American, not European) – for more see: “Decipherment of 4,400-year-old Iranian Linear Writing from Elam”…

What was Lawler’s purpose in obscuring the collaborative nature of our decipherment work? Was it to provide his readers with the romantic image of a modern-day Champollion (the decipherer of Egyptian hieroglyphics)? Was it to simplify the story, by focusing all criticism on just one member of our team?

The decipherment of Linear Elamite was only possible thanks to the combined efforts and talents of five scholars, but Lawler deprives readers of this crucial fact. Does he believe they are not able to track such details?

Elamite Silver cup (dated to the 3rd millennium BCE; housed in the National Museum of Iran) discovered in Marvdasht, Fars province (Source: Zereshk in Public Domain). The cup bears Linear-Elamite inscription which has been decoded by Desset, Tabibzadeh, Kervran, Basello, and Marchesi as follows: “For the Lady of Marapsha (toponym), (named) Shumar-asu, I made this silver vase. In the Temple that will be known by my name, Humshat, I dedicated it with goodwill for you.”

After reading Lawler’s article, the decipherment team wrote to him requesting appropriate revisions to his article, to which he responded:

“Smithsonian’s editorial policy is not to cite every author in a paper unless there are only one or two co-authors. This is a usual practice among all U.S. major publications, including Science, The New York Times, and the Washington Post.”

Brian Wolly, Digital Editorial Director of the Smithsonian Magazine, weighed in similarly: “This policy exists for readability and concision.”

This practice is reasonable in cases of research groups with specified team leaders or of papers with exceedingly large numbers of cited authors, such as papers on genetic studies, which can have hundreds of named authors. But neither is true in our case. As we suggested to Lawler, he could simply have referred to us, collectively, as “the authors” with no compromise to the readability or concision of his article. It is a fact of some importance that among the writers of our study there was no lead author (we were simply a group of scholars contributing equally to a group effort). What’s the use of the Smithsonian Magazine’s editorial policy if it obscures the truth? Lawler simply invented a lead author—Desset—with no concern for the ethics of accurate reporting.

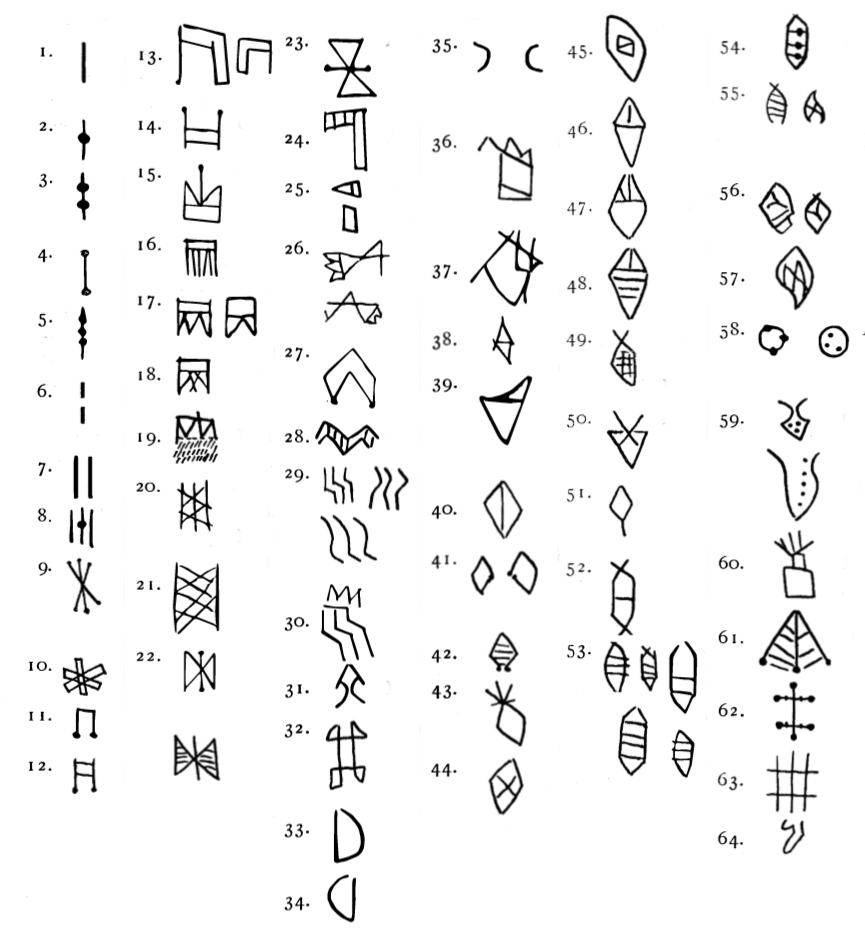

A list of known Linear Elamite characters prior to the publication in the Zeitschrift fur Assyriologie by François Desset, Kambiz Tabibzadeh, Matthieu Kervran, Gian Pietro Basello, and Gianni Marchesi (Source: Public Domain).

Journalists should be more attentive to the critical feedback of the persons they write about. In the case of the decipherment team, our sole interest is that our work is properly presented to the public. Journalistic license is, of course, permissible, but not when it results in a distortion of the facts.

Finally, for the benefit of the readers of Lawler’s article in the Smithsonian Magazine, it is worth pointing out a few additional minor inaccuracies:

1) “Part of the challenge is that the Elamite language—which may have been spoken in the region for more than 3,000 years—has no known relatives, making it difficult to know what sounds the symbols might represent. ‘The translations in some cases remain problematic,’ the authors acknowledge.”

Retort: Yes, “the translations in some cases remain problematic,” but not because of the difficulty of reconstructing the sounds of the symbols (to use Lawler’s terminology). In fact, the phonetic values of the vast majority of signs are well-established, albeit with some approximation, as is always the case for reconstructed ancient languages. It remains problematic because the grammar and the lexicon of the Elamite language are still imperfectly understood.

2) “But Desset argues that Linear Elamite takes an approach more like the modern alphabet. He concludes that the script draws solely on syllables, making it the oldest known writing system to do so.”

Retort: This is not correct. Linear Elamite is not a syllabic writing system; it is an alpha-syllabary. Linear Elamite signs represent syllables of the type CV (consonant plus vowel; e.g., /pa/) or have alphabetic values (e.g., /p/, /a/). Despite its alphabetic components, the Elamite writing system did not exploit this potential and never became a purely alphabetic script.

3) “Desset says his data strongly suggests that Proto-Elamite is a predecessor of Linear Elamite, as French experts first asserted in the early 20th century. That theory gets little support from scholars such as Oxford University’s Jacob Dahl and the University of Toronto’s Kathryn Kelley. They argue that Proto-Elamite is likely a mix of syllables and logograms and underscore the 800-year gap between the two writing systems.”

Retort: This way of presenting things is quite misleading: there is no contrast at all between what Desset says and what Dahl and Kelley (Dahl’s former pupil) argue. It is rather the journalist who has created such contrast. In fact, it is self-evident that the Linear Elamite signs derive from the older Proto-Elamite signs. It is equally self-evident that Proto-Elamite and Linear Elamite function differently (the latter, significantly, has no signs representing words—the so-called logograms). No one claims that they work in the same way. However, it is entirely plausible that the phonetic values we reconstruct for Linear Elamite signs were the same ones for their Proto-Elamite “ancestors.” If that does prove to be true, then scholars should be able to read those parts of the Proto-Elamite texts —if any—that were written phonetically.