The version printed has been slightly edited. Kindly note that excepting one image, all other images and accompanying captions do not appear in the original War History Online publication. readers are also encouraged to consult the following article (available for download in Academia.com):

For readers further interested in the military history of ancient Iran, consult:

- Military History and Armies of the Scythians and Sarmatians

- Military History and Armies of the Achaemenids

- Military History and Armies of the Parthians

- Military History and Armies of the Sassanians

====================================================================================

In an era before dog tags or modern military bureaucracy, ancient and medieval powers needed to get creative in how they kept track of their military might.

One of the bleakest aspects of war is the death toll. Young men, torn from their families in the name of their country, sacrifice everything in their service to a higher calling. One of the greatest challenges nations face after a battle is counting and naming the dead. Up until the nineteenth century identifying those who gave everything for their country loomed as a nearly impossible task. One ancient civilization found a solution at least to the problem of counting the dead.

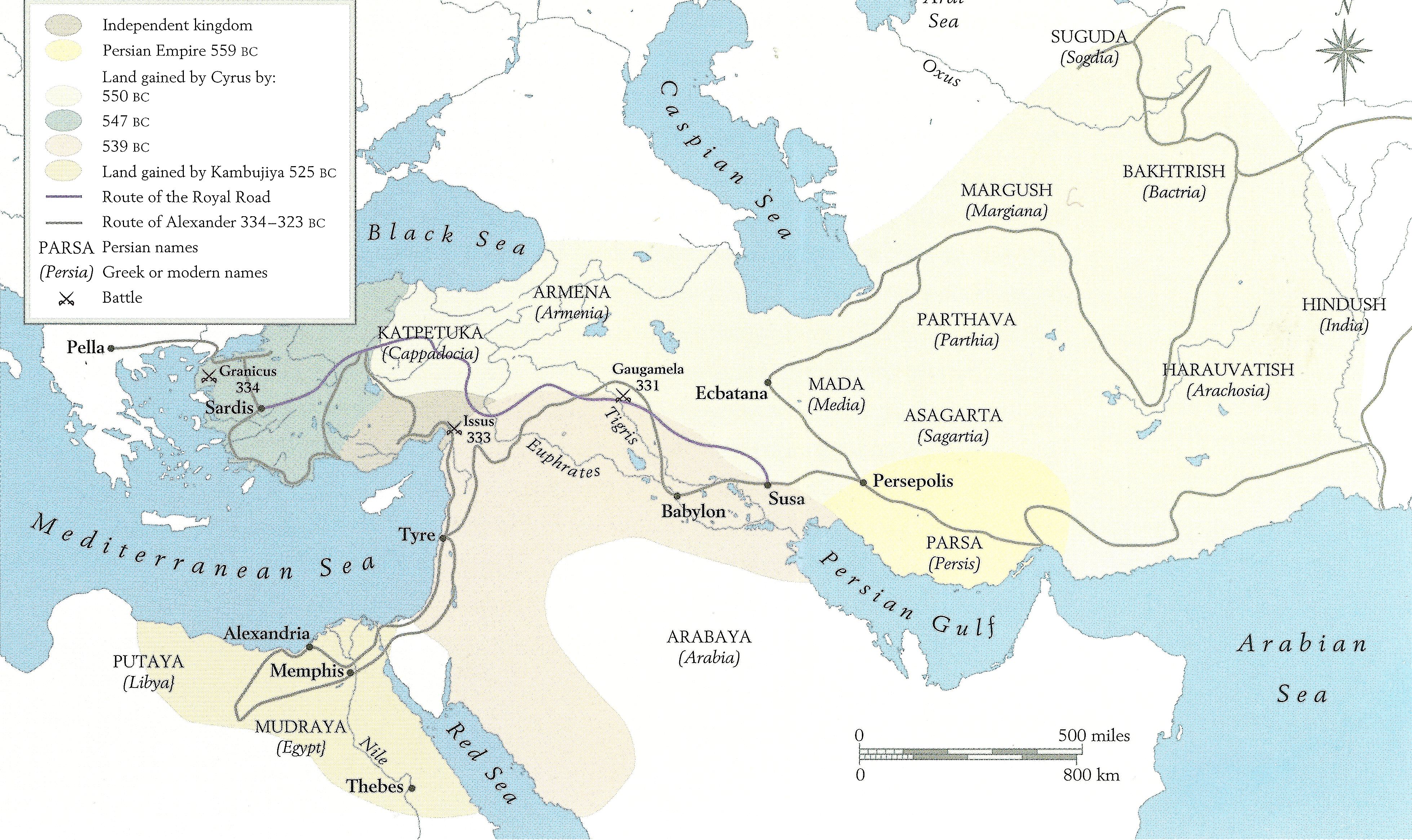

For much of ancient and early western civilization, the Persian Empire loomed as the largest, most powerful empire. At its height, stretching from the fringes of India to Anatolia, the mighty empire proved a grave concern for any rival empires or civilizations in the region.

The Greek city-states kept wary eyes upon the massive Achaemenid Empire, which would fall and then reorganize itself following the conquests and deaths of Alexander the Great.

Map of the Achaemenid Empire (Farrokh, 2007, page 87, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا-:

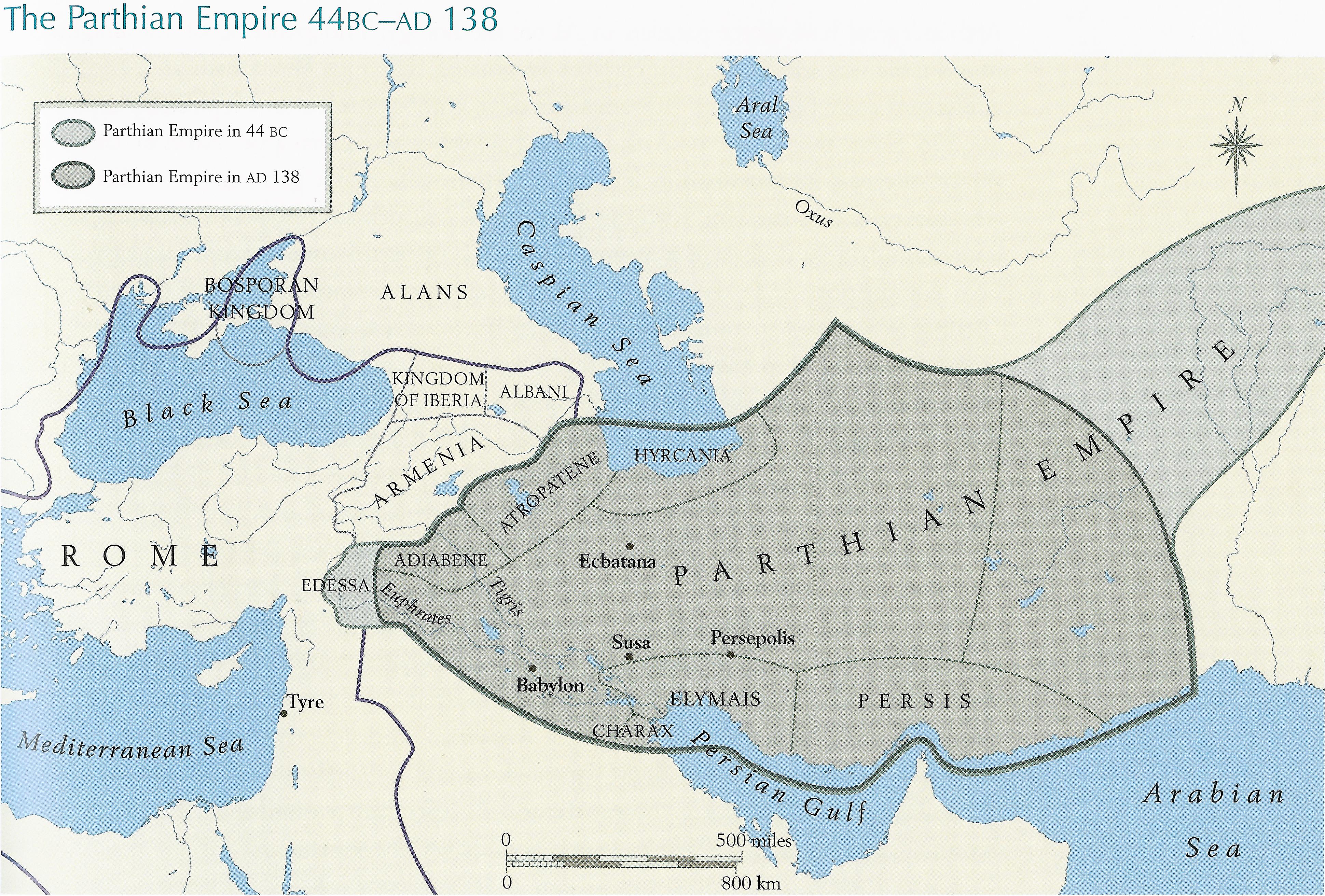

Its replacement, the Seleucid Empire, and later the Parthian and Sassanid Empires, stood as perpetual thorns in the side of the Roman Empire as it struggled to control the eastern borders of its massive empire. The Byzantine Empire fared little better against the Sassanids.

Regardless of its incarnation, each empire stood as a massive, sprawling entity composed of many tribes, cultures, and peoples. The armies these empires brought to war were stated by ancient historians to be in the millions. Though almost certainly an exaggeration, the various Persian empires could easily muster hundreds of thousands of soldiers. Keeping an accurate count of their soldiers would be a staggeringly difficult proposition for an ancient civilization.

Map of the Parthian Empire in 44 BCE to 138 CE (Farrokh, page 155, Shadows in the Desert: Ancient Persia at War-Персы: Армия великих царей-سایههای صحرا–).

In an era before dog tags or modern military bureaucracy, ancient and medieval powers needed to get creative in how they kept track of their military might. By the sixth century, the Sassanids developed a method to keep track of how many soldiers died during a campaign. The writings of Procopius, who extensively covered the campaigns of Byzantine emperor Justinian I, explained their method. According to the Greek historian:

“It is a custom among the Persians that when they are about to march against any of their foes the king sits on the royal throne and many baskets are set there before him. The general also is present who is expected to lead the army against the enemy, and the army passes along before the king, one man at a time, and each of them throws one arrow into the baskets. After this they are sealed with the king’s seal and placed in a secure location.”

A plate of Sassanian Emperor Khosrow I Anoushirwan (Immortal Soul) (r. 531-579 CE) housed in the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris, France (Source: History of Iran in Public Domain).

Once the campaign concluded, the men returned to retrieve their arrows. As Procopius explained:

“Those whose office it is to do so count all the arrows that have not been taken by the men, and they report to the king the number of soldiers who have not returned, and in this way it becomes evident how many perished in the war.”

Thought undoubtedly time consuming, the ingenious method allowed the Persian king to do what few other civilizations could do, and keep an accurate count of his soldiers.

Persian warriors in line (Source: War History On-Line).

The Persians’ ability to do so gave them an invaluable advantage against their foes, even one as sophisticated as the Byzantines. Though it failed to reveal exactly who had died in the campaign, the arrow method allowed the Persians to at least keep track of their army’s numbers before and after a campaign.

This not only allowed for wider strategic thought, but it also revealed commander effectiveness. In Procopius’ writings, a Persian commander was rebuked for the number of arrows remaining after a failed siege of a Roman fortress.

Detail of Byzantine Historian, Procopius of Caesarea (c.500-c.570 CE) (Source: James Michael Gilmer Procopius of Caesarea: A Case Study in Imperial Criticism) [Cardiff University],

Even as the Middle Ages dawned and feudal lords replaced the emperors of Rome, few leaders could accurately keep track of their manpower. The arrow method illustrates how ancient commanders used whatever they could to keep track of success and failure on the battlefield.