Every few decades witnesses the arrival of a select few books on Iranian Studies that set the standard of academic excellent. The book, Arms & Armor from Iran: The Bronze Age to the End of the Qajar Period, by Dr. Manouchehr Mostagh Khorasani is not only in the tradition of the previous great scholars of Iranian Studies such as Roman Roman Ghirshman’s “Iran: Parthians and Sassanians” (1962), but also specifically sets the standard in the studies pertaining to the military history of Iran.

Every year, books published in countries other than Iran in various languages are reviewed and special plaques of Commemoration for Iranian Studies are awarded to the authors. The 16th Round of the World Prize for the Book of the Year of Iran was a lengthy and meticulous process. After the first selection of close to 2000 books in the different domains of Iranian and Islamic studies, 252 titles (78 titles in the field of Iranian Studies and 174 titles in the field of Islamic Studies) were selected for the second and final round of evaluations. The second round of evaluations was conducted by a panel of scholars from different universities in Iran and abroad.

The evaluation of works in two fields was conducted on the basis of preliminary appraisal of the works on the basis of published lists of books, discussions with academics, research and publication centers as well as information dissemination centers, participation in the most reputable international book exhibitions and counseling with instructors and distinguished experts in the fields of the Iranian Studies and Islamic studies both in Iran and abroad.

This resulted in the final selection of 13 winners for the World Prize of the Book of the Year of Iran. Dr. Manouchehr Moshtagh Khorasani was one of these distinguished awardees.

Some of the other distinguished world-class scholars who were awarded the prize were Dr. Nicholas Sims-Williams (SOAS), Dr. Elena E. Kuz`mina (Moscow State University). Dr. Christine van Ruymbeke (University of Cambridge), Dr. John Curtis and Dr. Nigel Tallis (The British Museum), Dr. Juan Martos Quesada (Universidad Compultense de Madrid) and Seyed Ahmad Khezri (Iranian cultural attaché in Madrid), Dr. Mohsen Zakeri (Universität Frankfurt), Dr. István Nyitral (Budapest University), Dr. Peter Avery (University of Cambridge), Dr. Beate Dignas (Sommerville College) and Dr. Engelbert Winter (Westfälische Wilhems-Universität Münster), Dr. Walli Ahmadi (University of California, Berkeley), Dr. Asad Abdolhadi Ghandil (University of Cairo), Dr. Benjamin Jokisch (Albert-Ludwig-Universität Freiburg), and Dr. Robert Gleave (University of Exeter).

Having taken more than 10 years of meticulous research and field studies to complete, Dr. Khorasani’s book produces information never seen in western historiography and references. The book contains 2500 color photos of weapons never before seen in western or international museums or academic venues. At the very least, the book will help dispel a number of misconceptions with respect to ancient Iranian militaria.

The book however is as much about the evolution of Iranian metallurgy and art history as it is about militaria. Khorasani’s book carefully analyzes the development of Iranian metalwork technology and related developments with respect to arms and armor dating from the Bronze Age to the Qajar era. Khorasani expostulates upon the symbiotic nature of the technological relationship between regions such as Lursitan and Marlik.

Spearhead from ancient Amarlu. Note the resilience of the metalwork after thousands of years; especially the “swirls” applied at the shaft (Copyright 2006).

Khorasanis’ text is indeed a breakthrough in terms of the history of the metallic arts of Iran; one example being Zoroastrian (and pre-Zoroastrian) mythological motifs. It was during the early Iranic arrivals and the Mede era where much of the basis of the “Persepolis Arts” was first laid. These were ancient Iranian mythological motifs and were impressed upon the metal works of ancient locales such as Luristan. Examples include bird-beasts appearing on metal works such as daggers and swords.

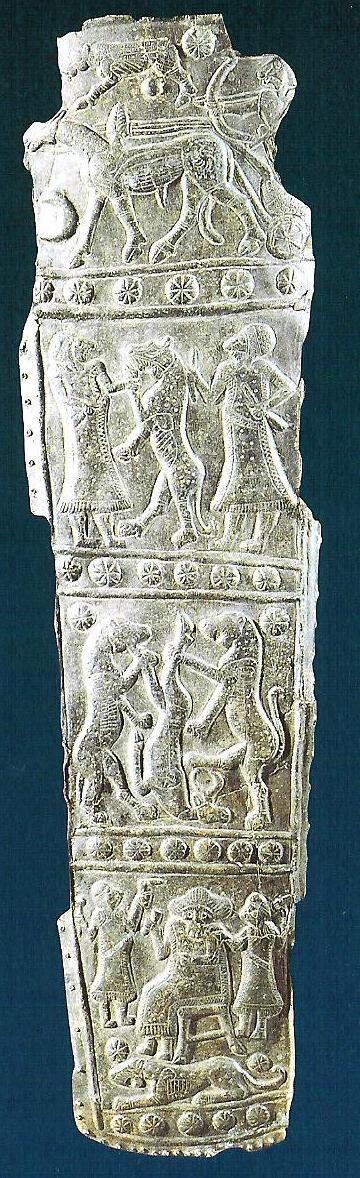

Quiver Plaque from ancient Luristan. Many of the motifs seen (i.e. king seated on throne) were to appear in various forms in later Medo-Achaemenid arts, especially at Persepolis (Copyright 2006).

These motifs were to exert a profound influence on later European and Far eastern arts, especially due to the Scythian/Saka contacts in Central Asia, the Caucasus and Europe. The motif of the Akenakes dagger for example could be seen in later Alanic warriors migrated into Western Europe by the 4th century AD.

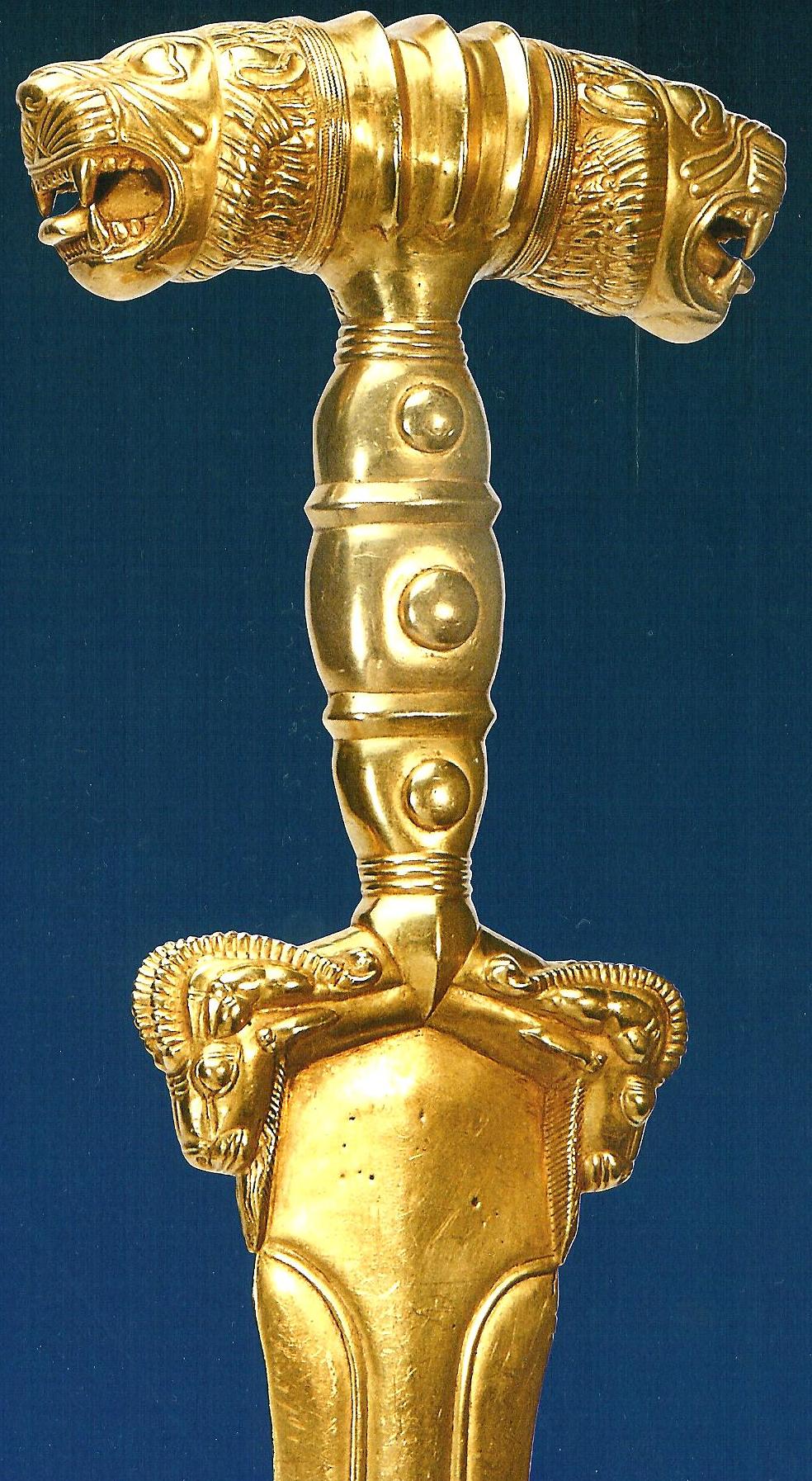

Achaemenid Achenakes. Note the lion and ram motifs, both symbols of ancient Iran (Copyright 2006).

The technological developments in Persia continued to proceed even after the fall of Achaemenid Persia to Alexander the Great. Khorasani outlines the continuation of Iranian technological developments in the framework of blade weapons (swords and daggers), archery equipment, lances, spears, javelins, helmets and armor. These are in tandem with the development of the metallic arts of Iran. This is significant as Khorasani is perhaps the first researcher to comprehensively examine such developments in the domain of military technology.

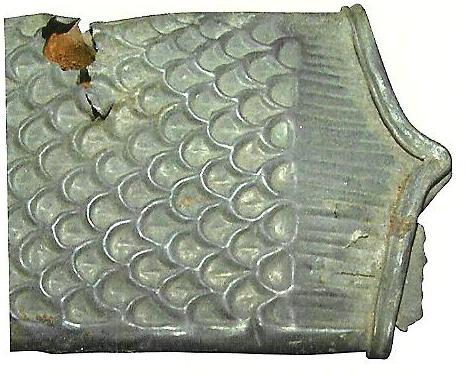

Portion of the sheath of a late Sassanian sword (late 6th to early 7th century AD) (Copyright 2006).

Iranian metalwork technology continued to evolve during the post-Islamic period, and experienced a powerful renaissance during the Safavid era (1501-1736).

Sword sheath attributed to Shah Abbas (r. 1588 – 1629). Note the fine craftsmanship on the sheath (Copyright 2006)

The pre-Islamic “Spangenhelm” helmets of riveted construction metallic plates, reached a very high level of sophistication during the Sassanian era. Metallurgy, helmet design and corresponding arts were to evolve into more advanced designs that were to appear during the post-Islamic Iran.

Helmet of the Safavid era (1501-1722). Among the motifs are grape patterns also seen in the national arts of Georgia (Copyright 2006).

Other never seen items are articles from the Afsharid (r. 1736-1747) and Zand (1750-1794) periods.

Sword of Nader Shah (1688-1747) (Copyright 2006).

Bazu-band from the Zand era (Copyright 2006).

Khorasani also demonstrates that some of the highest quality metal works (notably in swords and shields) were constructed during the Qajar period (1781-1925). This information is virtually unknown in western historiography which remains primarily focused on the defeats of the Qajars at the hands of imperial Russian forces who invaded Iranian territory in the Caucasus and Central Asia during the 18th and 19th centuries.

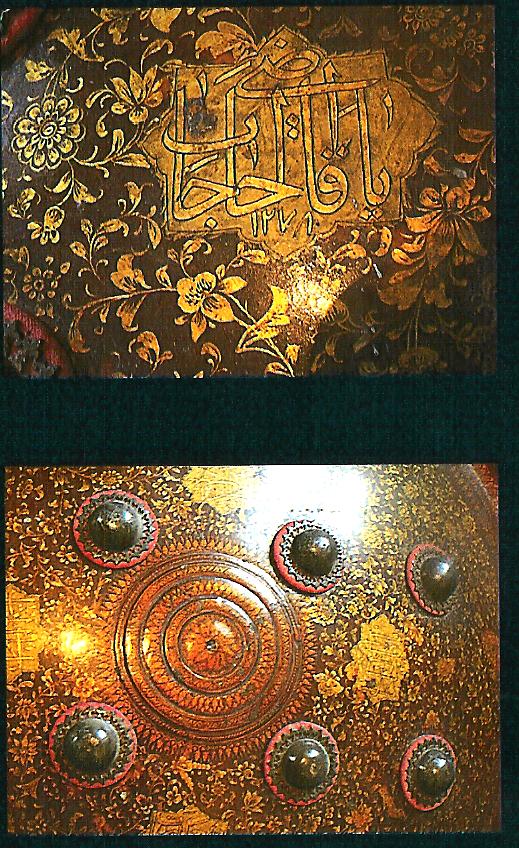

Khanjar from the Qajar era. Note the application of color motifs not unlike those seen in the Sassanian era (Copyright 2006).

Shield attributed to Nasser e Din Shah (1831-1896). Note the flowing artistry techniques which can be traced as far back as the pre-Islamic Sassanian era (Copyright 2006).

====================================================================

Dr. Kaveh Farrokh

- Member of Stanford University’s WAIS (World Association of International Studies)

- Advisor of Iranian Studies for Hellenic-Iranian Studies at Leiden University

- Historical Advisor for the History Channel

- Historical and Archaeological Advisor for the Voice of America media network

- Historical Advisor to a film project titled In Search of Cyrus the Great

- Academic Advisor for the Persian-American Society

- Director of the Archaeological department of the Pasargad Preservation Foundation

- Advisory Committee Member of the Dabiri Foundation

- Member of the Iranian-Canadian Congress

- Member of Persian Gulf Preservation Society

- Member of Iran Linguistics Society

- Winner of London’s WAALM Best History Book of 2008 Award

- Citation by US Independent Book Publisher’s Association in 2008